Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Question 3: Automaticity

Q1

How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing models?

Q2

Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

Q3

Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes but not always automatic? How could belief-tracking be automatic given evidence that it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?

belief-tracking is sometimes but not always automatic

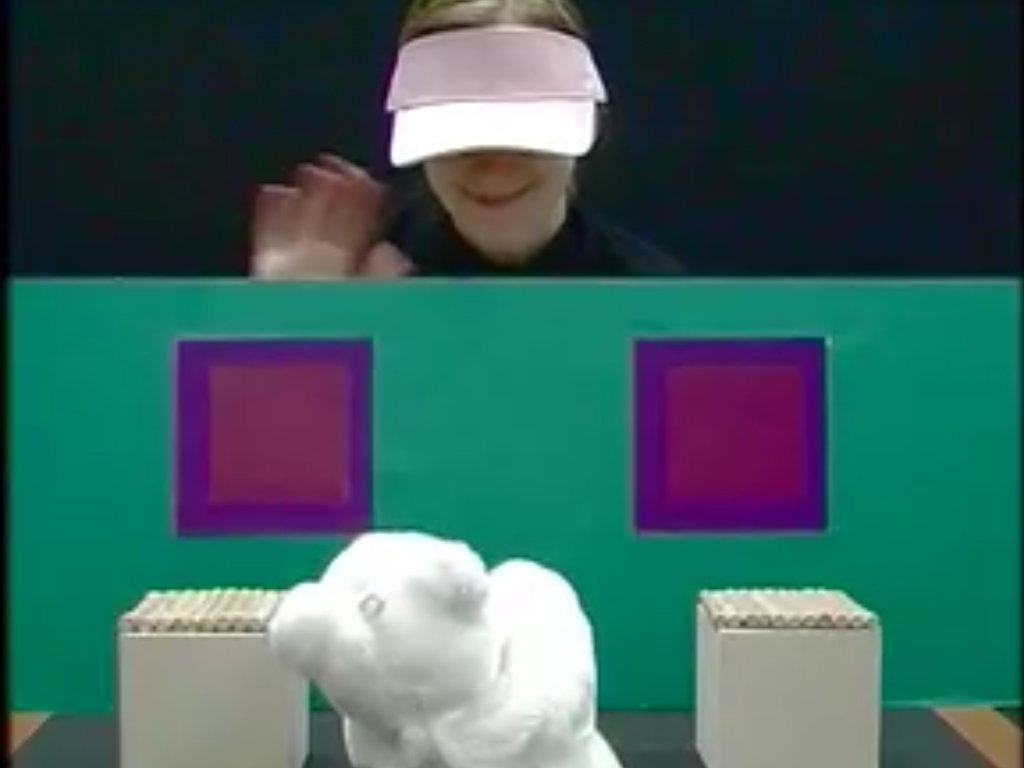

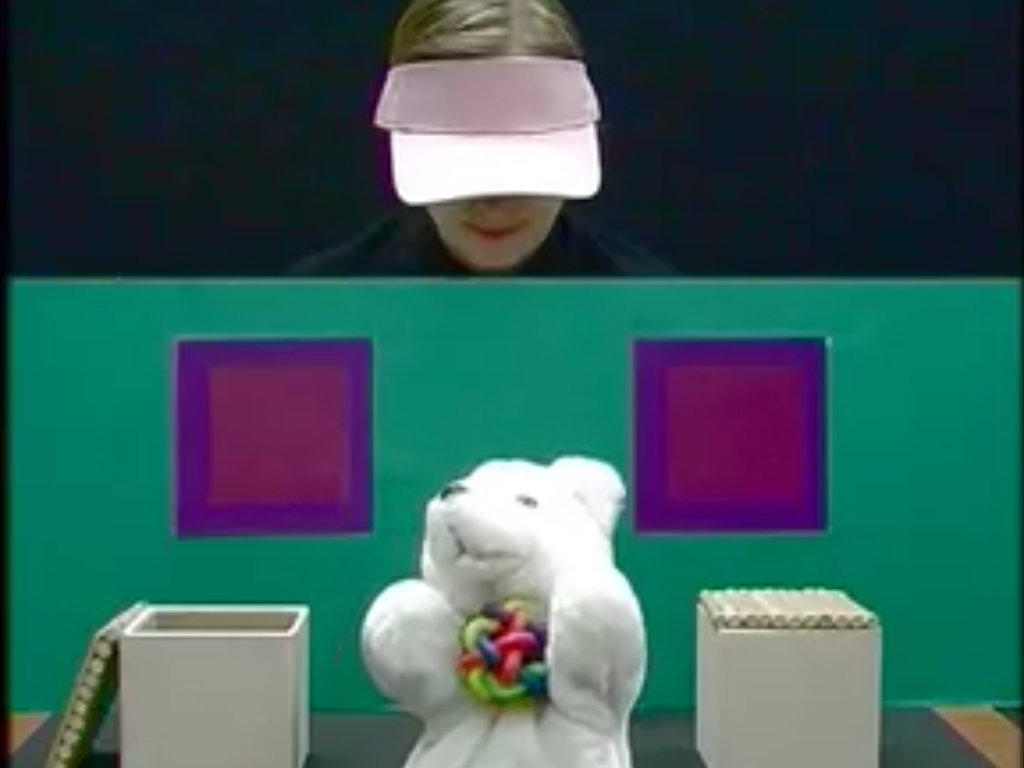

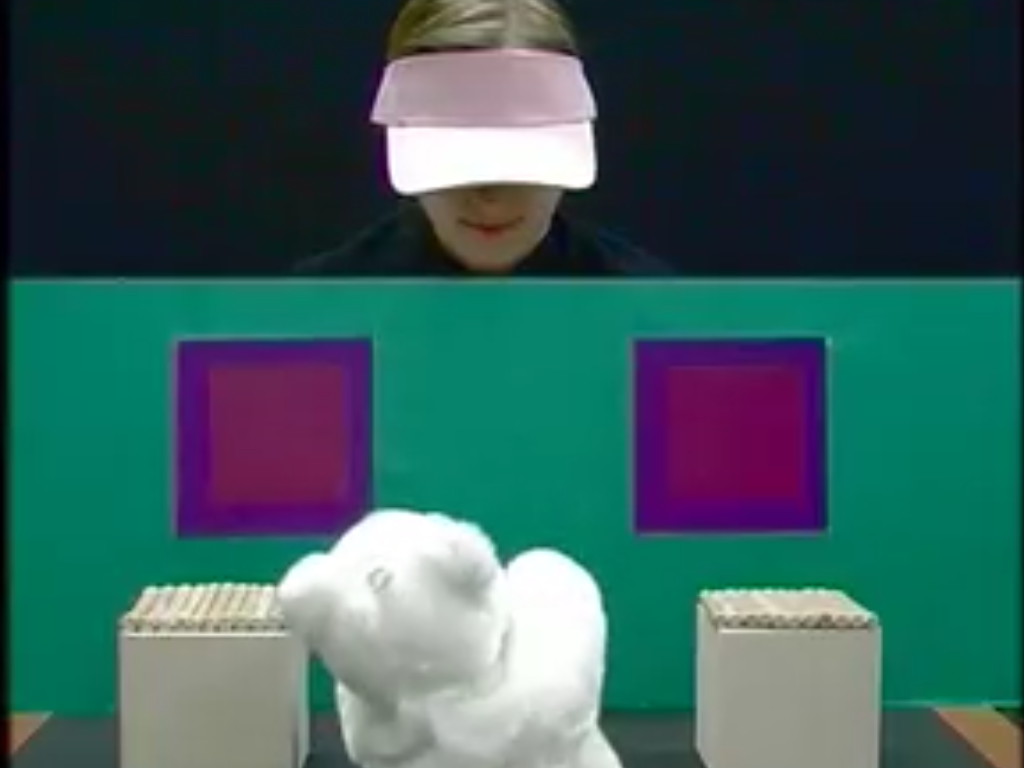

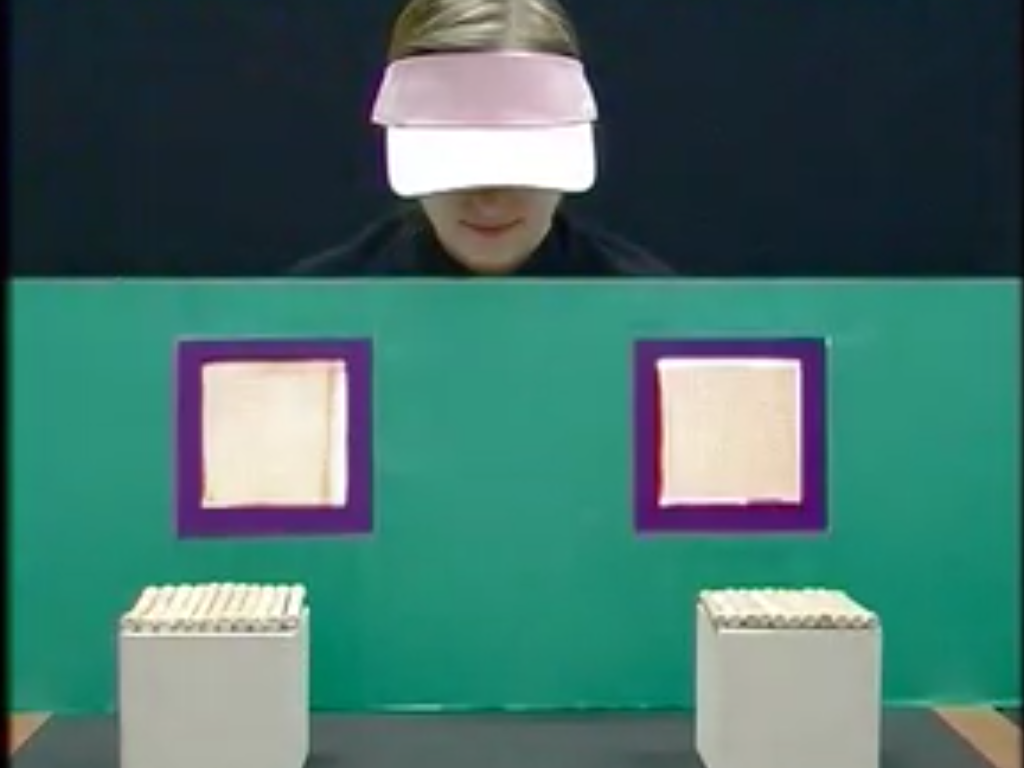

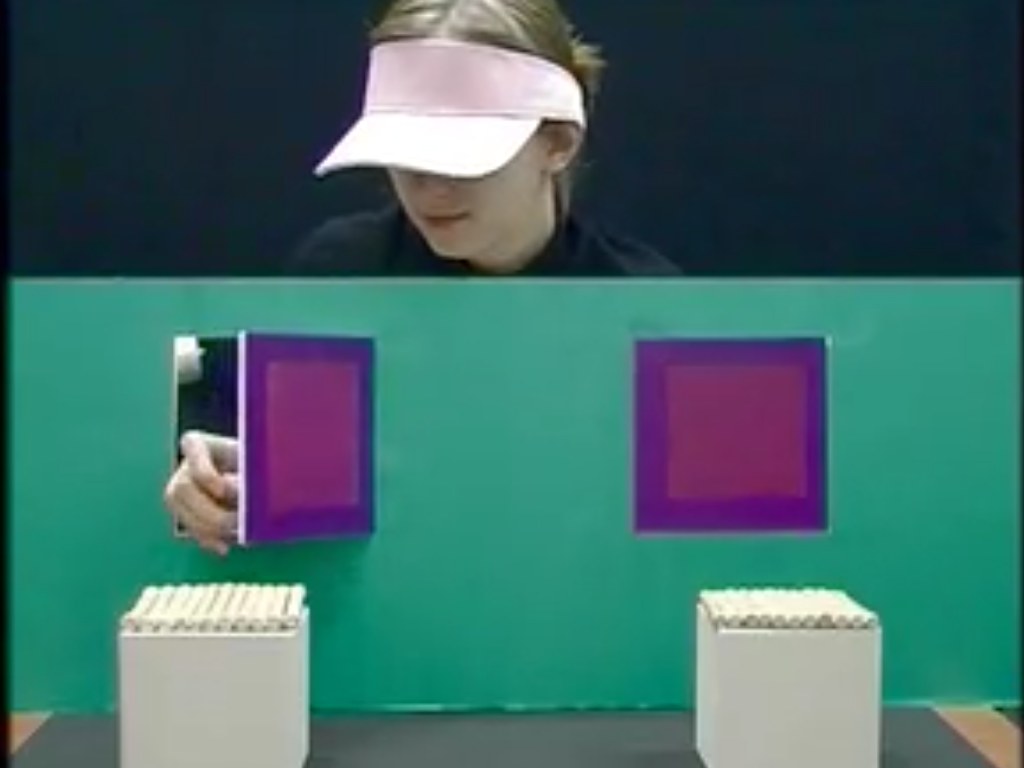

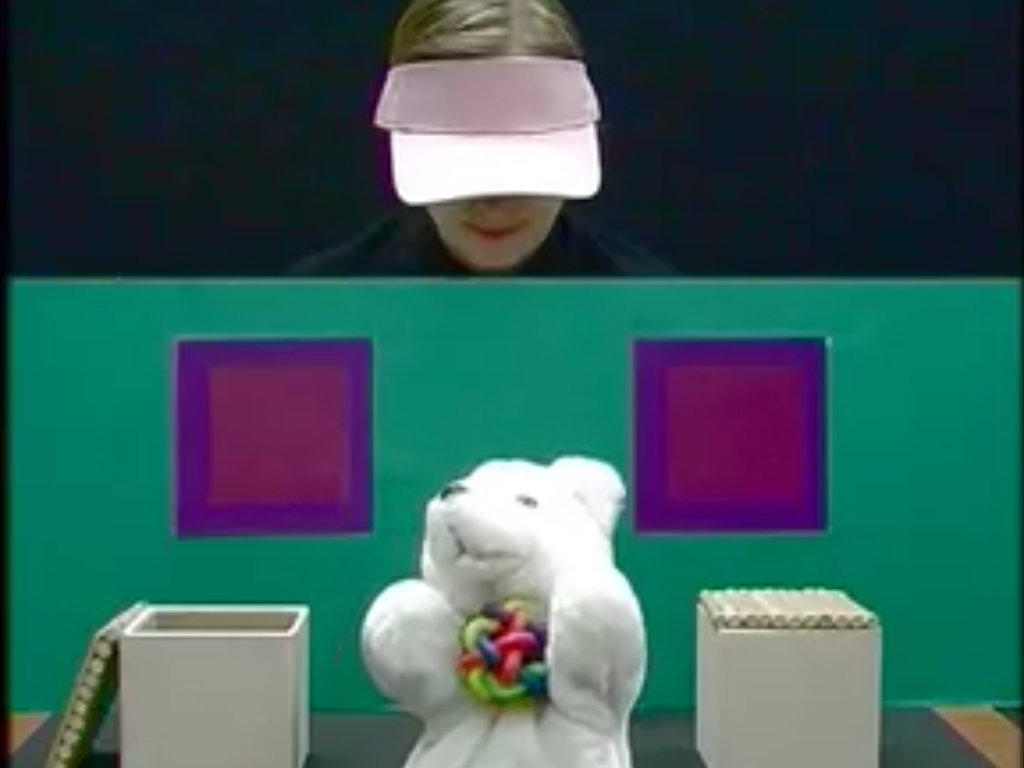

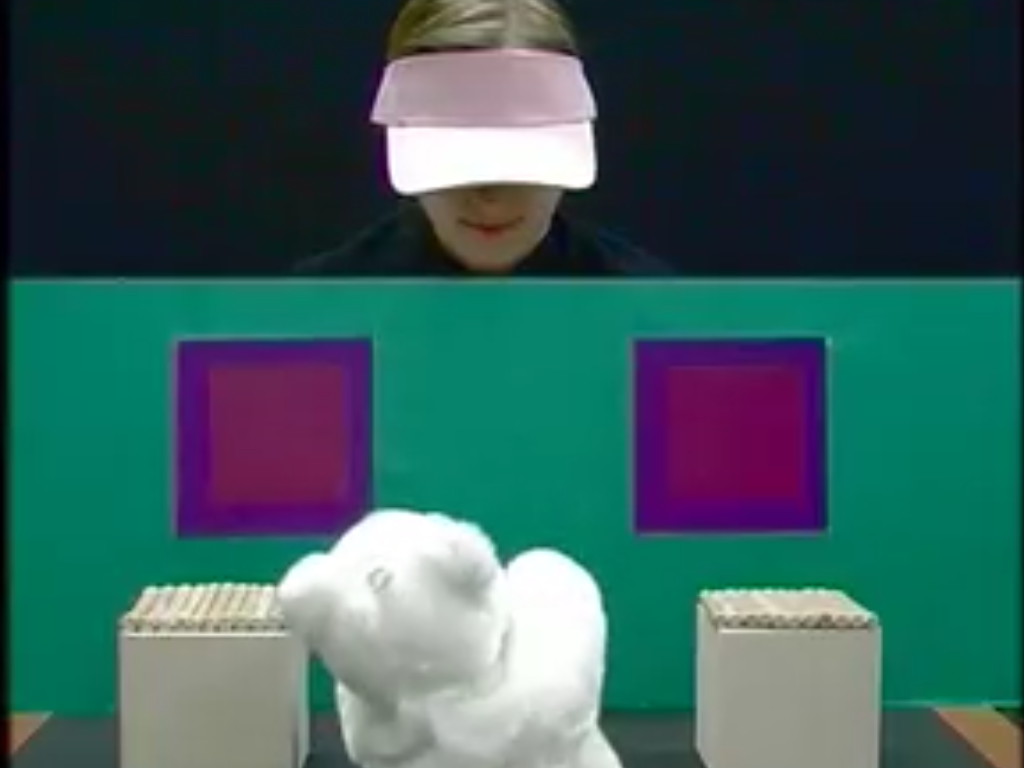

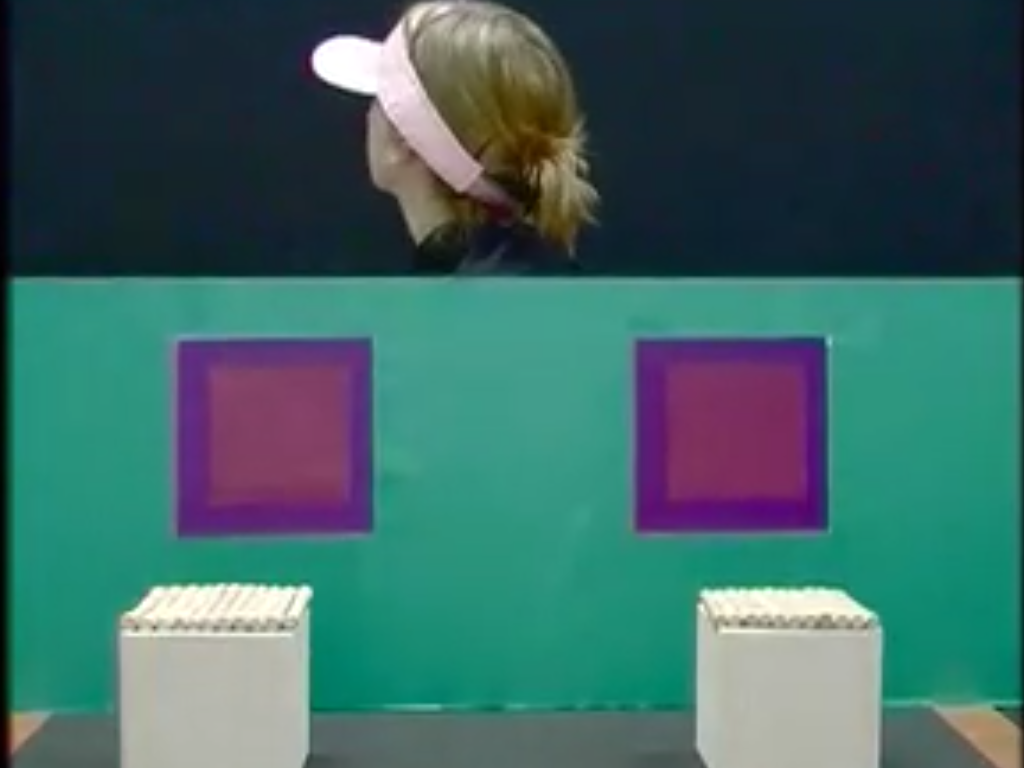

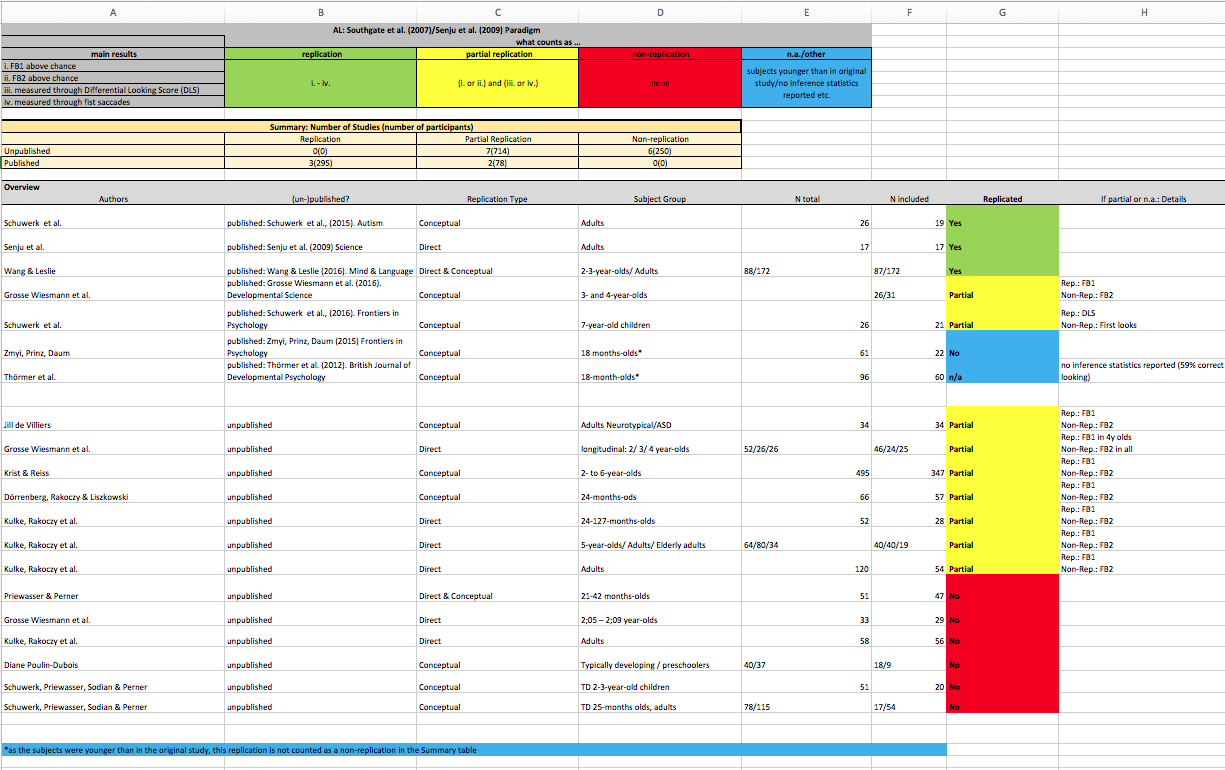

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

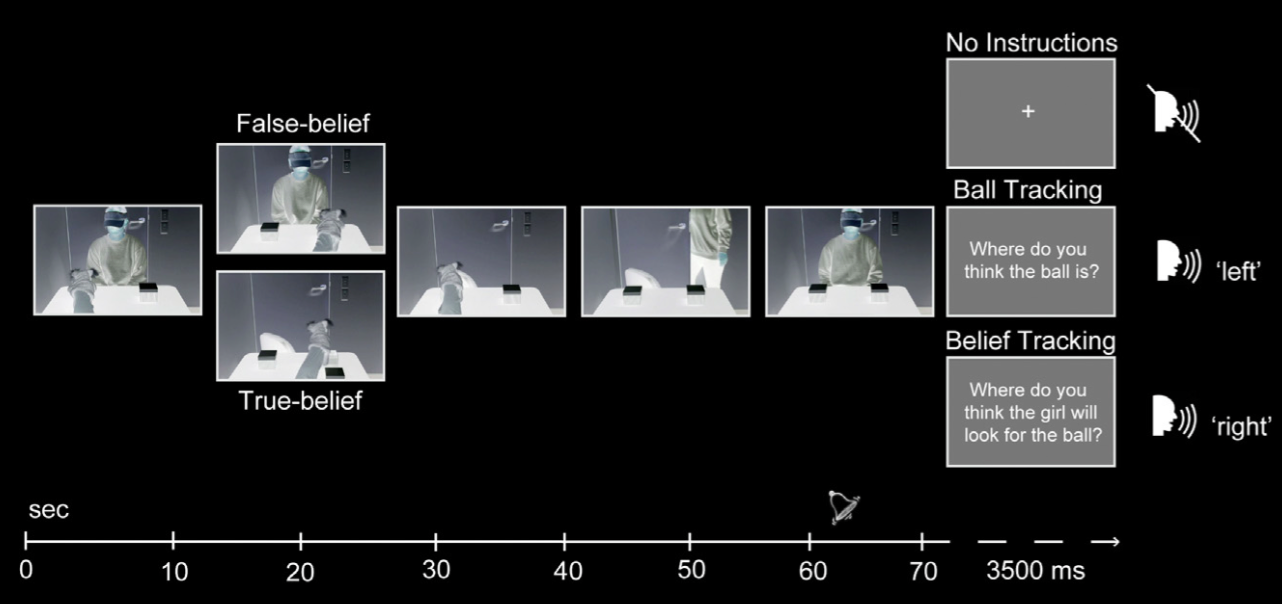

Schneider et al (2014, figure 1)

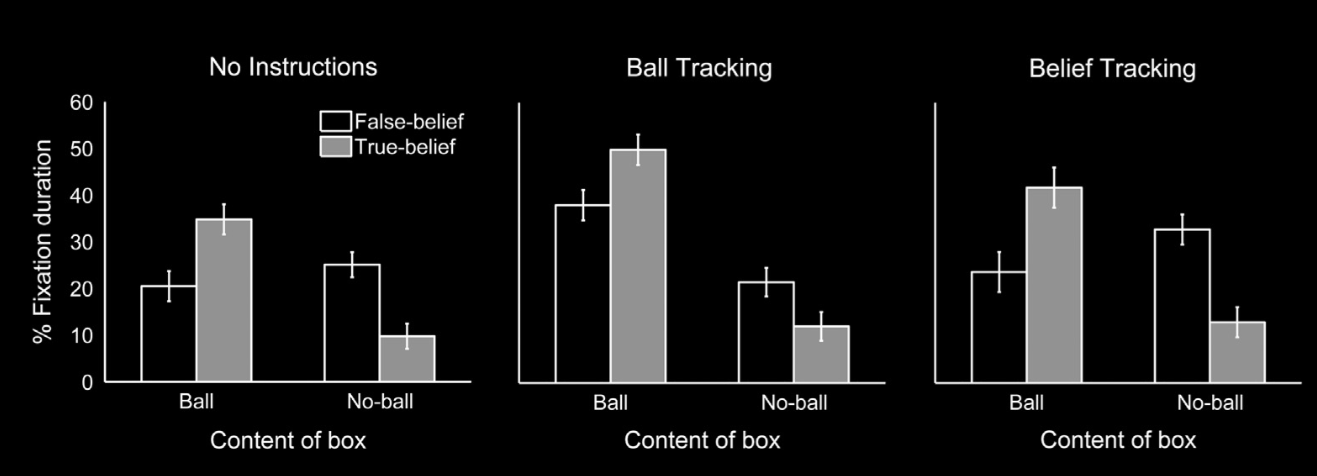

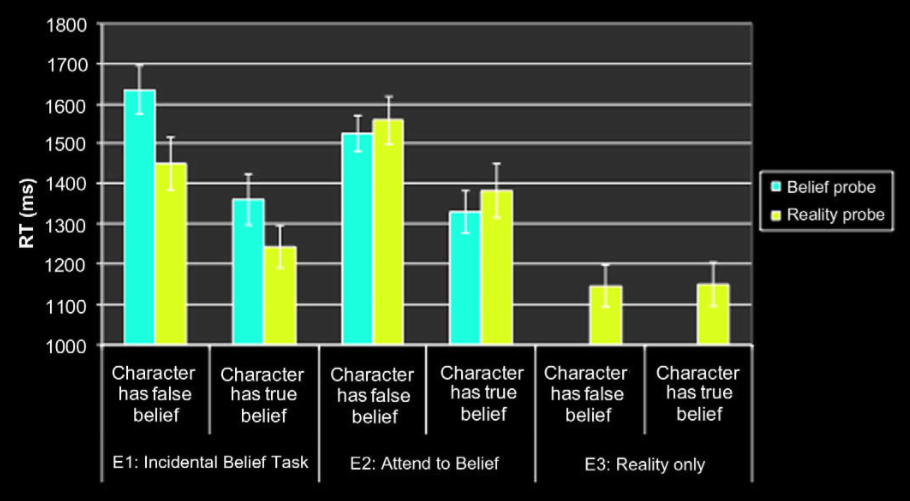

Schneider et al (2014, figure 3)

altercentric interference

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

Kovacs et al, 2010

belief-tracking is sometimes but not always automatic

aside: altercentric interference vs procative gaze

Back & Apperly (2010, fig 1, part)

belief-tracking is sometimes but not always automatic

-- can consume attention and working memory

-- can require inhibition

More evidence for automaticity and non-automaticity.

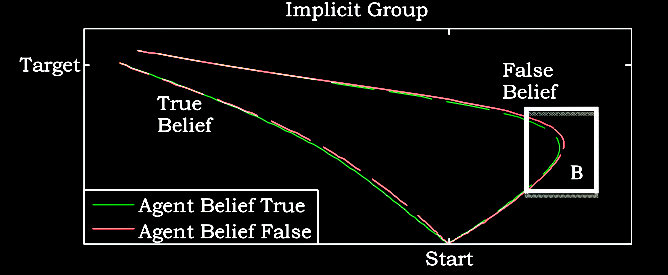

van der Wel et al (2014, figure 1)

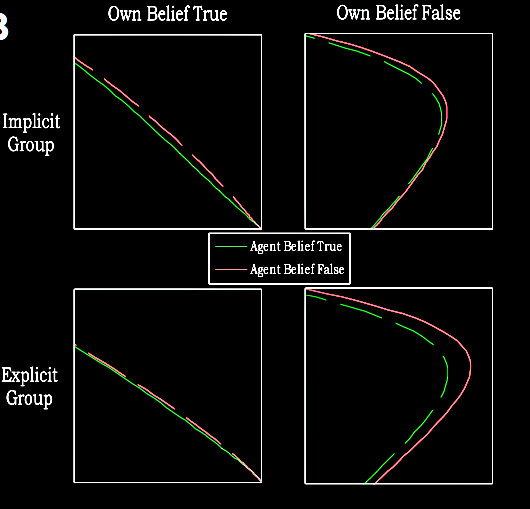

van der Wel et al (2014, figure 2)

van der Wel et al (2014, figure 2)

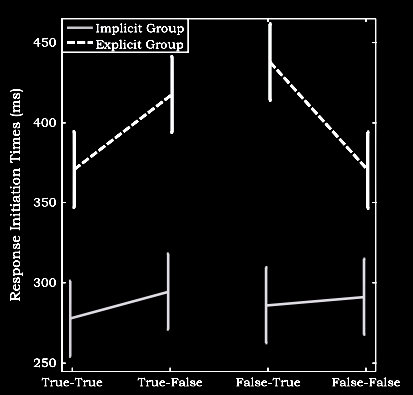

van der Wel et al (2014, figure 3)

‘they slowed down their responses when there was a belief conflict versus when there was not’

Q1

How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing models?

Q2

Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

Q3

Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes but not always automatic? How could belief-tracking be automatic given evidence that it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?