Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

02: What Are Metacognitive Feelings?

[email protected]

Crude Picture of the Mind

- epistemic

(knowledge states) - broadly motoric

(motor representations of outcomes and affordances) - broadly perceptual

(visual, tactual, ... representations; object indexes ...)

feelings of knowing/not knowing (Koriat 1995, 2000)

tip-of-the-tongue experiences (Brown 2000; Schwarz 2002)

feelings of certainty/uncertainty (Smith et al. 2003)

feelings of confidence (Winman and Juslin 2005)

feelings of ease of learning (Koriat 1997)

feelings of competence (Bjork and Bjork 1992)

feelings of familiarity (Whittlesea et al. 2001a, 2001b)

feelings of ‘déjà vu’ (Brown 2003)

feelings of rationality/irrationality (James 1879).

feelings of rightness (Thomson 2008)

Dokic 2012, p. 302

feeling of surprise

‘the intensity of felt surprise is [...] influenced by [...]

the degree of the event’s interference with ongoing mental activity’

Reisenzein et al, 2000 p. 271; cf. Touroutoglou & Efklides, 2010

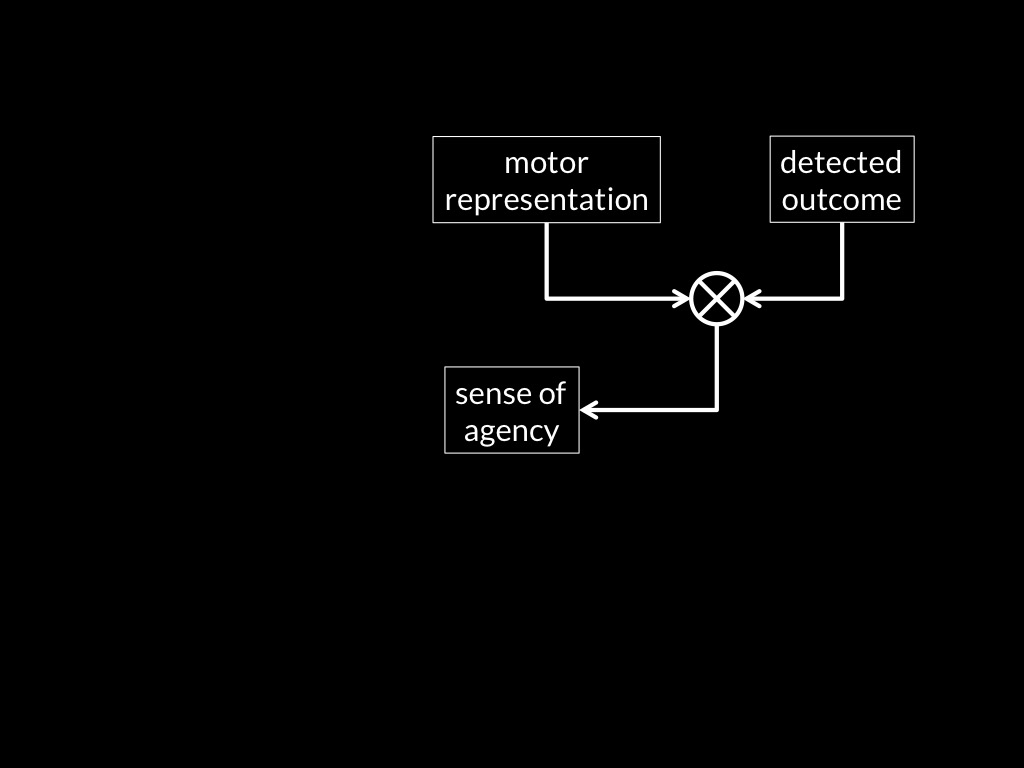

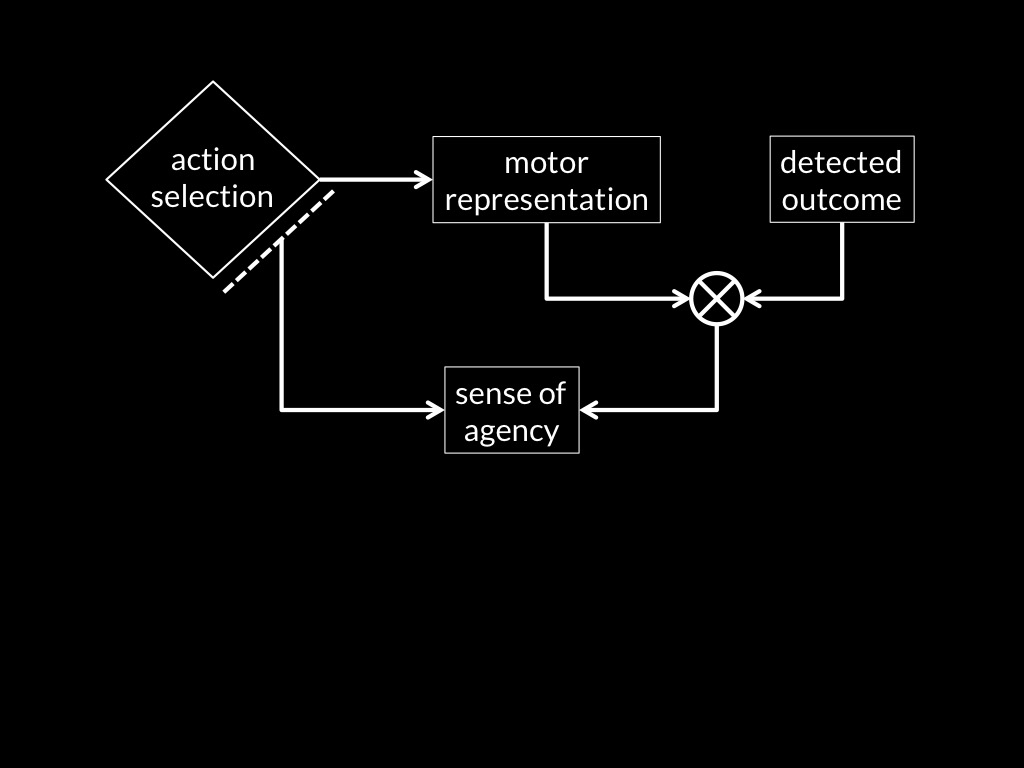

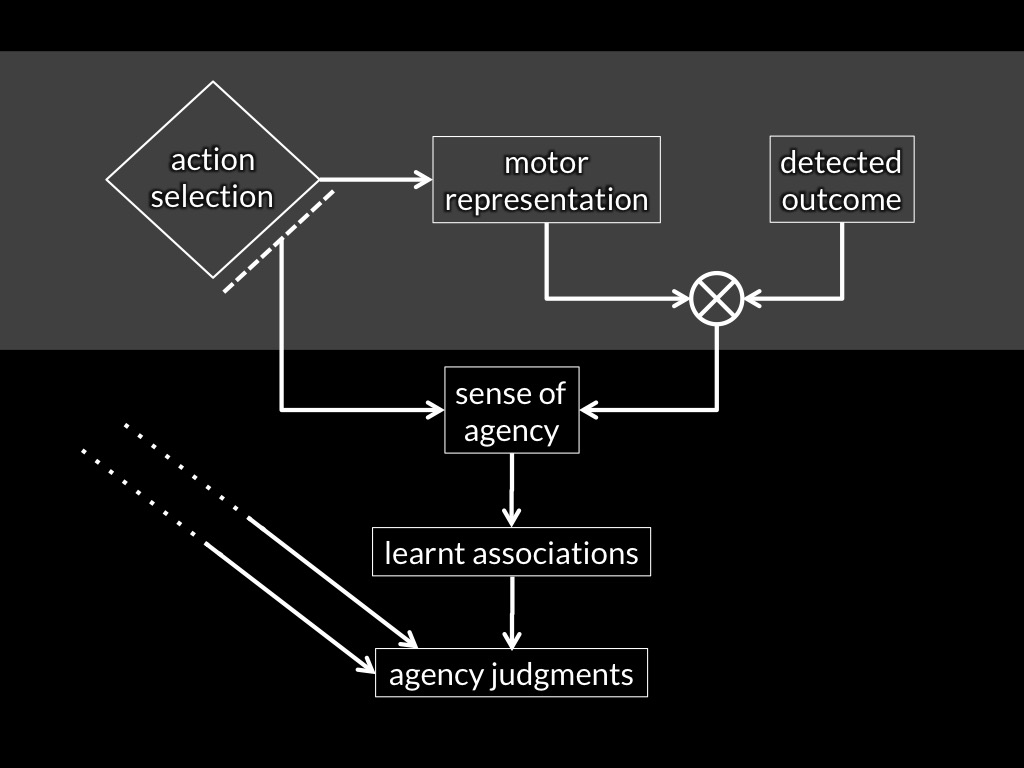

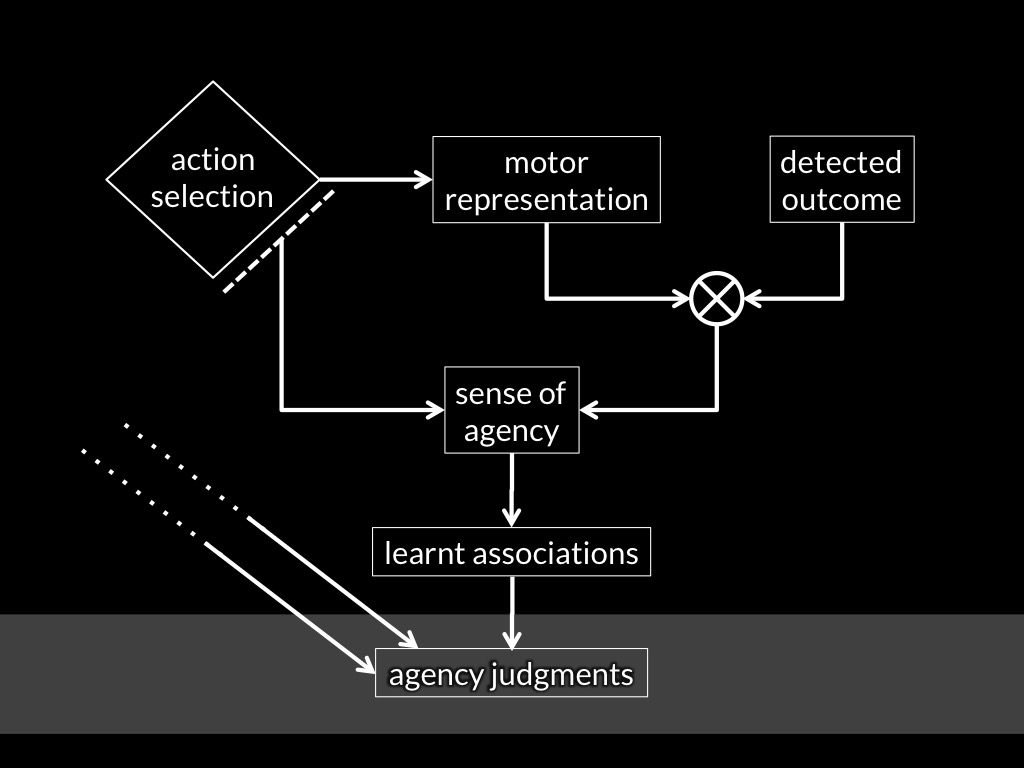

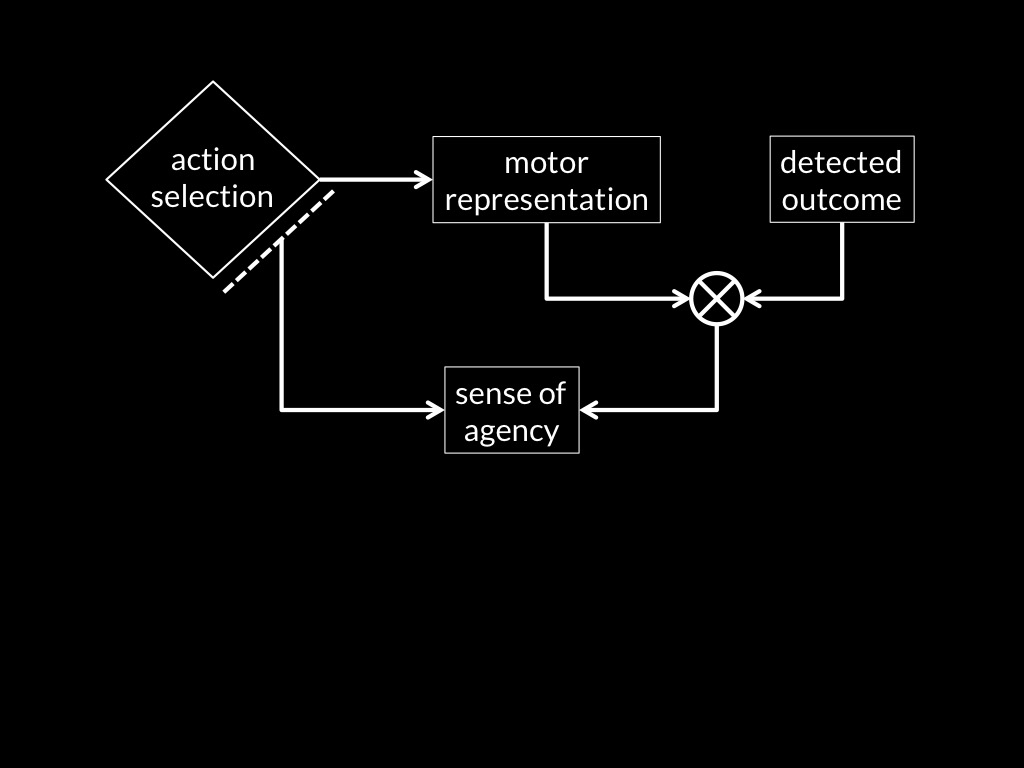

Adapted from Sidarus & Haggard, 2016 figure 5

Adapted from Sidarus & Haggard, 2016 figure 5

But what are metacognitive feelings?

Metacognitive feelings

There are aspects of the overall phenomenal character of experiences which their subjects take to be informative about things that are only distantly related (if at all) to the things that those experiences intentionally relate the subject to.

Metacognitive feelings

can be thought of as

sensations.

Sensations are

- monadic properties of perceptual experiences

- individuated by their normal causes

- (so they do not involve an intentional relation)

- which alter the overall phenomenal character of those experiences

- in ways not determined by the experiences’ contents.

Sensations can trigger beliefs via associations.

metacognitive feelings

Thereare aspects of the overall phenomenal character of experiences which their subjects take to be informative about things that are only distantly related (if at all) to the things that those experiences intentionally relate the subject to.

consequences & questions

Crude Picture of the Mind

- epistemic

(knowledge states) - broadly motoric

(motor representations of outcomes and affordances) - broadly perceptual

(visual, tactual, ... representations; object indexes ...) - metacognitive feelingsmetacognitive feelings

Q1

Are metacognitive feelings sensations in Reid’s sense?

Q2

Can we also think about categorical peception of colour on this model?

Q3

Why do humans have metacognitive feelings?

Dokic’s ‘Water Diviner’ model:

‘noetic [metacognitive] feelings ... are first-order bodily experiences, namely non-sensory affective experiences about bodily states, which given our brain architecture co-vary with first-order epistemic states, in such a way that they can be recruited, through some kind of learning or association process, to represent conditions hinging on relevant epistemic properties of one’s own mind.’

Q1

Are metacognitive feelings sensations in Reid’s sense?

Q2

Can we also think about categorical peception of colour on this model?

Q3

Why do humans have metacognitive feelings?

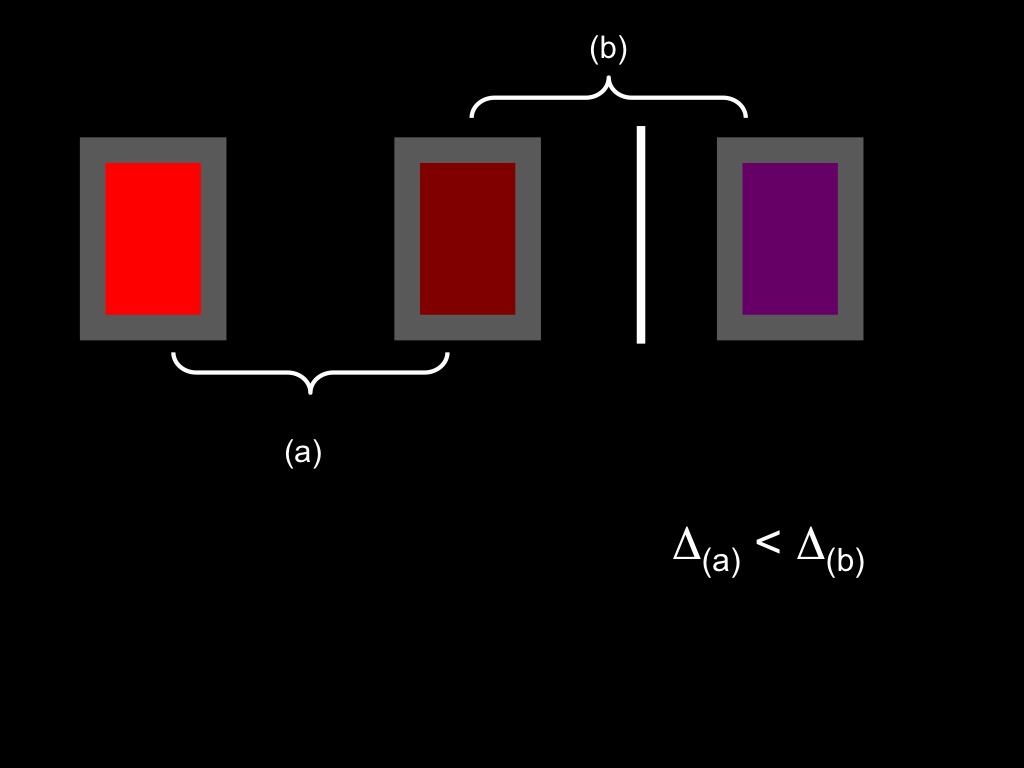

1. The second sequence of sensory encounters, (b), differ from each other more in phenomenal character than the first sequence of sensory encounters, (a), differ from each other.

2. This difference in differences in phenomenal character is a fact in need of explanation.

3. The difference cannot be fully explained by appeal only to perceptual experiences as of particular shades.

4. The difference can be explained in terms of perceptual experiences as of categorical colour properties.

5. There is no better explanation of the difference.

Q1

Are metacognitive feelings sensations in Reid’s sense?

Q2

Can we also think about categorical peception of colour on this model?

Q3

Why do humans have metacognitive feelings?

‘metacognitive feelings ... allow a transition from the implicit-automatic mode to the explicit-controlled mode of operation.’

Koriat, 2000 p. 150

Adapted from Sidarus & Haggard, 2016 figure 5

Q1

Are metacognitive feelings sensations in Reid’s sense?

Q2

Can we also think about categorical peception of colour on this model?

Q3

Why do humans have metacognitive feelings?