Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

\def \ititle {01: Seeing Red}

\begin{center}

{\Large

\textbf{\ititle}

}

\iemail %

\end{center}

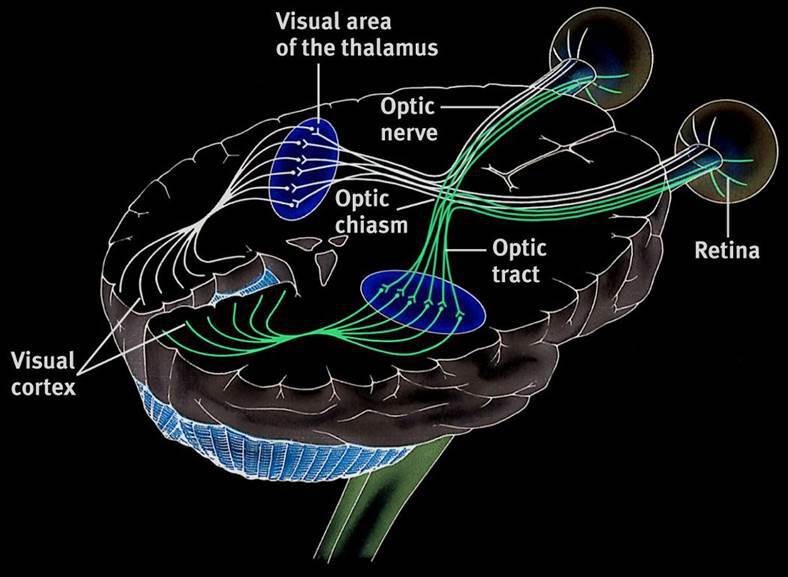

What is the proper domain of a philosopher of mind?

I’m tempted to think that there isn’t one:

almost any philosophical views about minds or actions depend on claims that

are experimentally falsifiable.

People sometimes say claims about phenomenology are immune: they

really can’t be tested. Let’s see ...

This is a module on Puzzling Questions about Minds in Action.

I want to consider a range of cases in which scientific findings

create the sort of puzzles that philosophers seem well-placed

to grapple with.

My plan is to cover a range of topics, as listed on the course outline.

There are several themes that are more or less independent of each other.

I wanted to start with a question about colour experiences because

partly this is a fun introduction.

The other lectures aren’t closely related to this one: I’m guessing that

some people won’t realise the module starts in week 1.

\section{A ‘subject-determining platitude’ about colour}

According to Frank Jackson (1996, pp. 199–200),

it is a ‘subject-determining platitude’

that ‘“red” denotes the property of an object putatively presented in visual experience

when that object looks red’, and likewise for other colour terms.

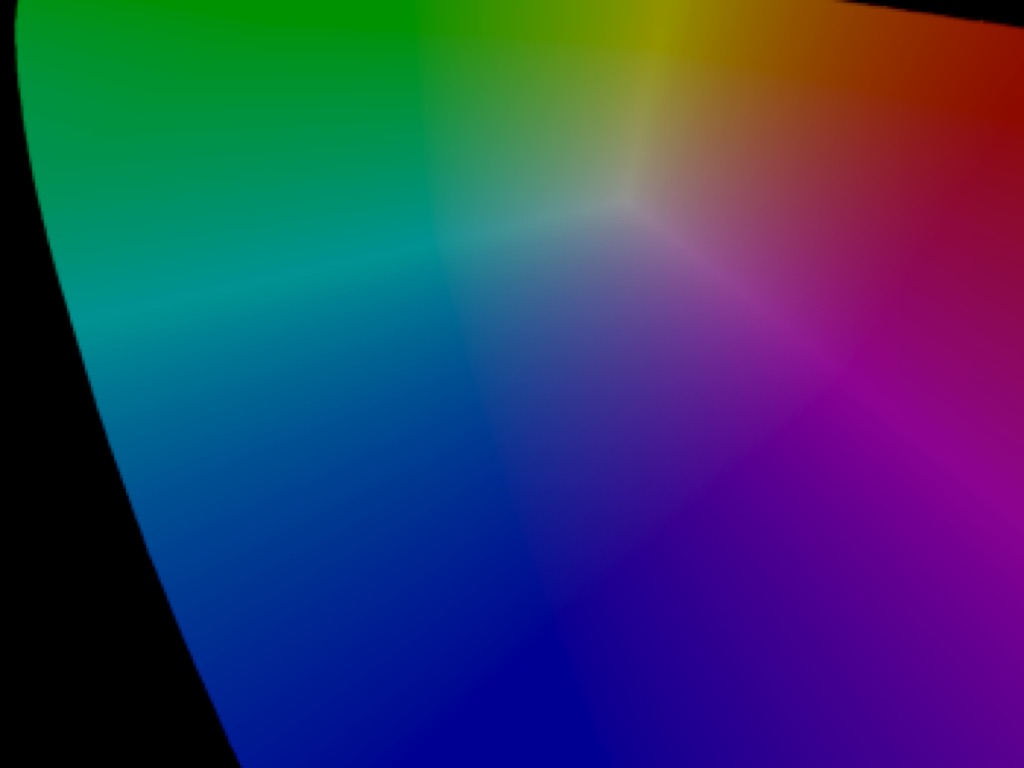

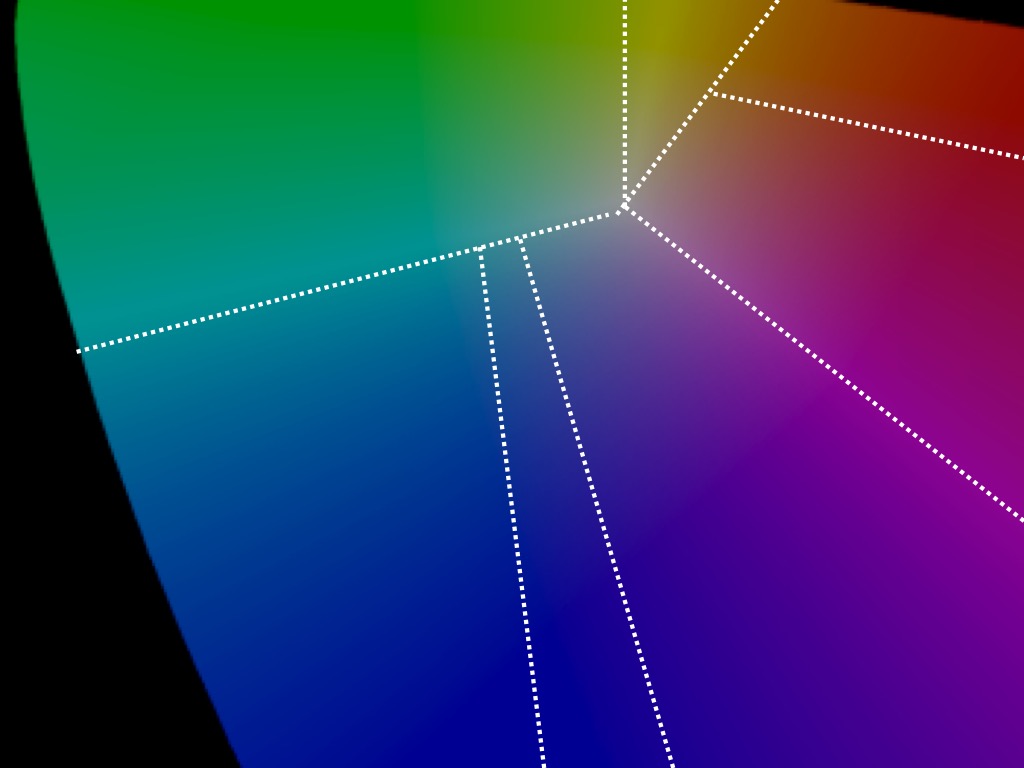

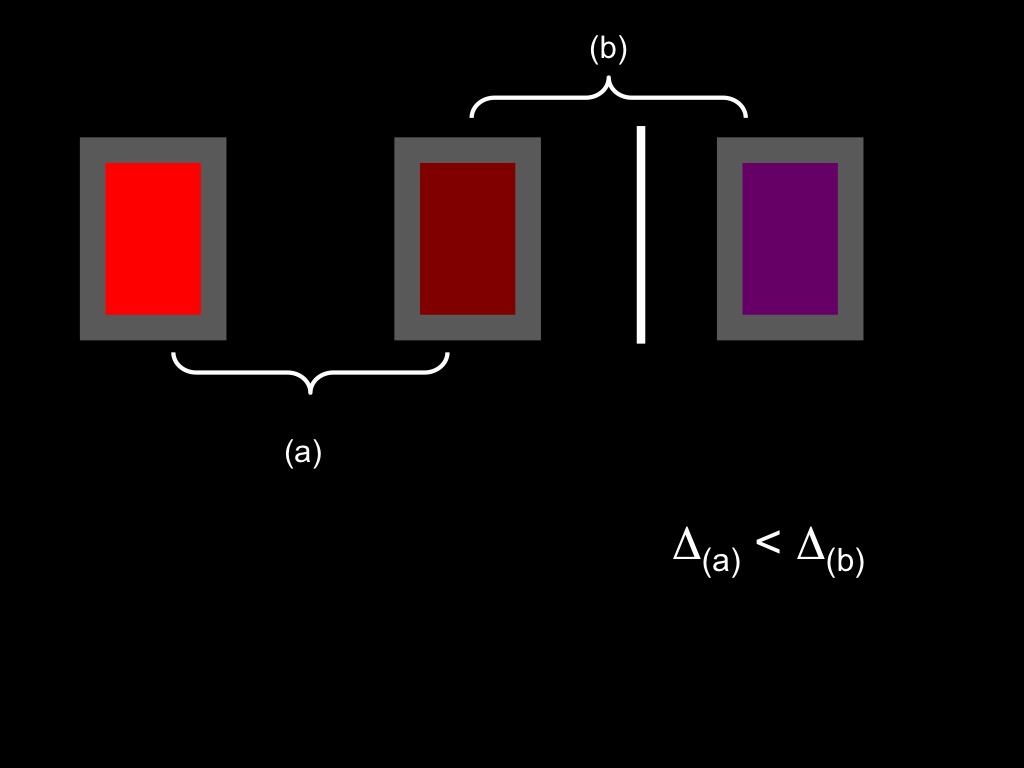

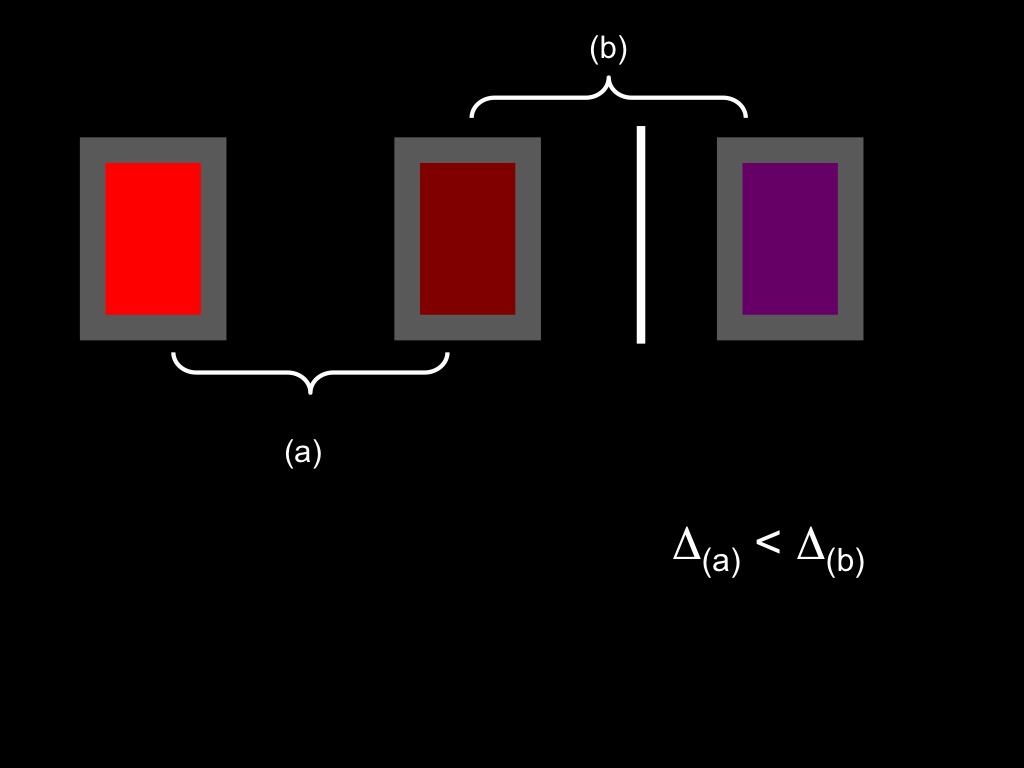

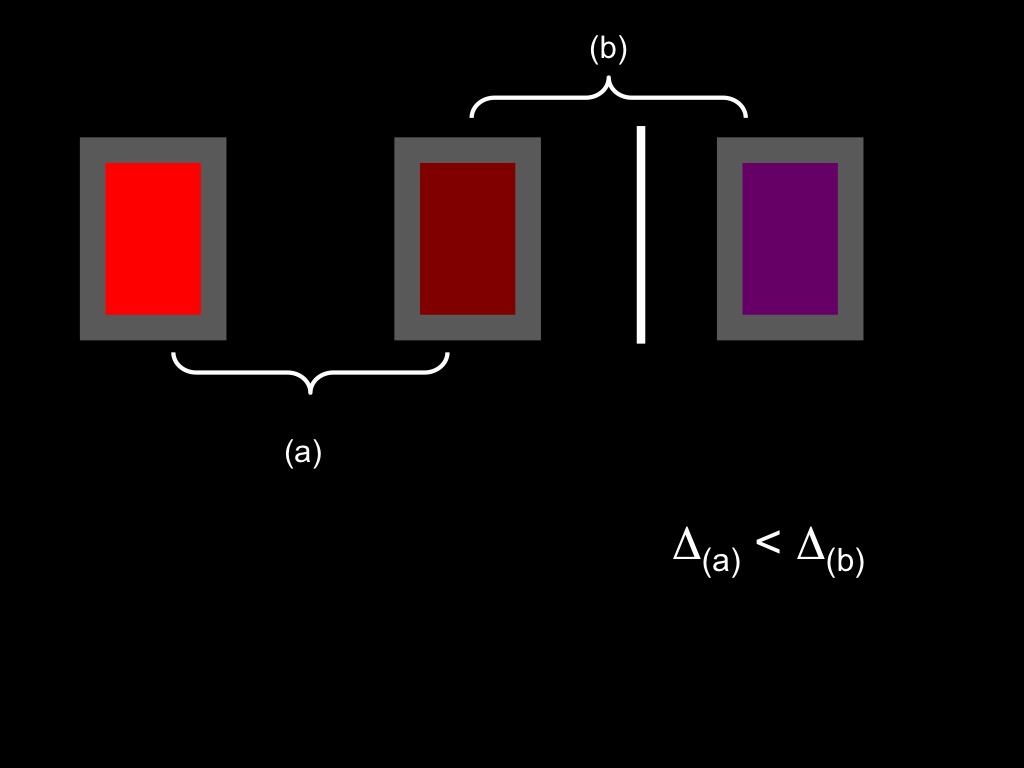

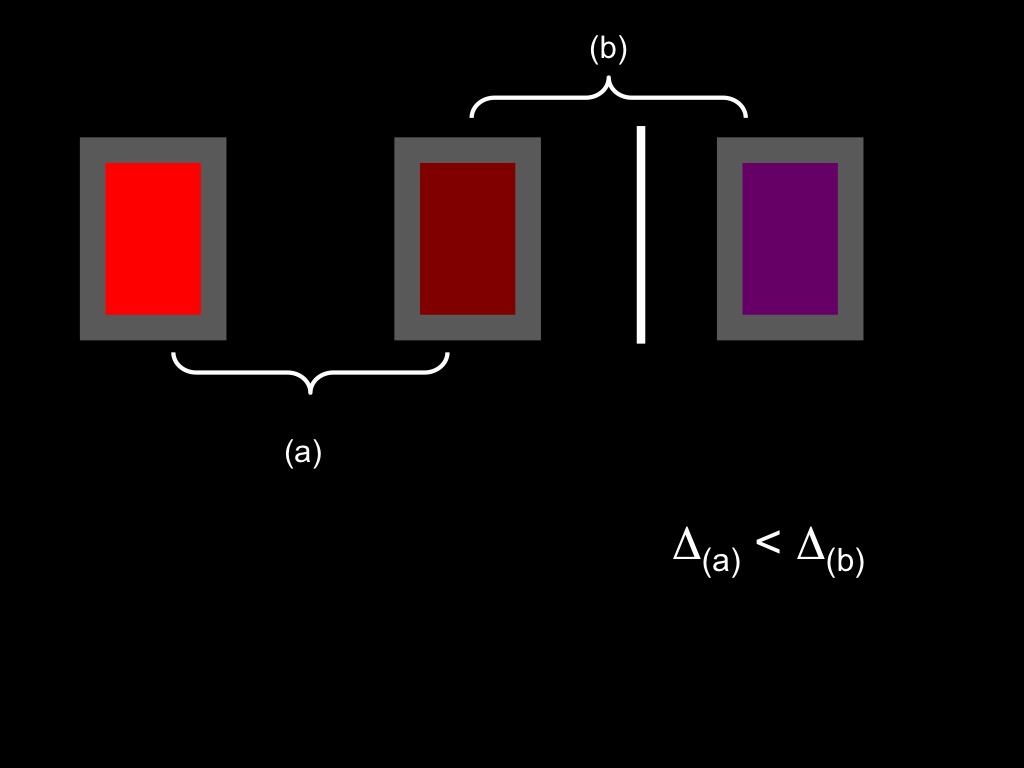

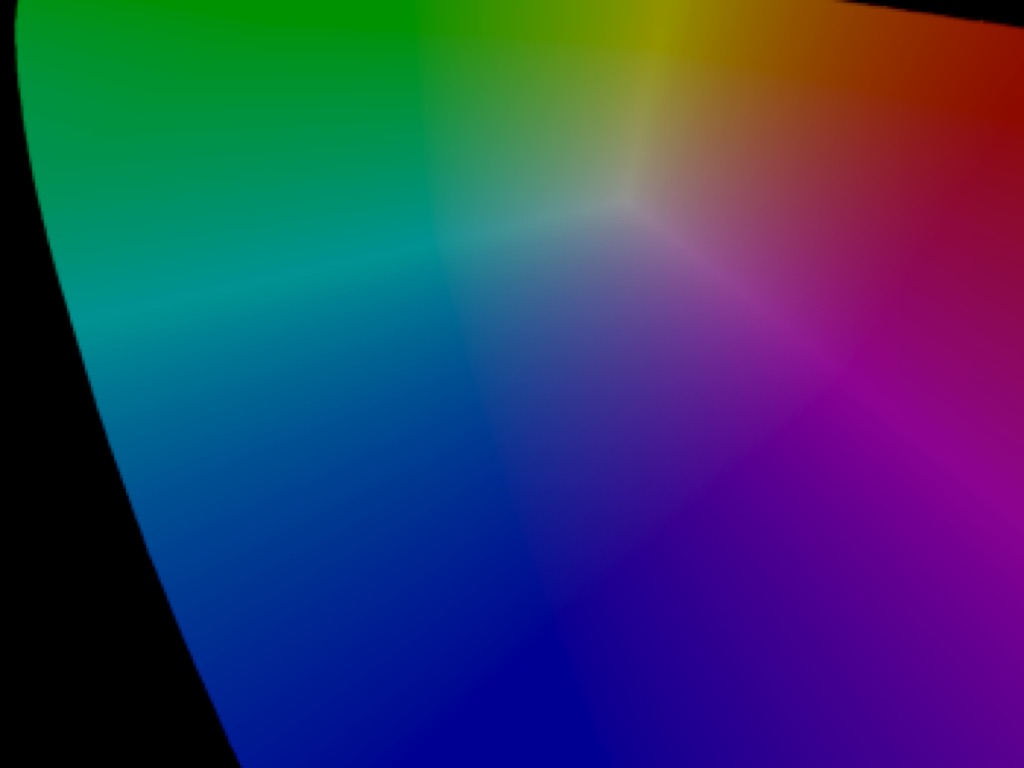

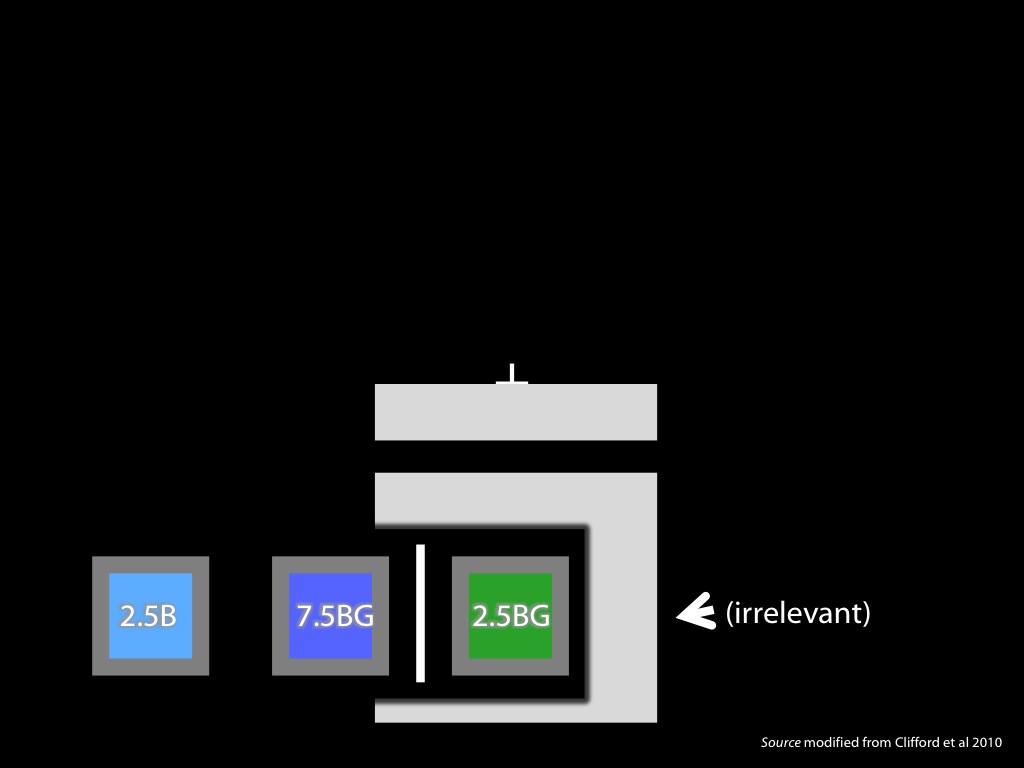

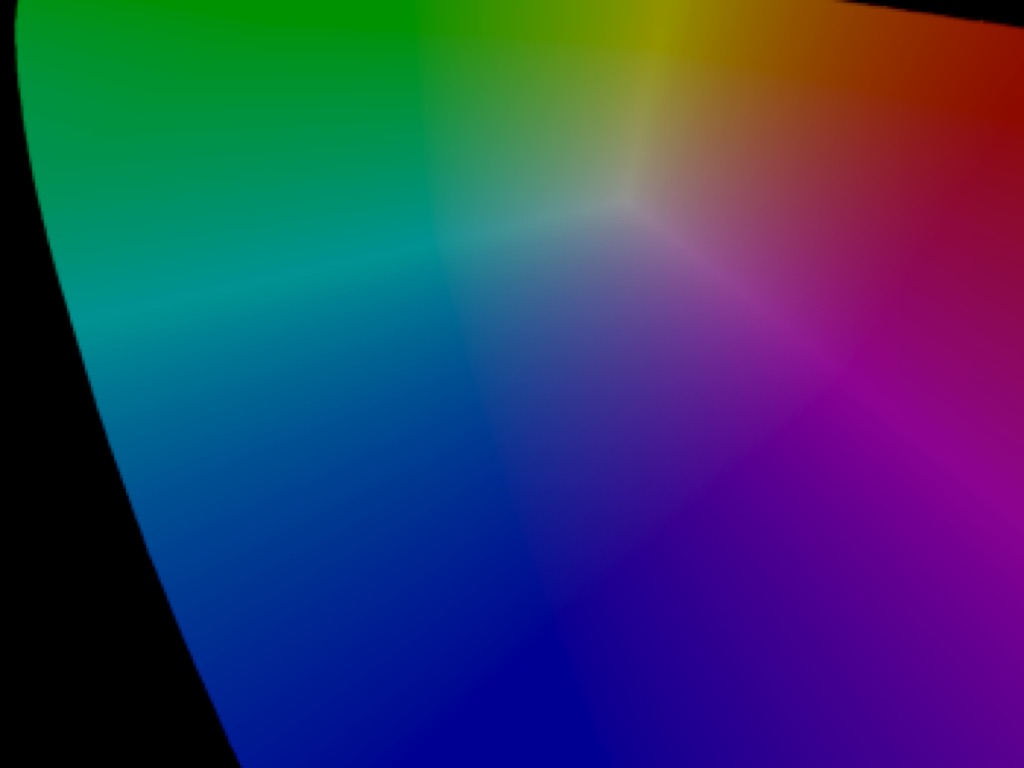

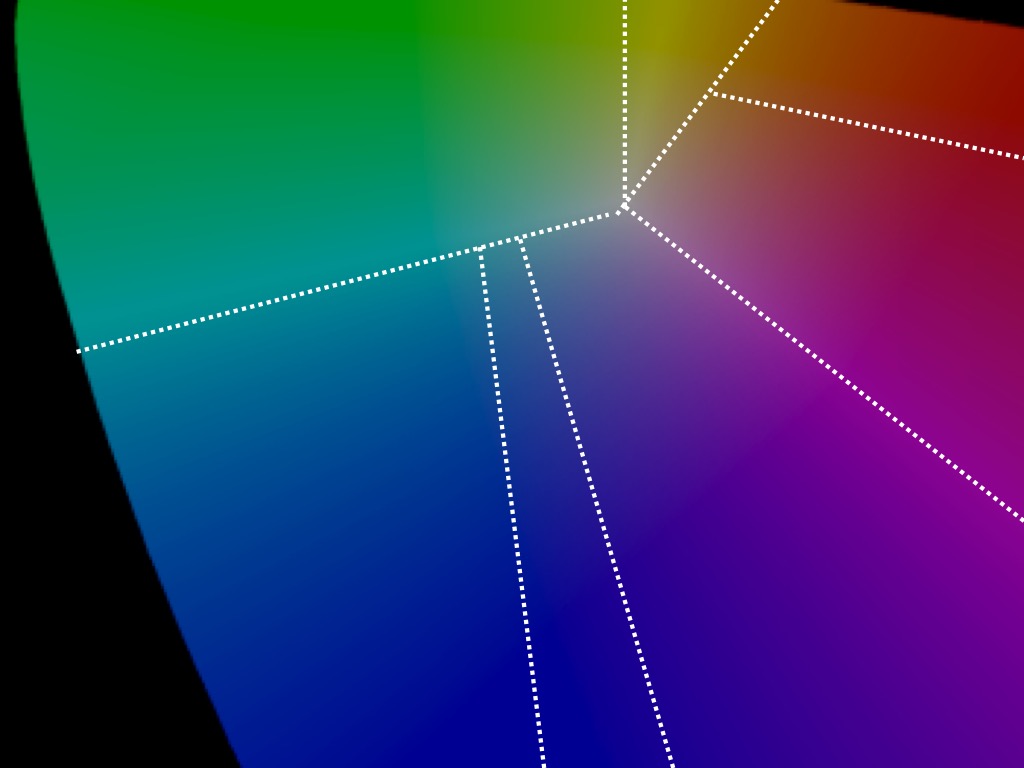

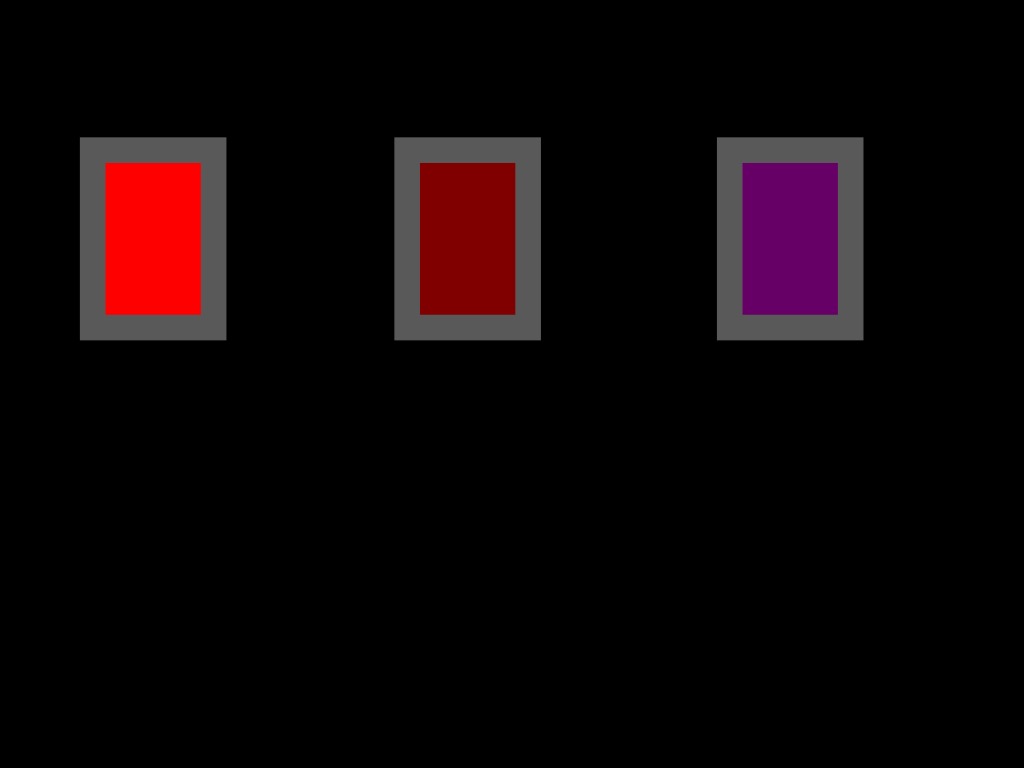

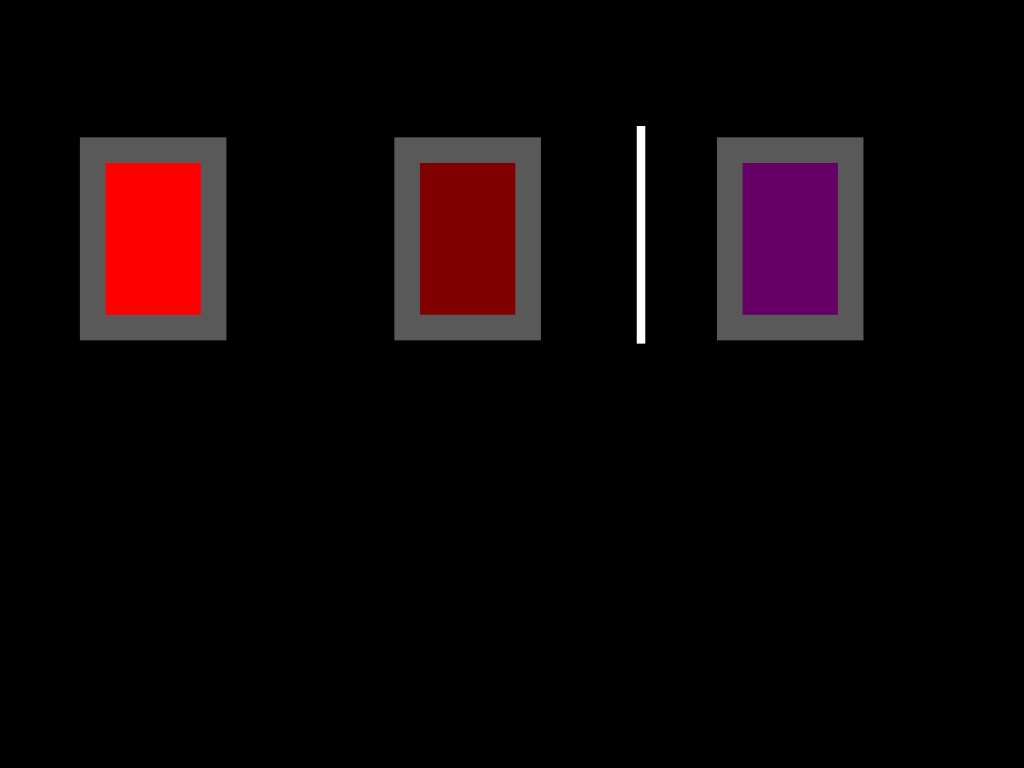

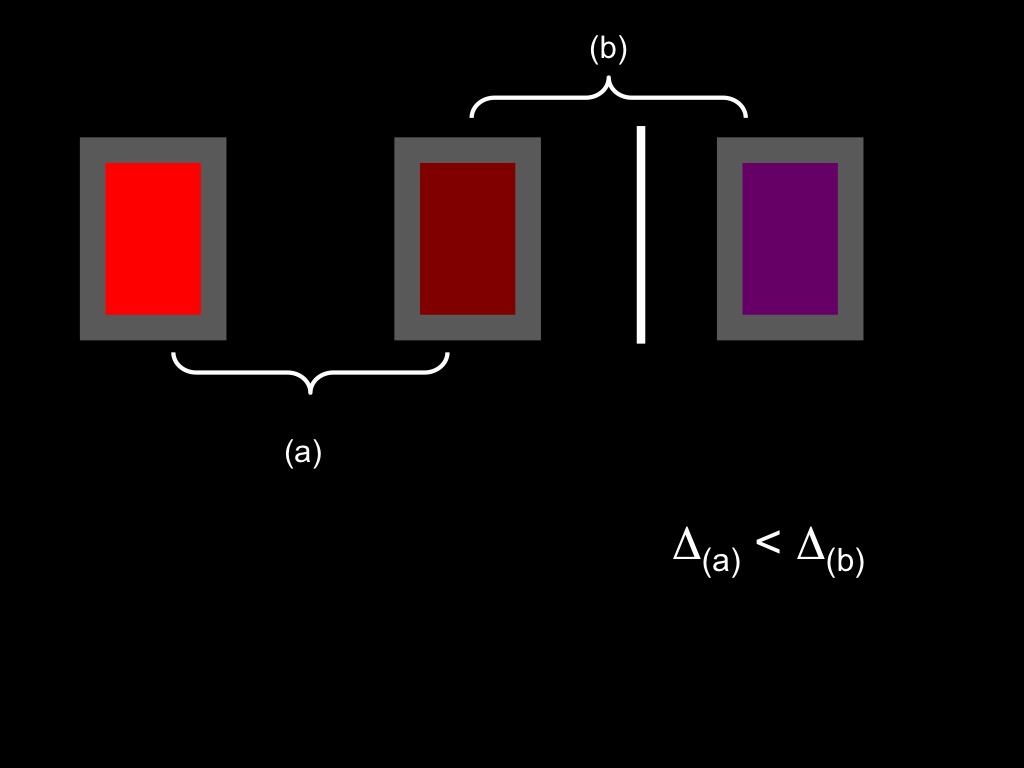

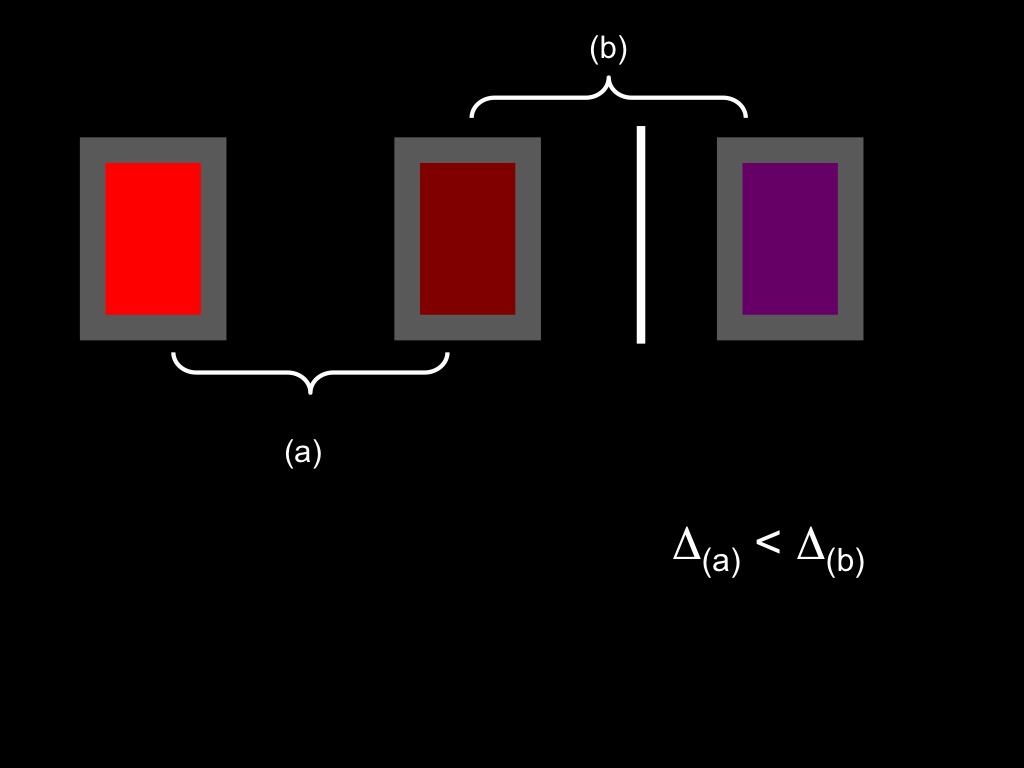

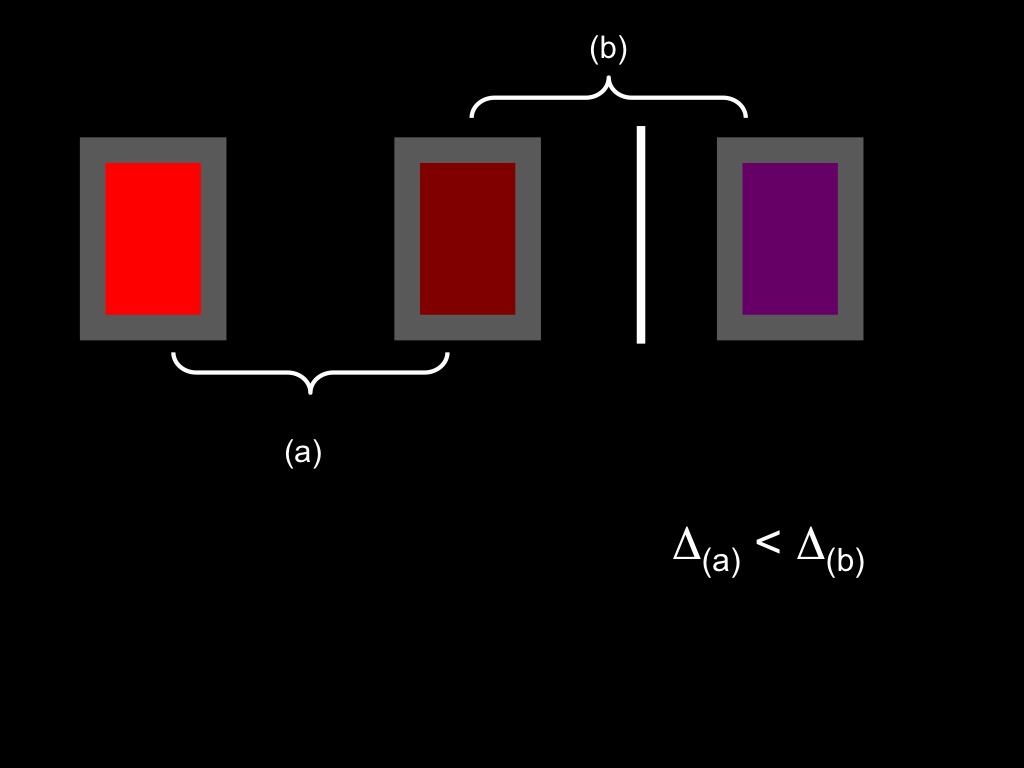

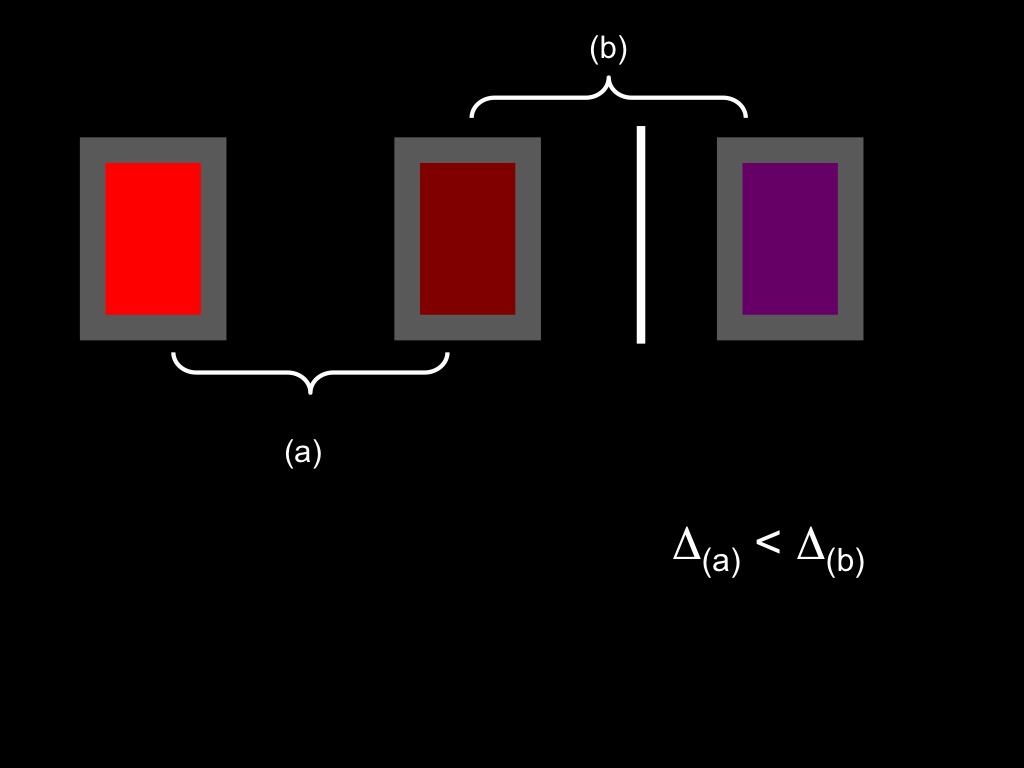

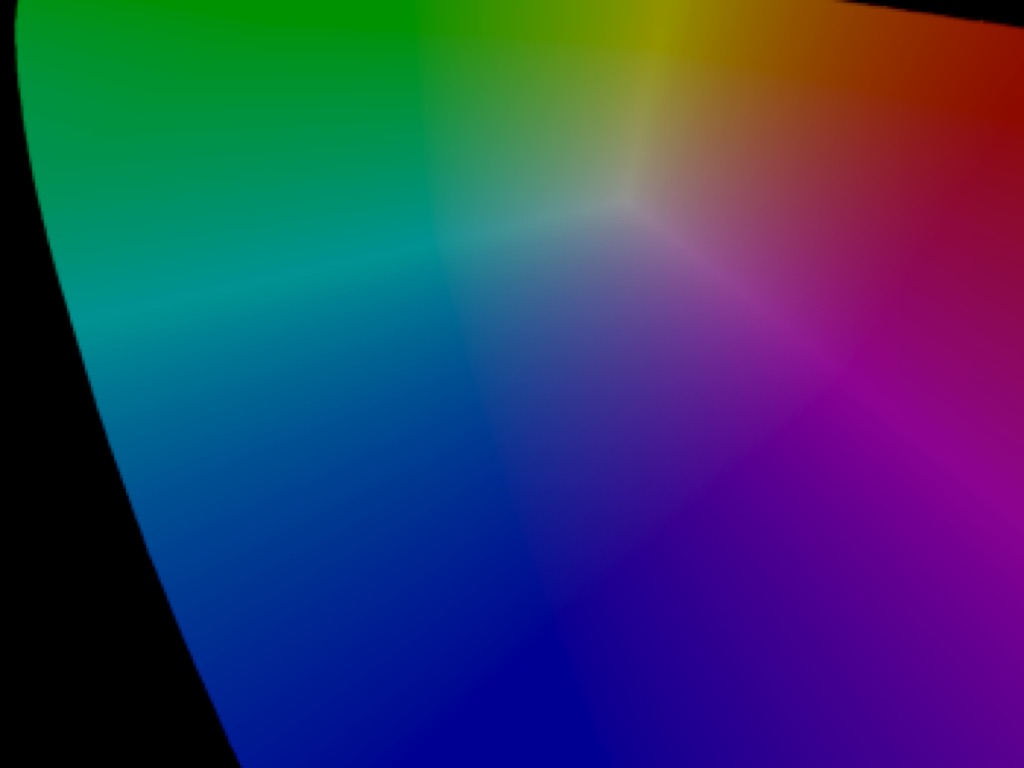

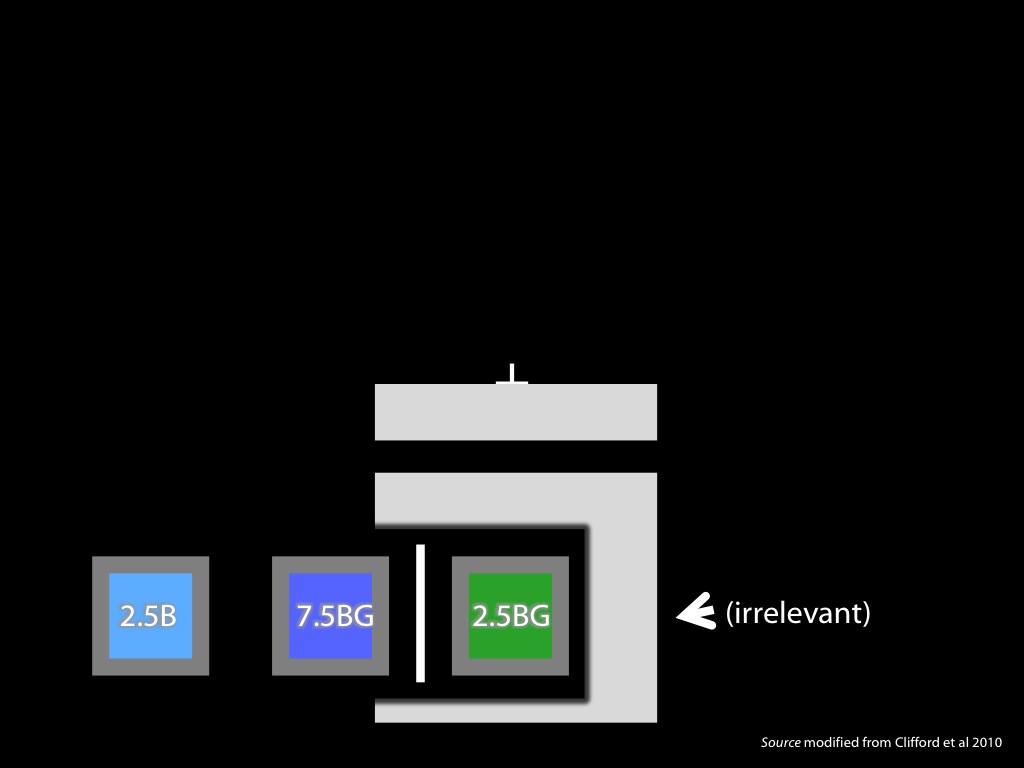

Here are three patches of colour.

The patches are all different colours, but the two leftmost are both the

same colour---they are both blue.

This sounds contradictory but isn't.

In one case we're talking about the particular colours of things,

which I’ll call ‘shades’; in the

other case we're talking about colour category.

Today my focus is not the shades but the categorical colour properties,

properties like red, green and blue.

It has been quite widely accepted (among philosophers, at least) that:

%

\begin{quote}

‘If someone with normal color vision looks at a tomato in good light, the tomato will appear to have a distinctive property—a property that strawberries and cherries also appear to have, and which we call ‘red’ in English’ \citep[p.\ 4]{byrne:2003_color}

\end{quote}

%

Claims such as this are sometimes treated as common ground in controversies about colour.

‘If someone with normal color vision looks at a tomato in good light, the tomato will appear to have a distinctive property—a property that strawberries and cherries also appear to have, and which we call ‘red’ in English’ \citep[p.\ 4]{byrne:2003_color}

‘If someone with normal color vision looks at a tomato in good light,

the tomato will appear to have a distinctive property—a property that

strawberries and cherries also appear to have, and which we call ‘red’ in

English’

(Byrne & Hilbert 2003, p. 4)

It is a ‘subject-determining platitude’ that ‘“red” denotes the property of an object putatively presented in visual experience when that object looks red’, and likewise for other colour terms.

(Jackson 1996, pp. 199–200)

It is a ‘subject-determining platitude’

that ‘“red” denotes the property of an object putatively presented in visual experience

when that object looks red’, and likewise for other colour terms

\citep[pp.\ 199--200]{Jackson:1996zz}.

Is this true?

Does ‘“red” denote the property of an object putatively presented in visual experience

when that object looks red’?

Question:

Does ‘“red” denote the property of an object putatively presented in visual experience when that object looks red’?

Simplifying assumptions:

1. There is a property denoted by ‘red’ which some objects have; call this property red.

2. If the property red (say) is presented in visual experience, then things which have this property thereby differ in visual appearance from things which do not have it.

Question (reformulated):

Do red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things?

\section{How to Measure Phenomenology}

It is perhaps tempting to assume that claims about phenomenology

cannot be tested scientifically.

But this is a mistake. We can use experiments to address the question,

Do things which have the property denoted by ‘red’ thereby appear to be different from things which lack it?

Do red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things?

Recall that our question is,

Do red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things?

How could we tell whether

things which have the property denoted by ‘red’ thereby appear to be different from things which lack it?

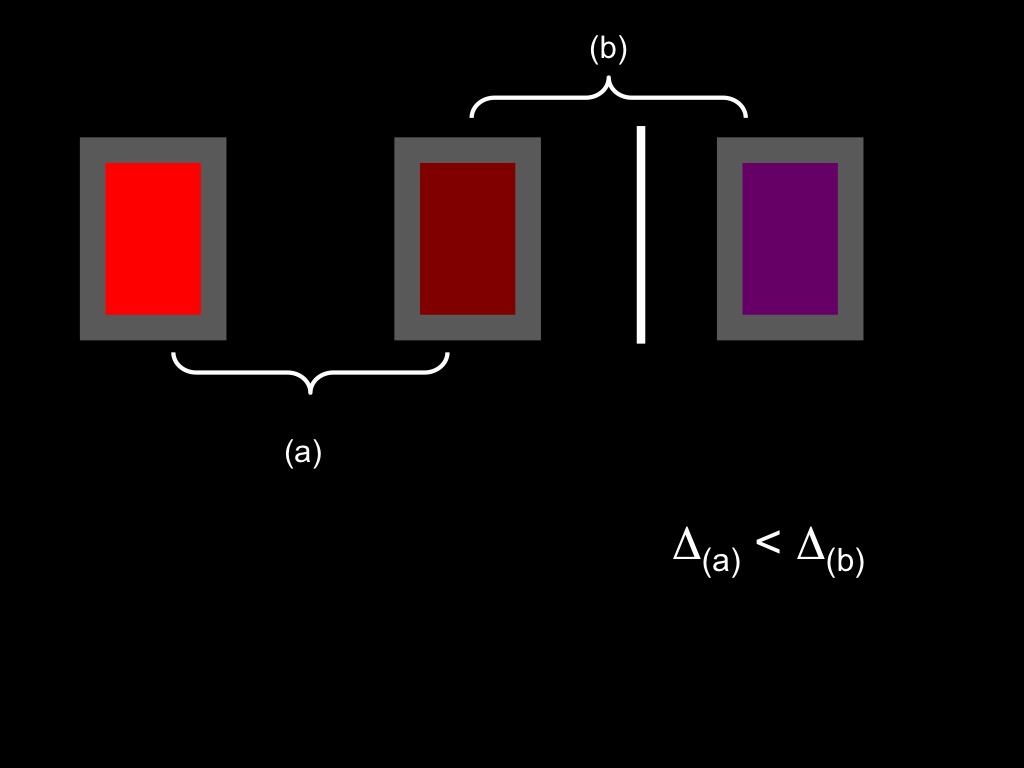

An immediate problem arises from the fact that pairs of things just one of which is \emph{red} (i.e. has the property denoted by ‘red’) differ not only in this way but also in which particular shade of colour they have.

How can we tell whether differences in visual appearance are due in part to differences in being \emph{red} rather than entirely due to differences in shade?

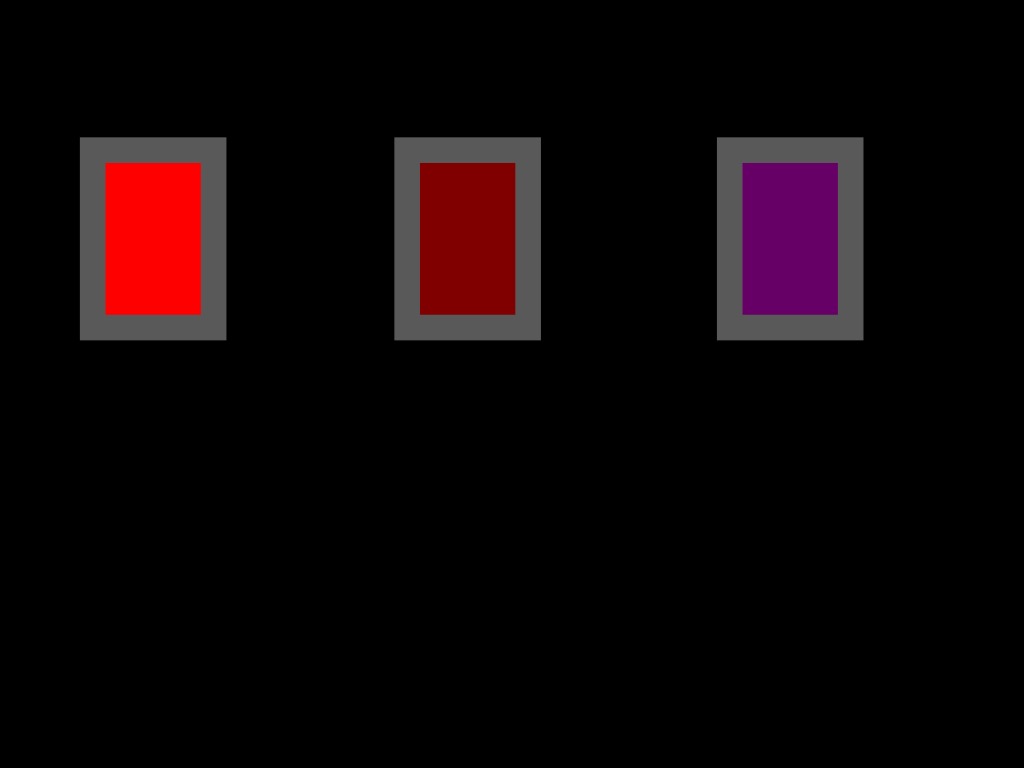

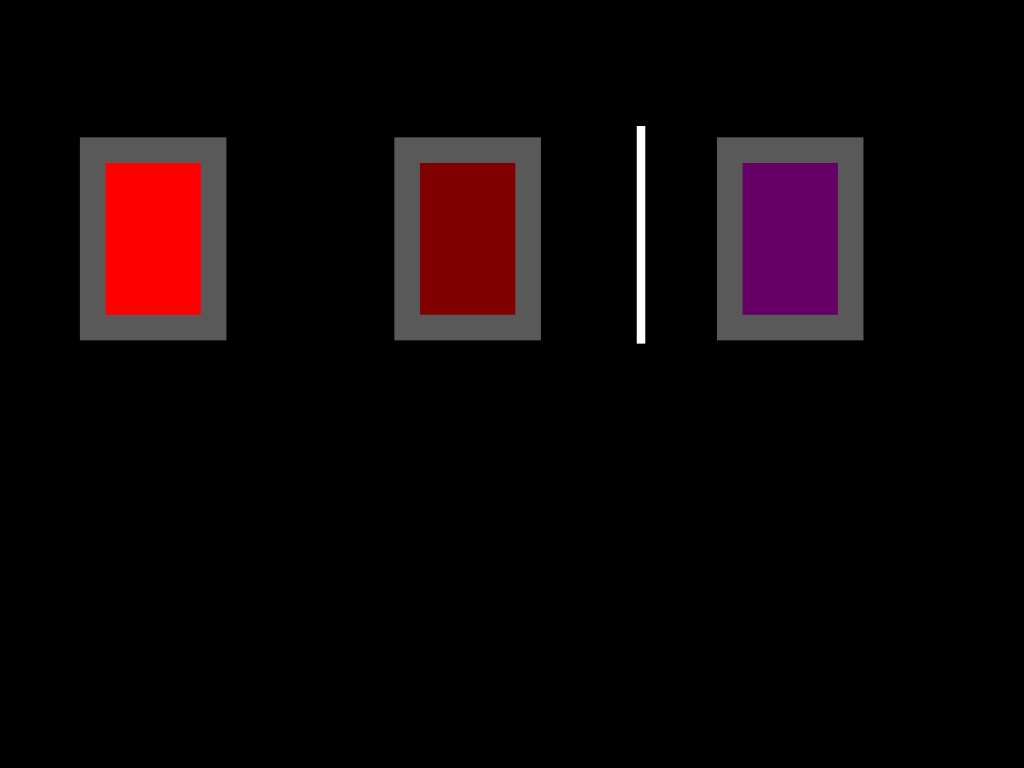

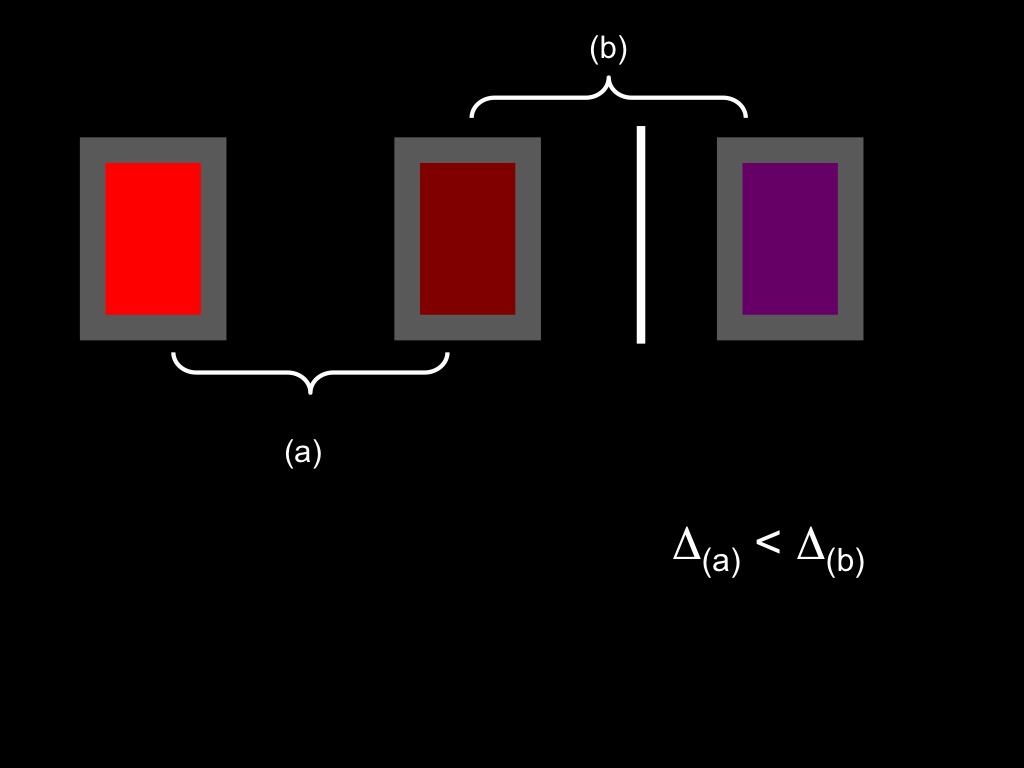

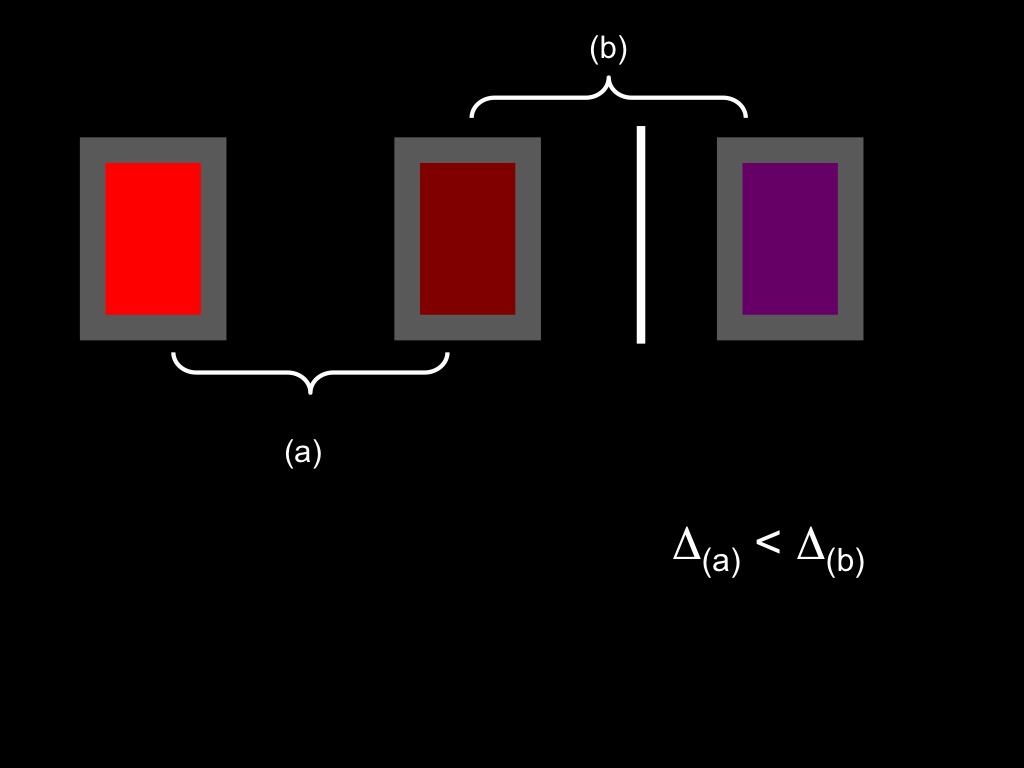

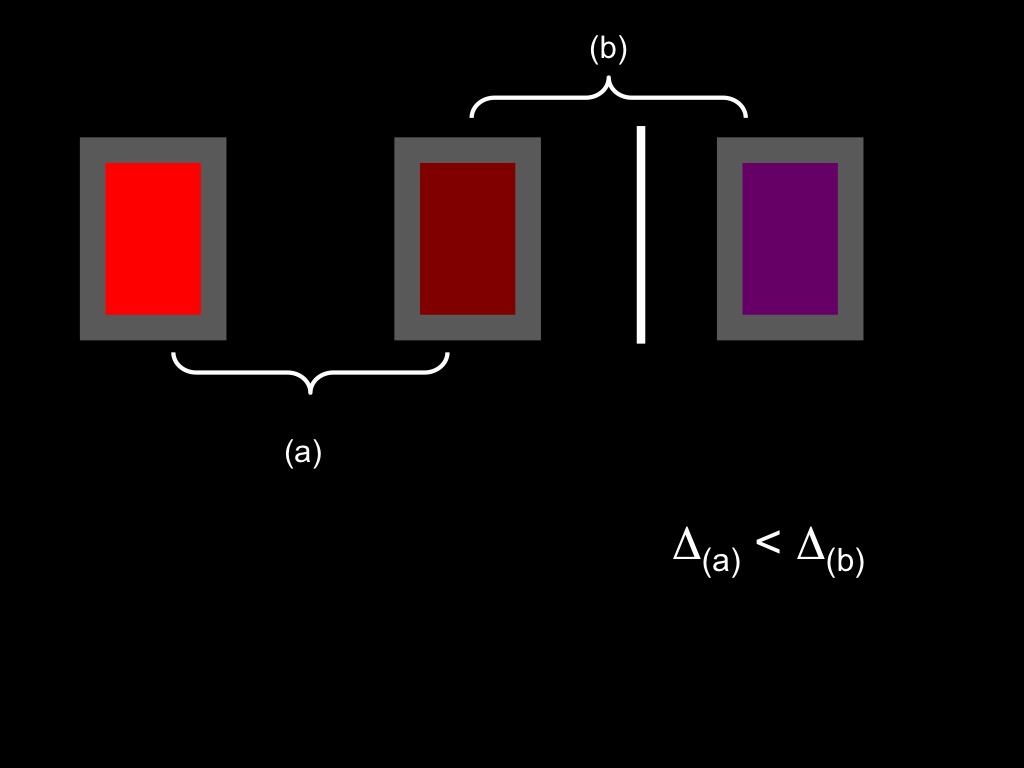

The problem can be overcome by introducing a third thing. Consider constructing a sequence of three things which are indiscriminable except by colour. Let the middle thing be \emph{red}, and let the first thing not be \emph{red}. Now consider the difference between the particular hues of these two things. Ensure the difference is small, but large enough that any two things which differ in hue by this amount are readily discriminable.

Finally, let the third thing be \emph{red}, and let the difference with respect to hue between the third and second thing be the same as the difference between the first and second thing. (Research on colour perception shows that such differences can be equated, and that sequences of this type exist; see

\citealp{kuehni:2001_color} on perceptual uniformity and \citealp{witzel:2013_categorical} on categories.)

Consider the visual appearances of these three things.

The difference in differences ...

Here is the argument. Consider two sequences of sensory encounters: (a) a sequence of sensory

encounters with two phonetic events that do not differ with respect to category (both are

realisations of /d/, say), and (b) a sequence of sensory encounters with two phonetic events that do

so differ (one is a realisation of /d/ the other of /g/, say).11 Let the events encountered in the

first sequence differ from each other acoustically in the same way and by the same amount as the

events encountered in the second sequence differ from each other. (That it is possible to find two

such pairs of events follows from the fact that we enjoy categorical perception of speech.) The two

sequences are depicted in Fig. 3. Now:

1. The second sequence of sensory encounters, (b),

differ from each other more in phenomenal character than the first sequence of sensory encounters,

(a), differ from each other.

2. This difference in differences in phenomenal character is a fact in need of explanation.

3. The difference cannot be fully explained by appeal only to perceptual experiences as of particular shades.

4. The difference can be explained in terms of perceptual experiences as of categorical colour properties.

The fourth step in this argument, (4), needs some filling in. How would the thesis that categorical

perception of speech is a form of perceptual experience explain the difference in differences in

phenomenal character? If the thesis is true, the first sequence of sensory encounters, (a), involves

two perceptual experiences as of a single phoneme whereas the second sequence of encounters, (b),

involves perceptual experiences as of different phonemes.12 Let us assume (not very controversially)

that perceptual experiences have phenomenal characters and that which phenomenal character a

perceptual experience has depends in part on what it is as of.13 It follows that differences in what

perceptual experiences are as of can explain differences in the phenomenal characters of those

perceptual experiences. In particular, if it is a fact that (b) involves perceptual experiences as

of different things whereas (a) does not, this could explain why the sensory encounters in (b)

differ in phenomenal character in a way that the sensory encounters in (a) do not.

5. There is no better explanation of the difference.

\begin{center}

\includegraphics[scale=0.25]{img/categorical_colour_difference3.jpg}

\end{center}

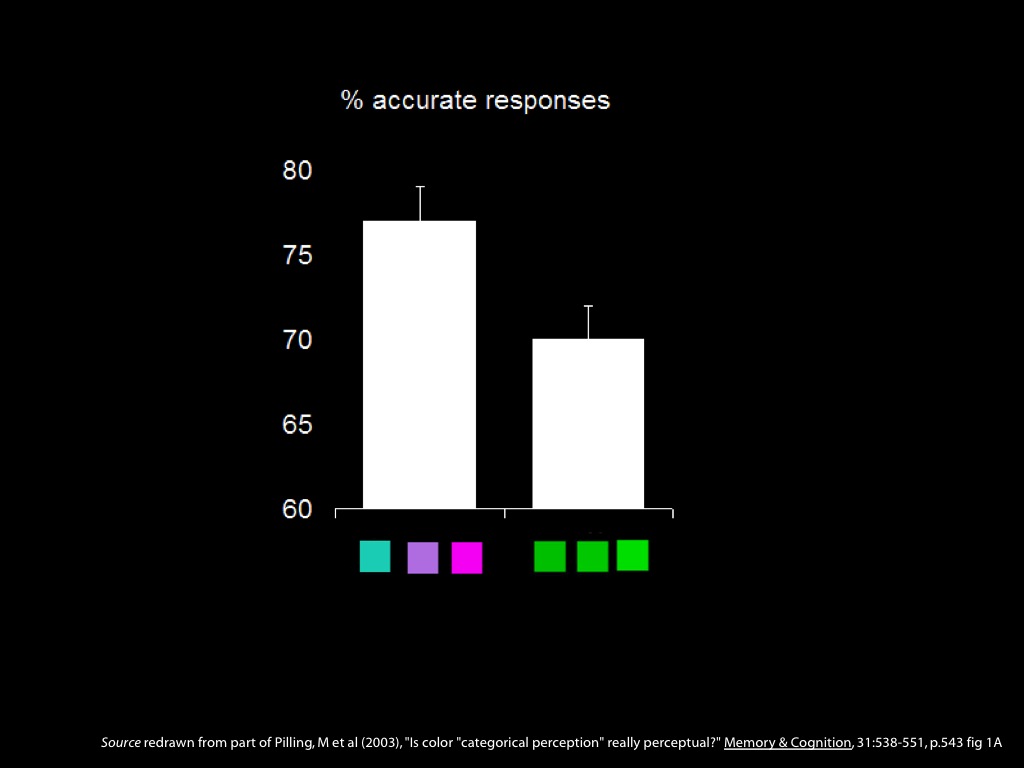

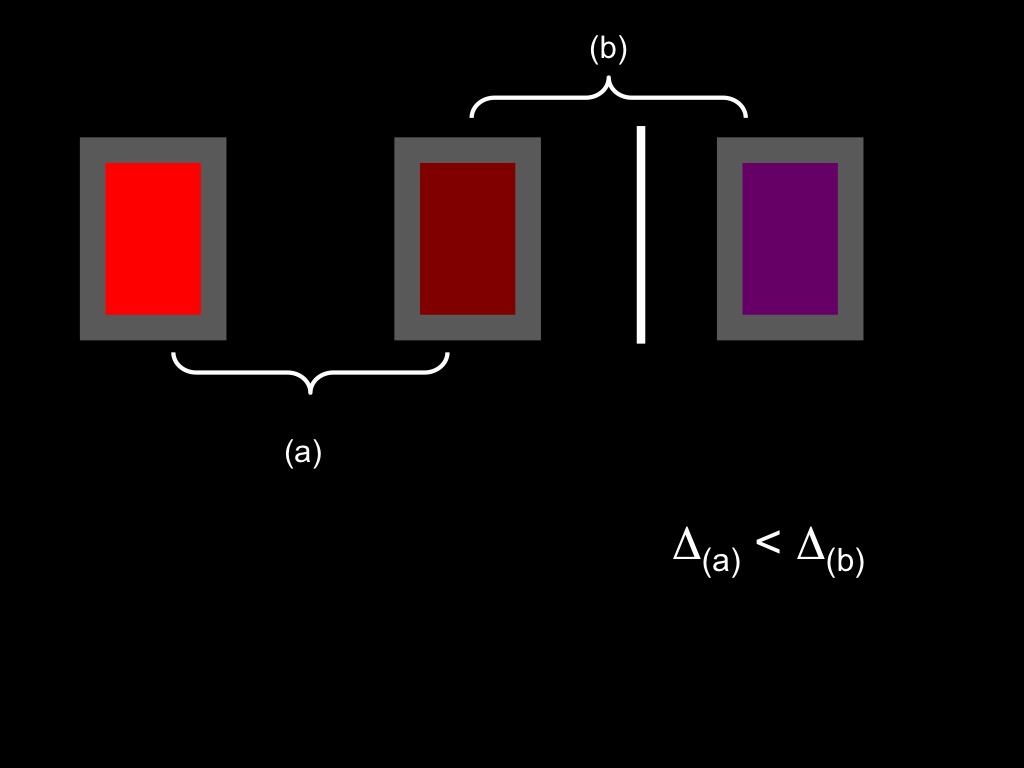

Hypothesis: Red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things.

1. Redness will influence discrimination.

2. Redness will influence similarity judgements.

3. Redness will influence pop-out effects.

4. Redness will influence perceptual grouping.

Let me show you how speed an accuracy of discimination are usually measured.

This is a 2-alternative forced-choice task (2AFC).

Witzel & Gegenfurtner 2018, figure 5

\begin{center}

\includegraphics[scale=0.25]{img/categorical_colour_difference3.jpg}

\end{center}

Hypothesis: Red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things.

1. Redness will influence discrimination.

2. Redness will influence similarity judgements.

3. Redness will influence pop-out effects.

4. Redness will influence perceptual grouping.

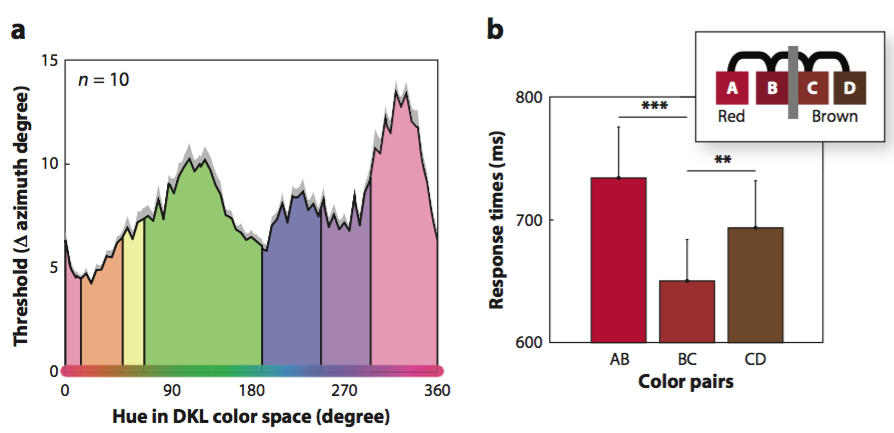

‘Category effects on color perception. (a) Categorical sensitivity. The diagram shows how the sensitivity to color differences changes across hue. The x-axis corresponds to hue in DKL color space, and the y-axis to discrimination thresholds. Adapted from Witzel & Gegenfurtner (2013). Note that the green-blue boundary is unlike the others in that it coincides with a local minimum of discrimination thresholds. (b) Categorical facilitation. The bars along the x-axis of the main graphic correspond to color pairs that are composed of the colors illustrated by the inset. The y-axis of the main graphic represents response times in speeded discrimination. Note that discriminating the color pair BC, in which B and C belong to different categories (i.e., red and brown), is fastest even though the distances between colors control for sensitivity to color differences. Adapted from Witzel & Gegenfurtner (2016). Abbreviation: DKL, Derrington-Krausfopf- Lennie. ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.’

Difference between the two kinds of discrimination effect will be important for us later ...

Could you object that the difference in appearance between red and non-red things

is already built into the metric used for the colour space? In that case you would not

expect additional effects of categorical colour property on appearance. These effects would be

already taken into account in the measurements of similarity.

To answer this objection we need to note that there are multiple ways of

measuring perceptual similarity.

In this case, the researchers used JNDs.

They have previously shown that category boundaries (as specified by an individual

subject’s colour words) do not affect JNDs. That is, JNDs are not generally smaller at the

category boundaries \citep{witzel:2013_categorical}.

But when you take pairs of colours that are, say, 3 JNDs apart, then whether or not

the pair straddles a category boundary will affect speed and accuracy of discimination

\citep{witzel:2014_categorical}.

So we can be confident that using JNDs to measure perceptual similarity does not

take into account differences in the ways categorical colour propreties appear.

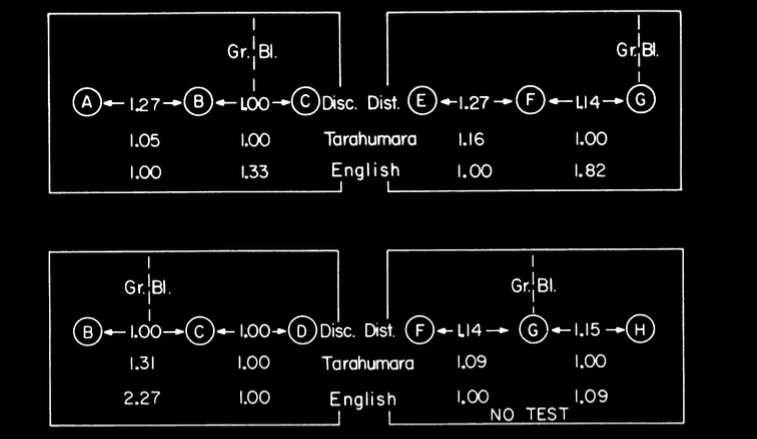

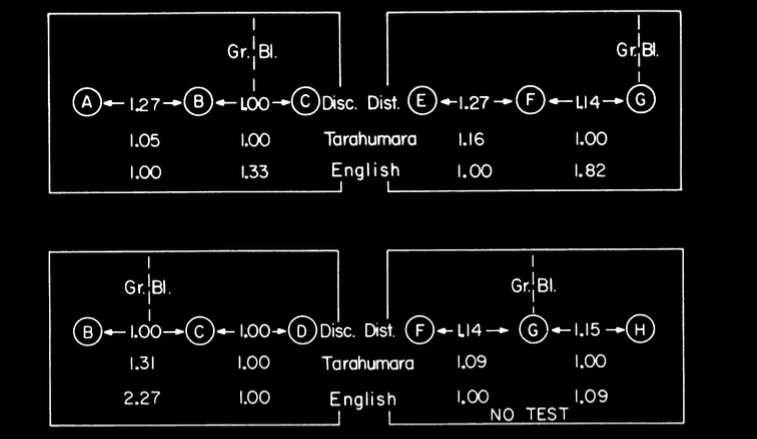

Kay & Kempton 1984, figure 3

In brief: Kay and Kempton contrasted the responses of native English

speakers (who have words for green and blue) with native Tarahumara (a Uto-Aztecan language of

northern Mexico) speakers, whose basic colour words mark no such distinction.

Here you see a triad of colours, A, B and C.

Kay and Kempton first measured ‘discrimination distance’.

That is, how far apart are each of these in terms of JNDs?

As it turns out, JNDs are not affected by which categorical colour properties you can name

\citep{witzel:2013_categorical}.

So we would expect discrimination distance to be approximately the same for all

participants. (Some studies do measure discrimination distance for

each subject individually and find indiviudal differences; e.g. \citep{witzel:2014_categorical}).

In this case, you can see that A is further from B in JNDs than B is from C.

‘discrimination distance’:

‘The scale of psychological distance between colors we take as the "real" scale

for present purposes is called discrimination distance. The unit of this

scale is the just noticeable difference (jnd), that is, the smallest physical

difference in wavelength that can be detected by the human eye.’

\citep[p.~68]{kay_what_1984}

Next Kay and Kempton measured how visually similar their subjects judged these

samples to be.

To do this, they showed them different triads of colours and asked them,

Which is the most different from the other two?

For each pair they then computed the proportion of times that pair was split.

(As they write: ‘The psychological distance between A and B relative to other

stimulus pairs in the set is given by the proportion of times A and B are split

by the subject's selection of one of them as the most different item in the

triad.’ p. 70.)

This is what you see from the Tarahumara speakers and the English speakers

under the circles.

Looking at the numbers, you can see that

the English speakers tended to split B and C more often than A and B,

whereas the Tarahumara speakers did the opposite.

And note that the B-C pair crosses the blue-green boundary.

What does this mean?

‘The presence of the blue-green lexical category boundary appears to cause

speakers of English to exaggerate the subjective distances of colors close to

this boundary. Tarahumara, which does not lexicalize the blue-green contrast,

does not show this distorting effect.’

\citep[p.~77]{kay_what_1984}:

‘the English speaker judges chip B to be more similar to A than to C because

the blue-green boundary passes between B and C, even though B is perceptually

closer to C than to A.’

This is exactly the sort of evidence that should persuade us

that red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things.

Here’s another comparison.

In this case, the discrimination distance (in JNDs) was the same between

the three colour samples.

Both groups thought that B and C are most different, and these cross

the blue-green boundary. But this effect was stronger in the English speakers.

There were some other comparisons that I won’t talk about.

Overall, this is evidence for the conclusion that

red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things.

Is the effect due to

visual appearances

or merely to

the ‘Name Strategy’?

The ‘name strategy’: ‘We propose that faced with this situation the

English-speaking subject reasons

unconsciously as follows: “It's hard to decide here which one looks the most

different. Are there any other kinds of clues I might use? Aha! A and B are

both CALLED green while C is CALLED blue. That solves my problem; I'll pick C

as most different.” ... this cognitive strategy ... we will call the

“name strategy”’ \citep[p.~72]{kay_what_1984}.

‘According to the name strategy hypothesis, the speaker who is

confronted with a difficult task of classificatory judgment may use the lexical

classification of the judged objects as if it were correlated with the required

dimension of judgment even when it is not, so long as the structure of the task

does not block this possibility’ (p. 75).

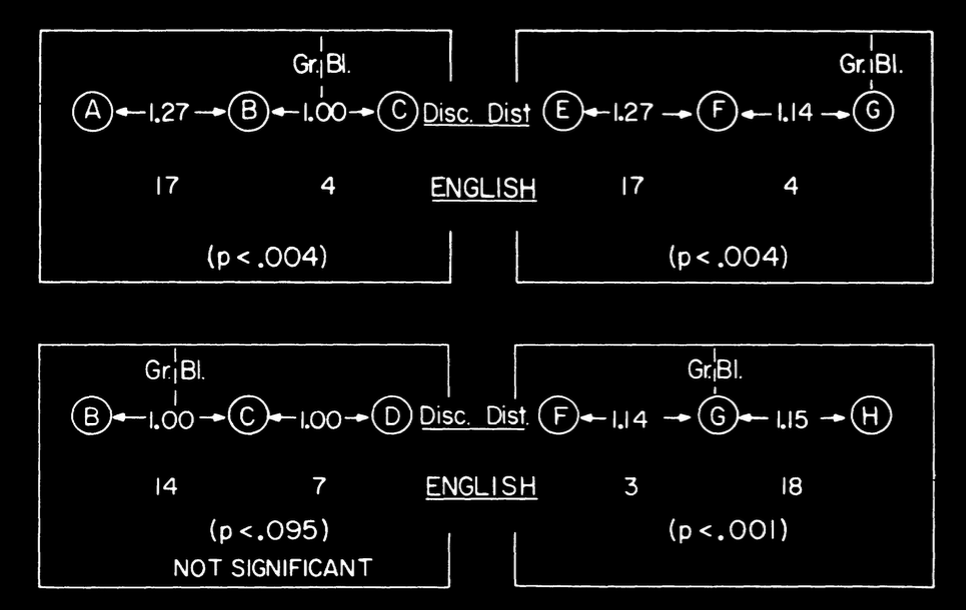

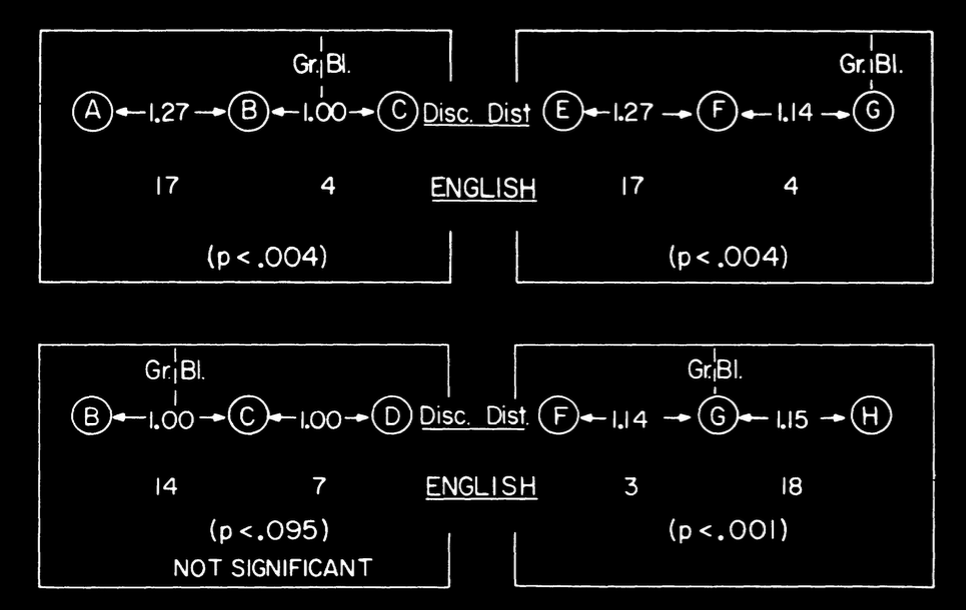

Kay & Kempton (1984, Experiment 2)

They consider a modification to block

use of the naming strategy.

This involves showing subjects only two of the three

stimuli at any one time (Experiment 2).

(‘The three chips were arranged in a

container with a sliding top that permitted the subject to see alternately

either of two pairs of the three chips, but never all three at once. For

example, in triad (A, B, C) the pairs alternately made visible were (A, B) and

(B, C).’) When they do this, categorical colour properties have no effects on

perceptual judgements of similarlity. ‘Subjective similarity judgments follow

discrimination distance and reflect no influence from lexical category

boundaries’ (p. 73).

Kay & Kempton 1984, figure 4

Here are the results from experiment 2.

In this case, there are only English speaking subjects.

And the numbers for the subjects are

‘simply the number out of 21 subjects who chose the indicated pairwise subjective distance as larger.’

The results now are quite different.

Top left: subjects appear to go with discriminability (JND distance)

rather than colour category.

Bottom left: when discriminability (JND distance) is equated,

subjects show no significant effect of colour category (although there is a trend).

‘Subjective similarity judgments follow

discrimination distance and reflect no influence from lexical category

boundaries.’ \citep[p.~73]{kay_what_1984}

conclusion: red things do not differ in visual appearance from non-red things

Conclusion: the name strategy explains the effects of Experiment 1.

Red things do not differ in visual appearance from non-red things

objection:

‘I’d like you to tell me which is bigger: the difference in greeness between the two chips on the left or the difference in blueness between the two chips on the right.’

They changed the instructions between Experiment 1 and Experiment 2.

This change invites the objection that the instruction

encouraged

subjects to attend to hue and ignore other features of the colour.

So the results are inconclusive.

Why spend so long on flawed research from which we can’t draw a conclusion

either way? To illustrate that the issue is quite complex,

and that you have to read papers carefully!

(You aren’t supposed to discuss minutae of papers in your essays;

you’re not an expert on stats or methods. But if you cite a paper

in support of a claim, you’d better be as sure as you can that the

paper really does support that claim.)

Witzel & Gegenfurtner (2014)

++ discrimination and category boundary measurements for individual subjects

++ more categories tested (‘Rosa’, ‘Braun’, ‘Orange’, ‘Gelb’, ‘Gruen’, ‘Blau’, and ‘Lila’)

According to more recent research discussed in \citep{witzel2014category}

(a published report is not yet available), in fact they do not. That is,

whether things are \emph{red} appears to make no difference to judgements

of similarity (\citealp{witzel2014category}; actually these researchers did

not test ‘red’, but they did test the German terms ‘Rosa’, ‘Braun’,

‘Orange’, ‘Gelb’, ‘Gruen’, ‘Blau’, and ‘Lila’.) This indicates that things

which are \emph{red} do not thereby differ in visual appearance from things

that are not \emph{red}.

++ prototype effects found, but ‘there were literally no effects at boundaries’ (p.c.).

From correspondence: ‘that experiment was originally reported in the same

paper as the "Categorical facilitation" one, but it was too long. Up to now

it is only in my thesis and there is the abstract, which I paste you below.

Note, however, that we found slight traces of perceptual magnet effects

around prototypes when reanalysing the data later on, which is reflected in

the book chapter, but not the older abstract. The found effects are quite

systematic (happening at almost all prototypes), but also extremely weak,

and there were literally no effects at boundaries.’

How can we defend the view that red things differ in visual appearance from

non-red things? Maybe there are differences in visual appearance that we

are not aware of? Maybe the judgements of similarlity are not sensitive

enough? (But note that \citet{witzel2014category} did find evidence for the

effect of prototypes on judgements of similarity, so the method seems good:

to test this, the three colour samples were arranged so that the prototype

was positioned between a middle and an outer sample. ‘Colours close to the

prototypes were judged to be more similar than they actually were in terms

of pure discrimination’.)

\begin{center}

\includegraphics[scale=0.25]{img/categorical_colour_difference3.jpg}

\end{center}

Hypothesis: Red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things.

1. Redness will influence discrimination.

2. Redness will influence similarity judgements.

3. Redness will influence pop-out effects.

4. Redness will influence perceptual grouping.

‘Category effects on color perception. (a) Categorical sensitivity. The diagram shows how the sensitivity to color differences changes across hue. The x-axis corresponds to hue in DKL color space, and the y-axis to discrimination thresholds. Adapted from Witzel & Gegenfurtner (2013). Note that the green-blue boundary is unlike the others in that it coincides with a local minimum of discrimination thresholds. (b) Categorical facilitation. The bars along the x-axis of the main graphic correspond to color pairs that are composed of the colors illustrated by the inset. The y-axis of the main graphic represents response times in speeded discrimination. Note that discriminating the color pair BC, in which B and C belong to different categories (i.e., red and brown), is fastest even though the distances between colors control for sensitivity to color differences. Adapted from Witzel & Gegenfurtner (2016). Abbreviation: DKL, Derrington-Krausfopf- Lennie. ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.’

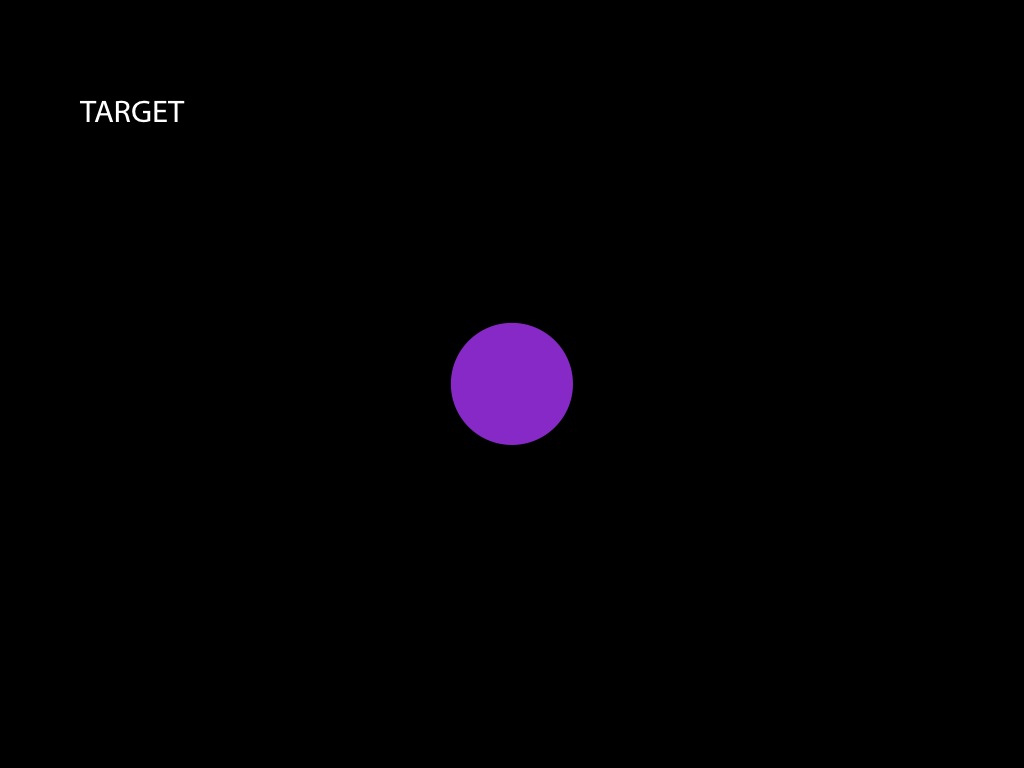

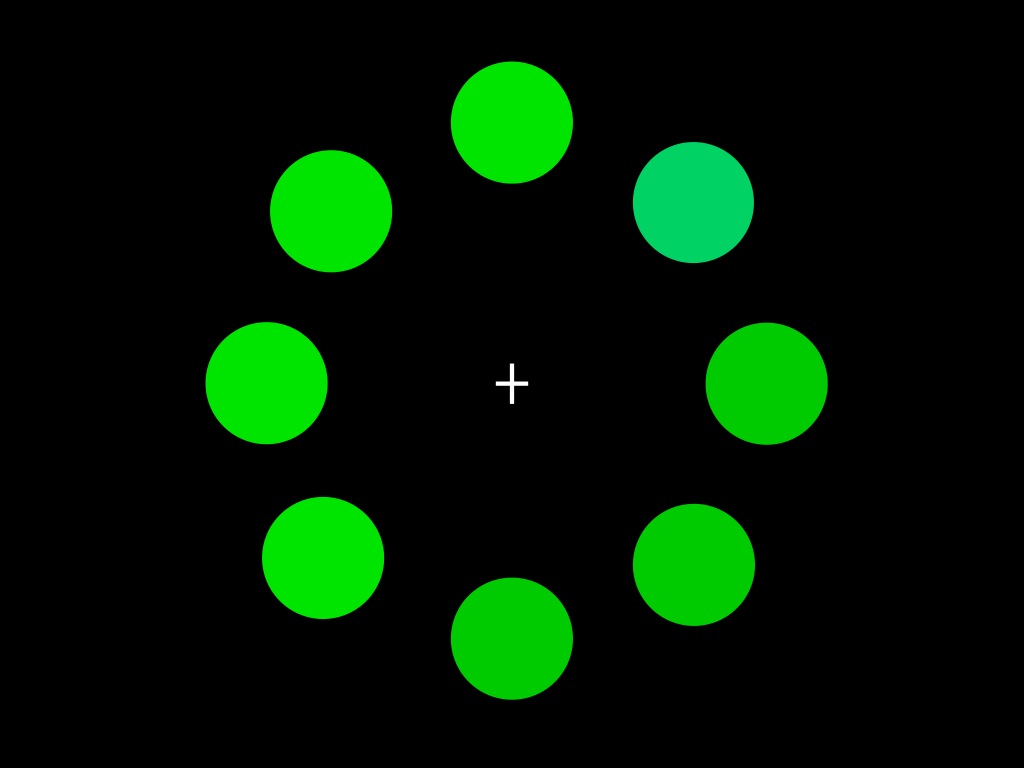

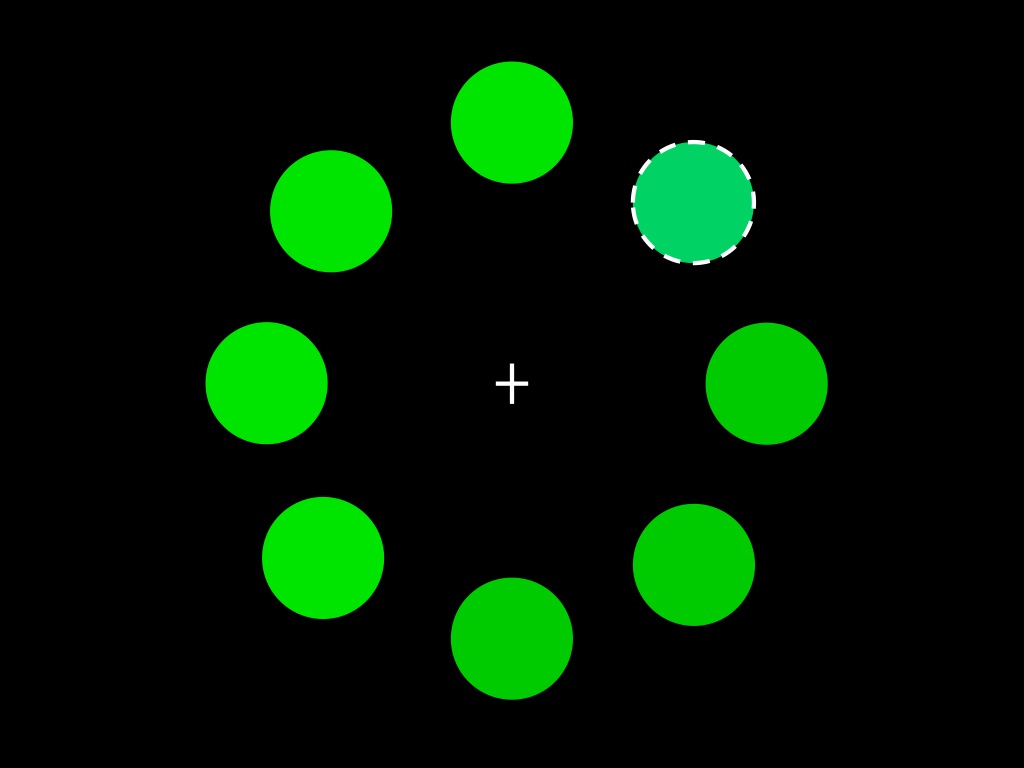

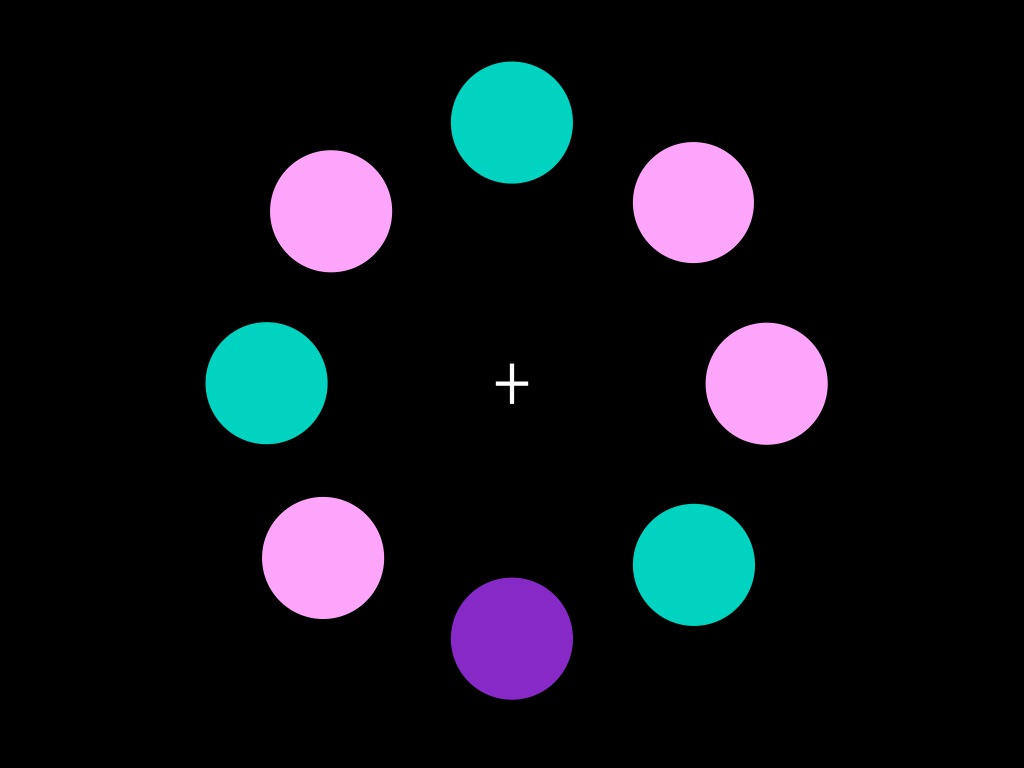

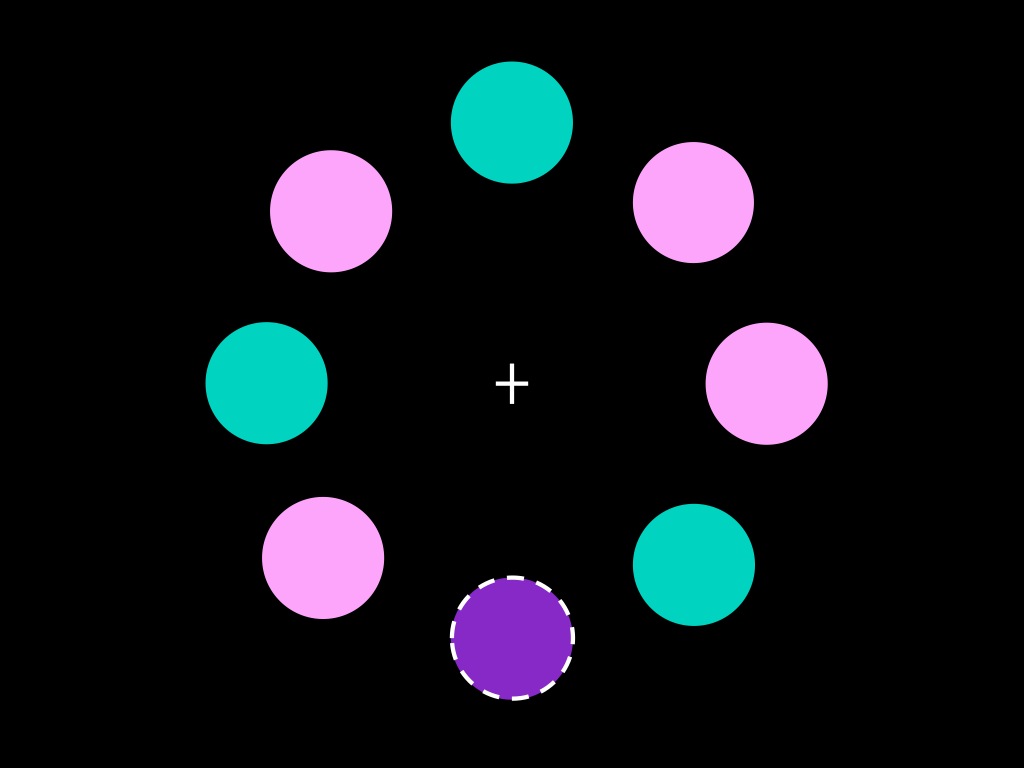

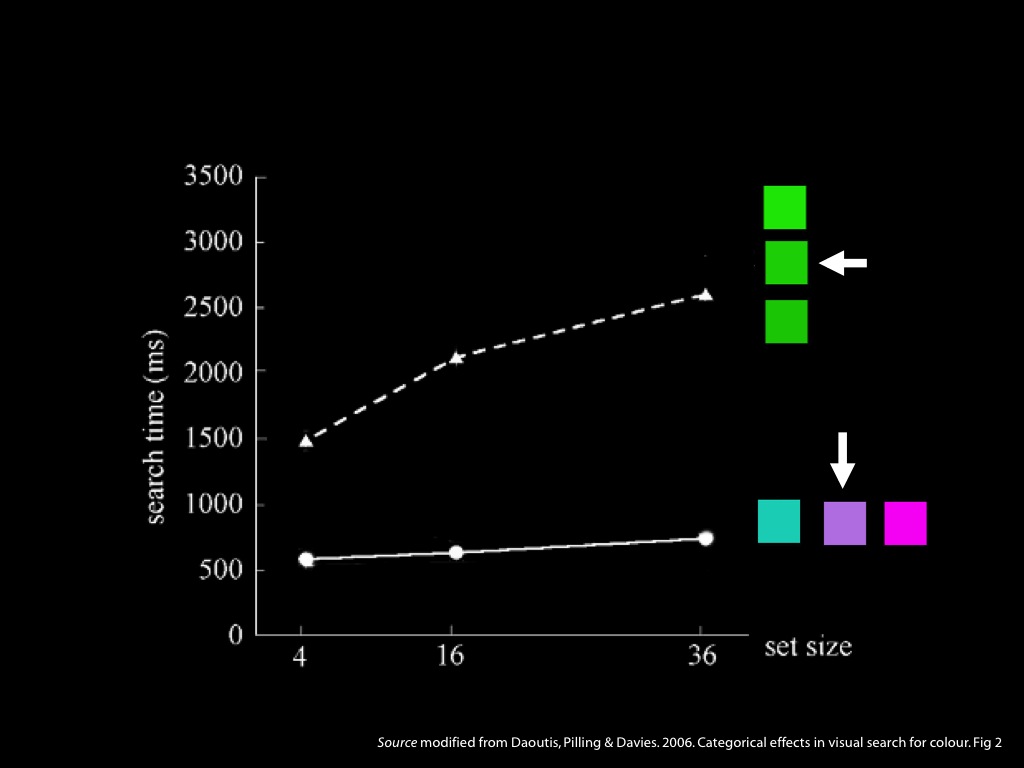

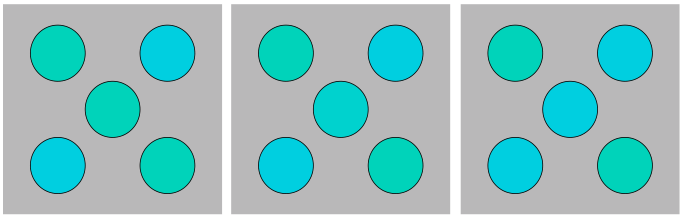

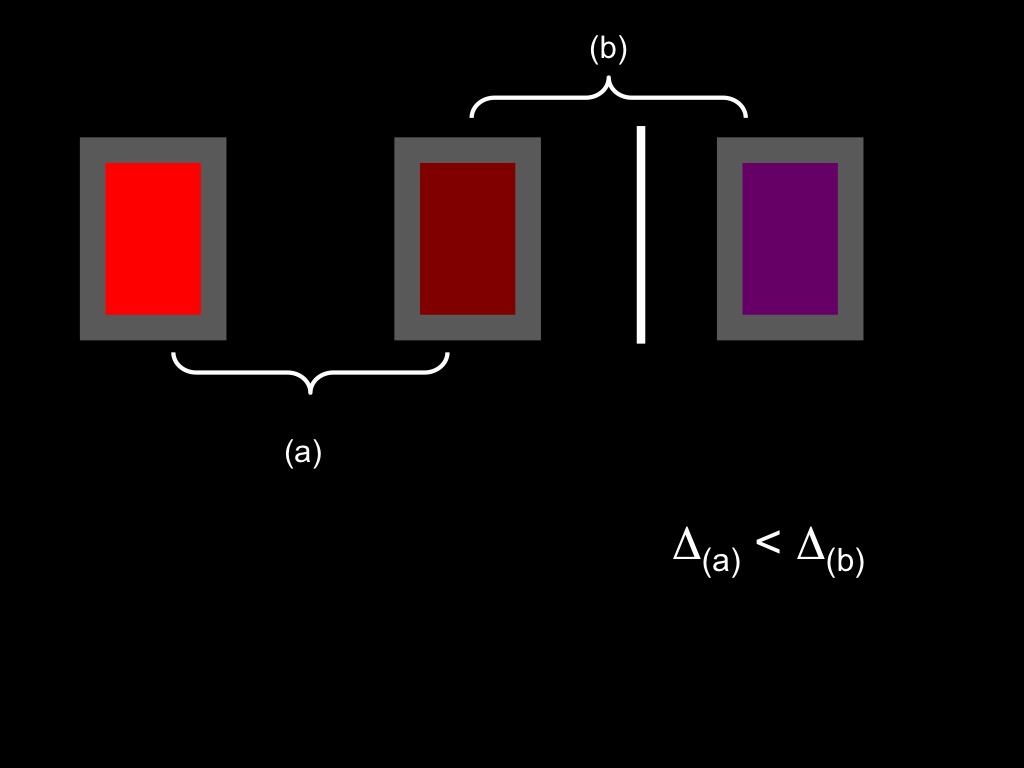

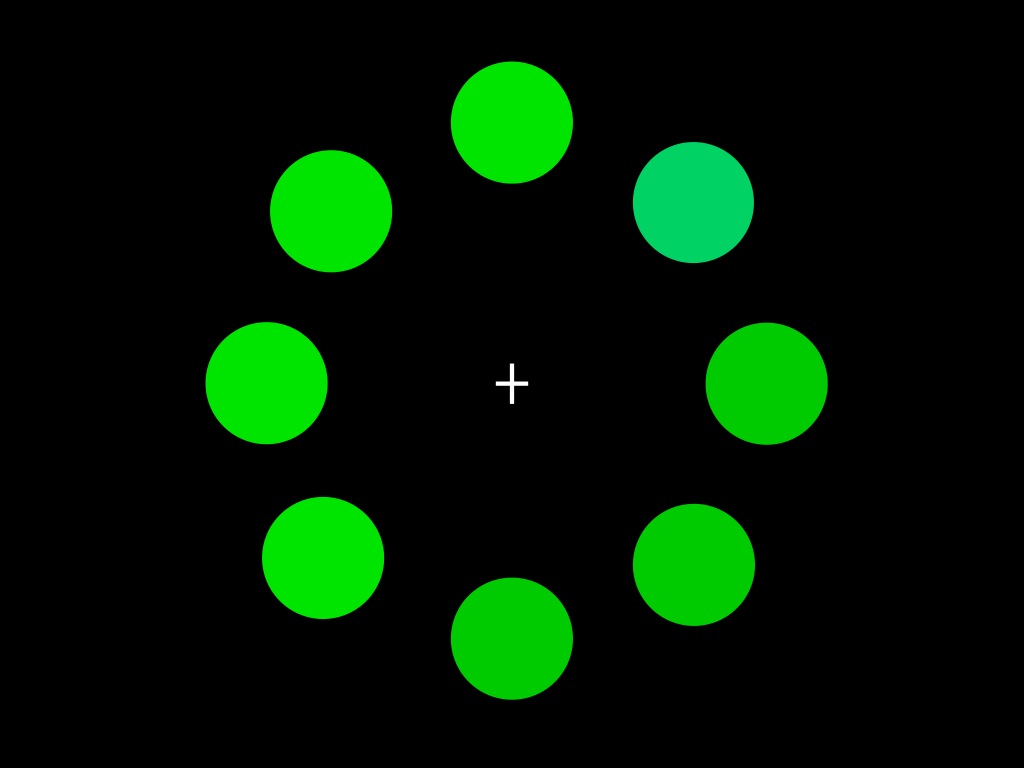

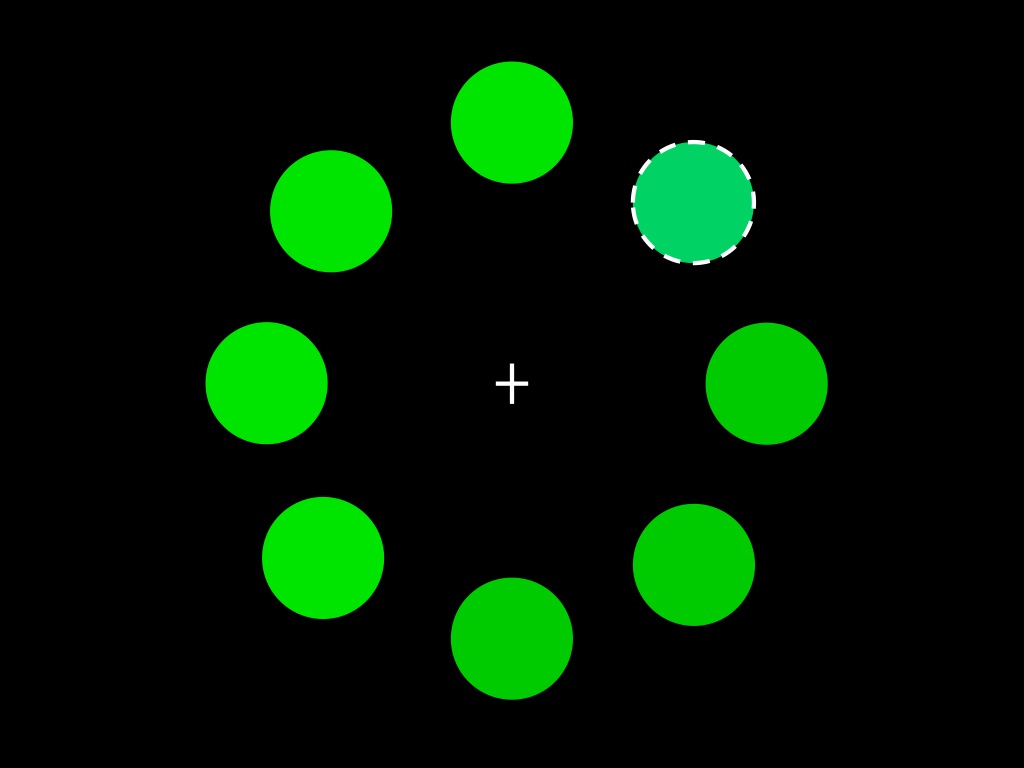

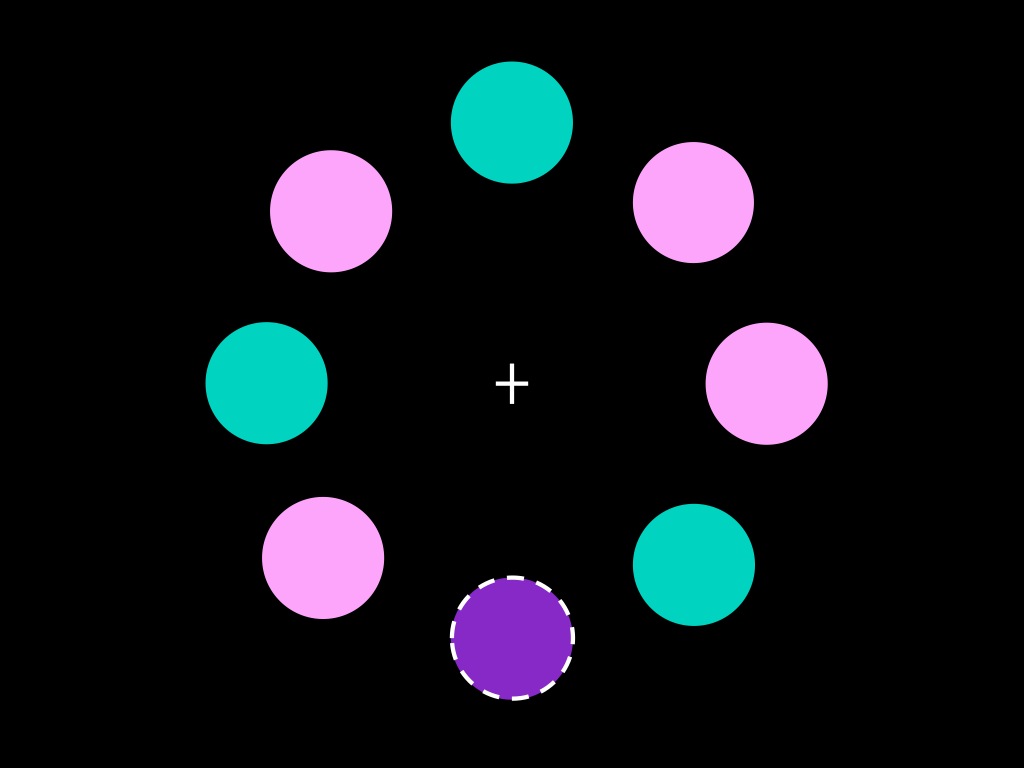

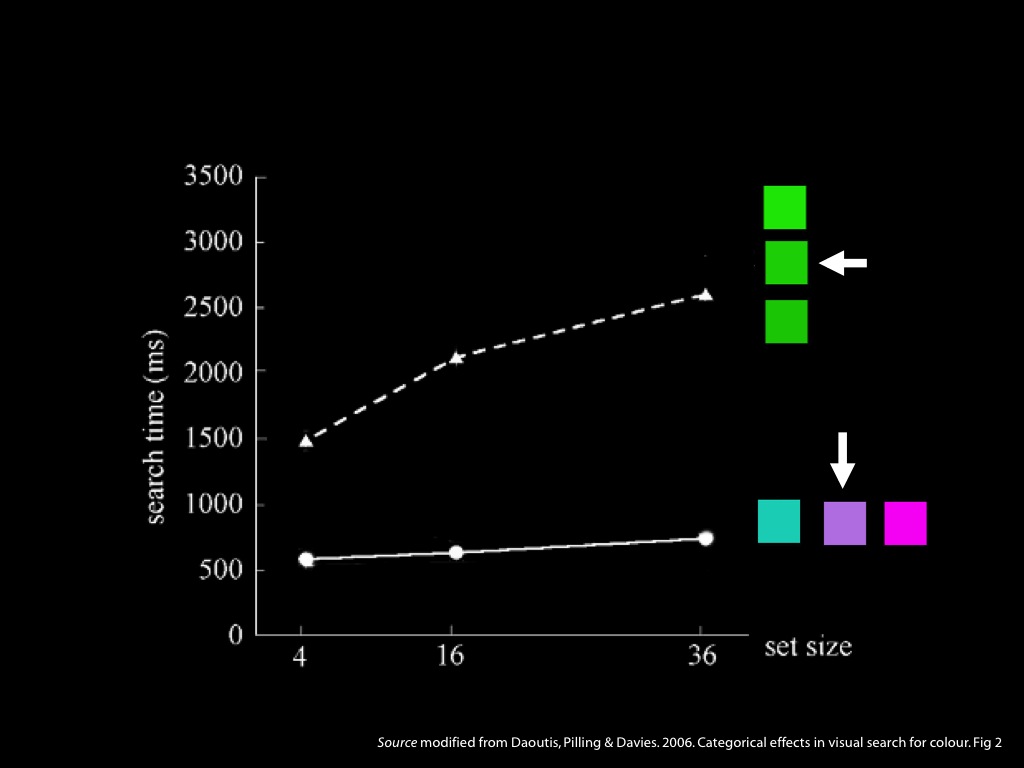

Another measure on which the green sequence differs from the blue-pink-purple sequence is pop-out, which is defined operationally in terms of visual search tasks \citep[p.\ 117]{Treisman:1986pm}.

First I need to explain what a visual search task is.

In visual search tasks tasks, subjects are shown an array of objects and asked to identify the one with a certain property.

For example, one might be shown an array of twenty animal pictures and asked to identify the cat.

Normally the time it takes subjects to find a target increases linearly as the number of objects in the array increases.

But when the target of a visual search is defined in terms of colour and the colours of the distractors are categorically different from the colour of the target, subjects can find the target just as quickly when it is in among 36 distractors as when there are only four distractors \citep[Experiment 1]{Daoutis:2006qk}.

This is, the colours pop out.

\textbf{pop-out} ‘Such targets pop out of the display, so that the time it takes to find them is independent of the number of distractors’ \citep[p.\ 117]{Treisman:1986pm}.

When target and distractors differ in colour category there can be pop-out effects \citep{Daoutis:2006qk}.

visual search task

\begin{center}

\includegraphics[scale=0.25]{img/categorical_colour_difference3.jpg}

\end{center}

Hypothesis: Red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things.

1. Redness will influence discrimination.

2. Redness will influence similarity judgements.

3. Redness will influence pop-out effects.

4. Redness will influence perceptual grouping.

‘Category effects on color perception. (a) Categorical sensitivity. The diagram shows how the sensitivity to color differences changes across hue. The x-axis corresponds to hue in DKL color space, and the y-axis to discrimination thresholds. Adapted from Witzel & Gegenfurtner (2013). Note that the green-blue boundary is unlike the others in that it coincides with a local minimum of discrimination thresholds. (b) Categorical facilitation. The bars along the x-axis of the main graphic correspond to color pairs that are composed of the colors illustrated by the inset. The y-axis of the main graphic represents response times in speeded discrimination. Note that discriminating the color pair BC, in which B and C belong to different categories (i.e., red and brown), is fastest even though the distances between colors control for sensitivity to color differences. Adapted from Witzel & Gegenfurtner (2016). Abbreviation: DKL, Derrington-Krausfopf- Lennie. ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.’

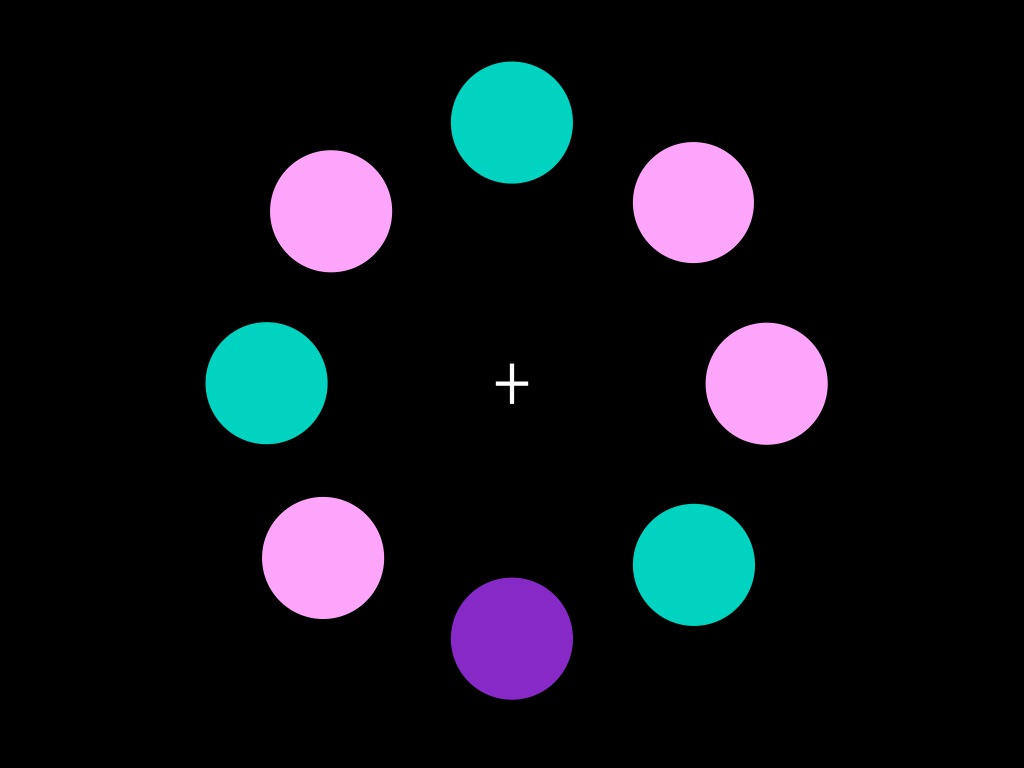

Webster & Kay 2012, figure 1

Converging evidence that things labelled with different basic colour terms

do not thereby differ in visual appearance involves a third method for

detecting visual appearances (\citealp{webster:2012_color}). The idea, as

illustrated in Figure \vref{fig:perceptual_grouping}, is that how things

appear with respect to colour should influence how likely it is that they

will be grouped together perceptually. The results are consistent with the

view that whether objects are labelled with the same basic colour term

makes no measurable difference to how they are grouped perceptually. This

further supports suspicion that properties denoted by colour terms like

‘red’ make no difference to visual appearances (see also

\citealp{davidoff:2012_perceptual}).

Let’s consider the experiment in more detail.

‘circles at opposite diagonal corners of the square had the same color,

while the two diagonals differed in color by a fixed angle of 30°’.

The center circle could either be the same colour as one of the diagonals

(as in the left and right panels),

or it could be an inbetween colour (as in the middle panel).

When the central colour is the same as one of the diagonals, you should perceptually

group the diagonal as a line, like \/ or \\.

Subjects’ task was indeed to judge which way the diagonal went.

\citet{webster:2012_color} varied the center colour to find at what point

a given subject was equally like to judge that the line was \/ or \\.

Call this the ‘grouping midpoint colour’.

(p. 378: ‘Observers made a two-alternative forced choice response to indicate

whether the perceived orientation was clockwise or counterclockwise. A

staircase varied the center color angle to estimate the an- gle at which

both orientations appeared equally likely, with the point of subjective

equality estimated from the mean of the final 10 of 13 reversals in the

staircase.’)

Webster & Kay 2002, figure 2

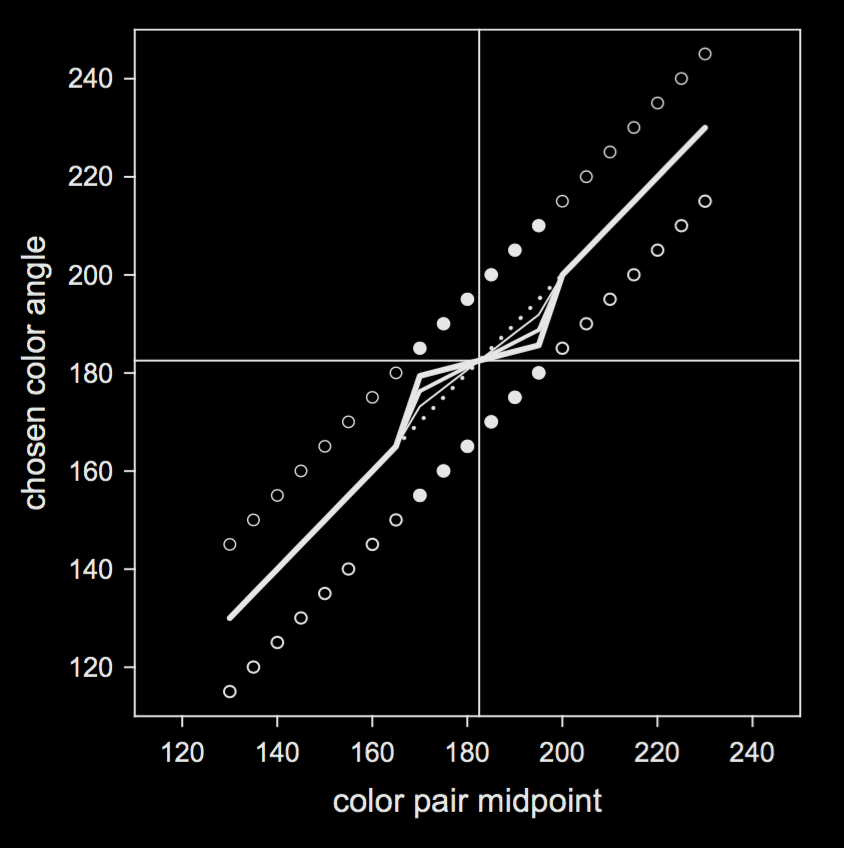

\citet{webster:2012_color} reasoned like this:

\begin{enumerate}

\item Where the two diagonals are from within the same colour category,

the grouping midpoint colour should be the midpoint in a colour space that

represents retinal colour discrimination.

\item Where the two diagonals are from different colour categories (one is

green, the other is blue), and one of the diagonals is just over a boundary,

then the grouping midpoint colour should be closer to the colour of the diagonal

that is just over the boundary in a colour space that

represents retinal colour discrimination.

\end{enumerate}

This prediction is illustrated in the figure.

The dotted line shows the prediction if there is no effect of colour category

on perceptual grouping; the solid lines show different strengths of effect.

They found that almost no indicators of an

effect of colour category on perceptual grouping

(there are a variety of measures and one was signifiant:

p. 381: ‘the participants’ settings thus trended toward a (very weak) CP effect,

with an average bias of 0.10 (which was nevertheless significantly differ-

ent from zero; t (7) = 3.73, p < .01).’).

They also suggested that these effects may be due to the use of

CIELAB as a colour space

(p. 382: ‘ the small biases we found in the observer’s settings may in part

include an artifact of the stimulus space, weakening further the evidence for a

clear CP effect in the grouping task.’)

\begin{center}

\includegraphics[scale=0.25]{img/categorical_colour_difference3.jpg}

\end{center}

Hypothesis: Red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things.

1. Redness will influence discrimination.

2. Redness will influence similarity judgements.

3. Redness will influence pop-out effects.

4. Redness will influence perceptual grouping.

‘Category effects on color perception. (a) Categorical sensitivity. The diagram shows how the sensitivity to color differences changes across hue. The x-axis corresponds to hue in DKL color space, and the y-axis to discrimination thresholds. Adapted from Witzel & Gegenfurtner (2013). Note that the green-blue boundary is unlike the others in that it coincides with a local minimum of discrimination thresholds. (b) Categorical facilitation. The bars along the x-axis of the main graphic correspond to color pairs that are composed of the colors illustrated by the inset. The y-axis of the main graphic represents response times in speeded discrimination. Note that discriminating the color pair BC, in which B and C belong to different categories (i.e., red and brown), is fastest even though the distances between colors control for sensitivity to color differences. Adapted from Witzel & Gegenfurtner (2016). Abbreviation: DKL, Derrington-Krausfopf- Lennie. ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.’

Do red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things?

So do red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things?

As far as we know: No!

While doubts might be raised about the details of one or another method, the

overall pattern is clear: the most careful attempts to find differences in

appearance associated with properties denoted by colour terms like ‘red’ have

all failed.

To reject this conclusion, we would have to insist that differences in

appearance exist but influence neither judgements of perceptual similarity nor

perceptual grouping and so are too subtle to detect.

This is certainly possible, but it seems wrong simply to insist that it is correct.

Whether colour terms like ‘red’ denote properties of objects that are

presented in visual experience is something best decided experimentally, not

introspectively; and, as far as we know, they do not.

\section{Why Do Some Claim to Visually Experience Red?}

Suppose, as argued, it is untrue that humans visually experience red or any

other categorical colour properties.

Why have so many philosophers have assumed the opposite, and done so without argument?

Suppose, as argued, it is untrue that humans visually experience red or any

other categorical colour properties.

Why have so many philosophers have assumed the opposite, and done so without argument?

Some time after learning to use a colour term like ‘red’

somewhat accurately, humans become faster and more accurate at

distinguishing things which differ in whether they have the property

denoted by that colour term (faster: \citealp{Bornstein:1984cb}; more

accurate: \citealp[p.\ 22--7]{Roberson:1999rk}; not usually immediately:

\citealp{Franklin:2005hp}). In fact, methods highly similar to those which

indicate the absence of appearances do reveal that these properties affect

speed and accuracy of discrimination (\citealp{witzel:2014_categorical}).

As discrimination of these colour properties depends on pre-attentive

processes which are automatic in some of the senses that perceptual

processes are \citep{Daoutis:2006ij,clifford_color_2010}, the abilities to

discriminate may intuitively give rise to the impression that properties

like \emph{red} affect how things appear.

‘If someone with normal color vision looks at a tomato in good light,

the tomato will appear to have a distinctive property—a property that

strawberries and cherries also appear to have, and which we call ‘red’ in

English’

(Byrne & Hilbert 2003, p. 4)

Recall the argument.

What we have established does not necessarily contradict the first premise.

It may contridict the last premise

1. The second sequence of sensory encounters, (b),

differ from each other more in phenomenal character than the first sequence of sensory encounters,

(a), differ from each other.

2. This difference in differences in phenomenal character is a fact in need of explanation.

3. The difference cannot be fully explained by appeal only to perceptual experiences as of particular shades.

4. The difference can be explained in terms of perceptual experiences as of categorical colour properties.

5. There is no better explanation of the difference.

I want to have a go at rejecting the fifth premise without rejecting the first premise ...

As I said, I want to have a go at rejecting the fifth premise without rejecting the first premise.

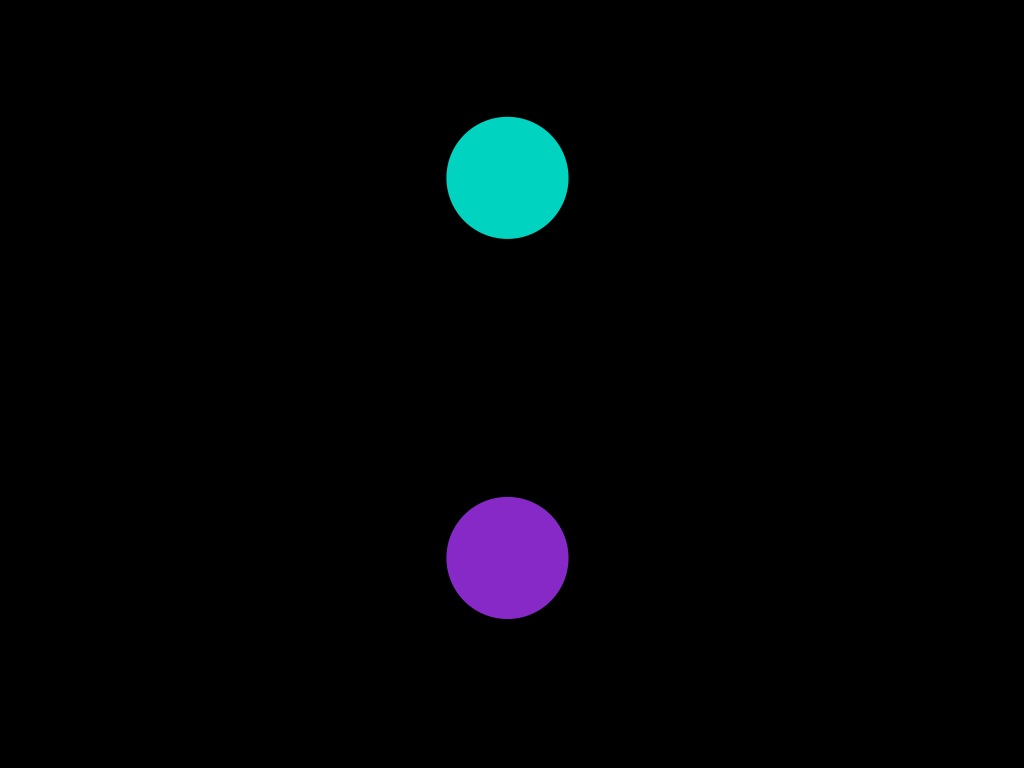

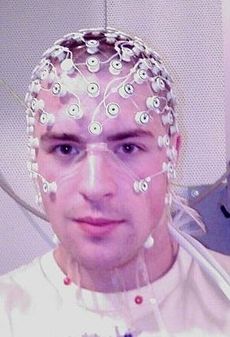

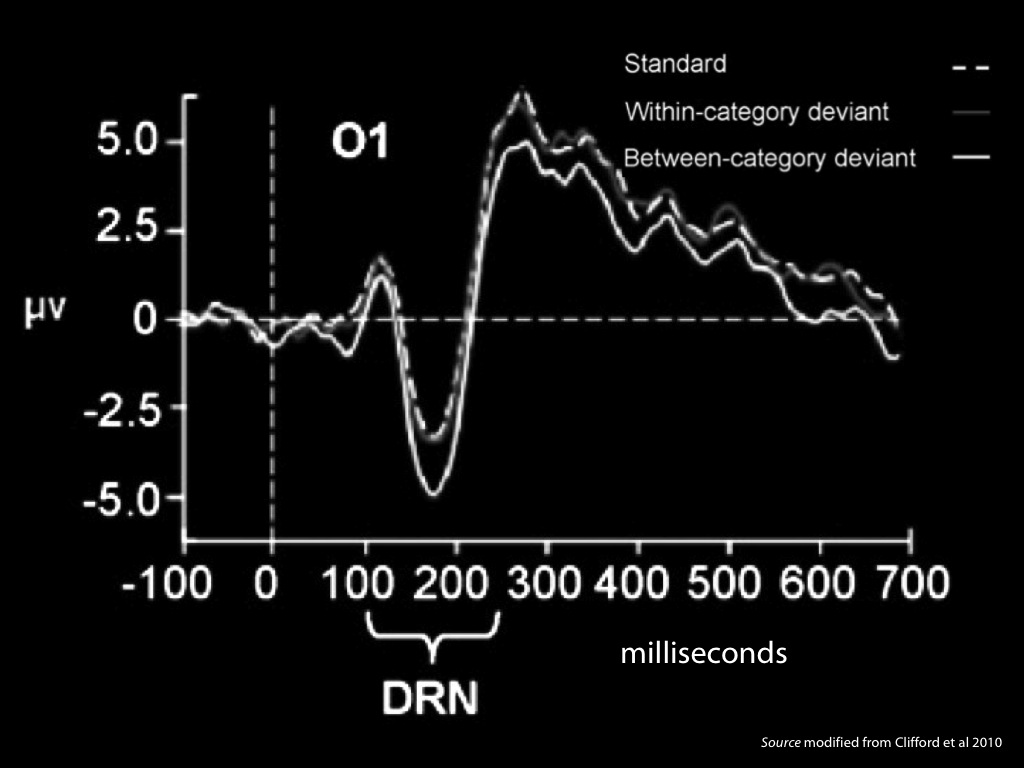

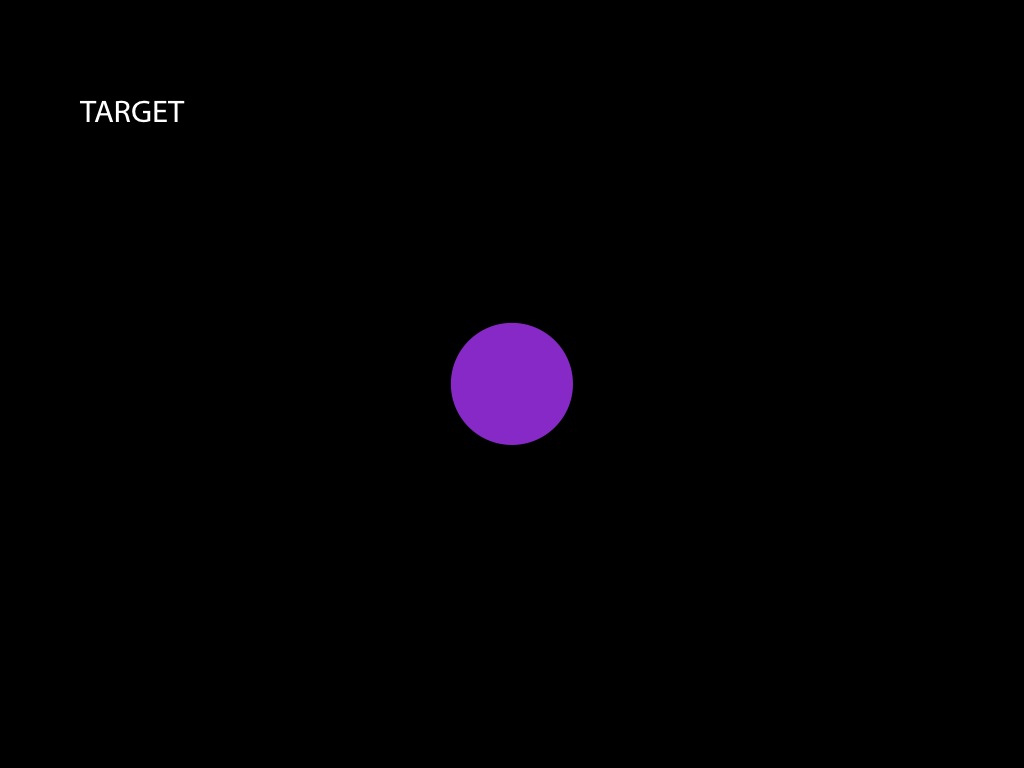

For an example of a category effect which is automatic, I need to introduce you to the odd-ball paradigm.

In the odd-ball paradigm, you see a series of things that are all the same; and then, unpredictably, you see something different.

We can use sensitivity to odd-balls to measure the difference between the two blues and the blue-green pair.

This is useful because odd-ball effects can be detected very early in visual processessing, before attention kicks in.

They allow us to probe automatic processes.

Now suppose we play you an odd ball sequence.

We want to know whether an automatic process picks up on the difference.

And we want to know whether the automatic process picks up on the difference always or only when a category change is involved.

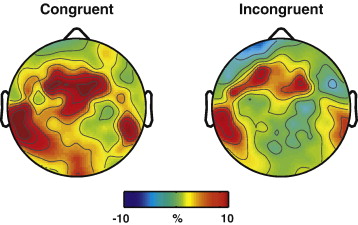

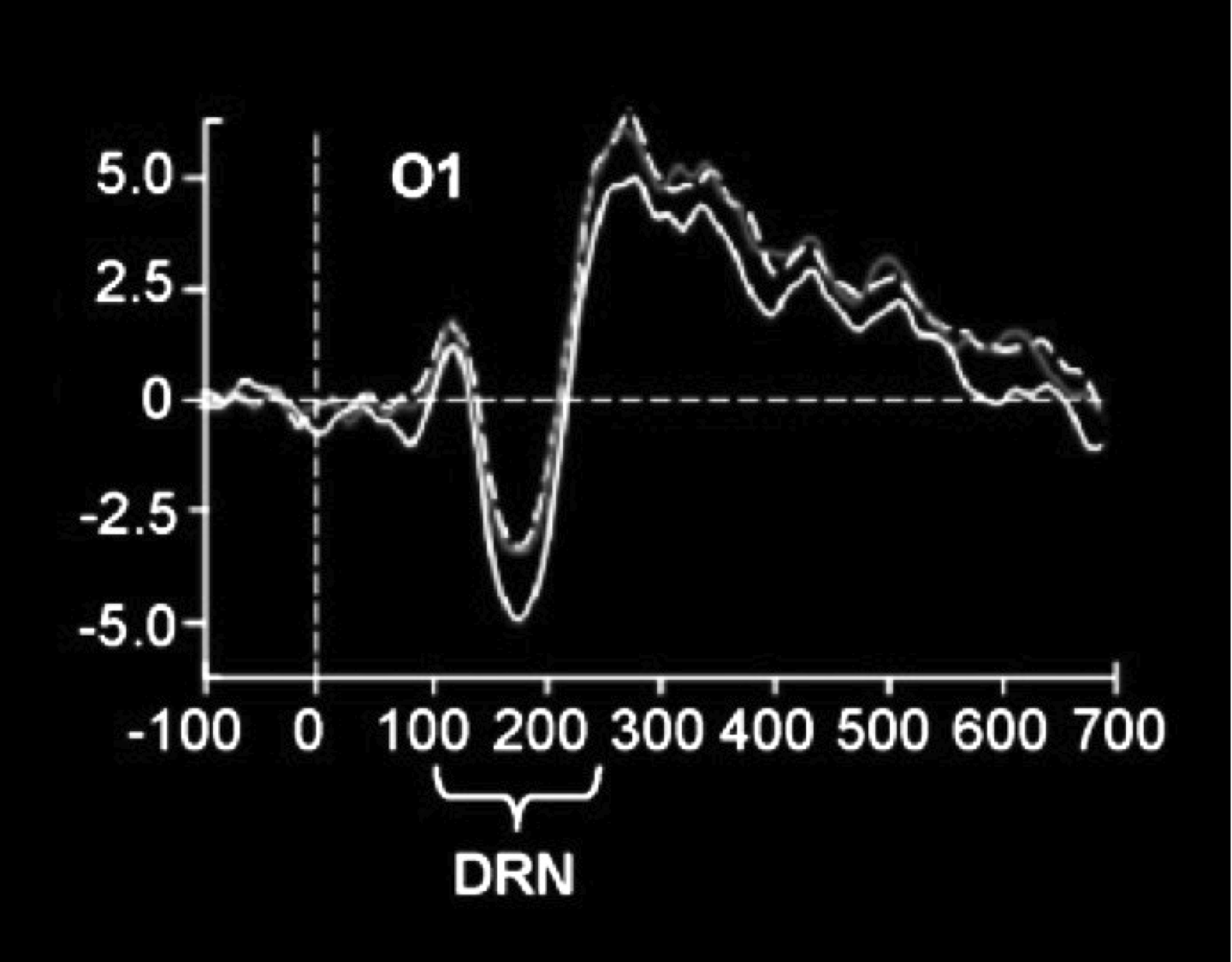

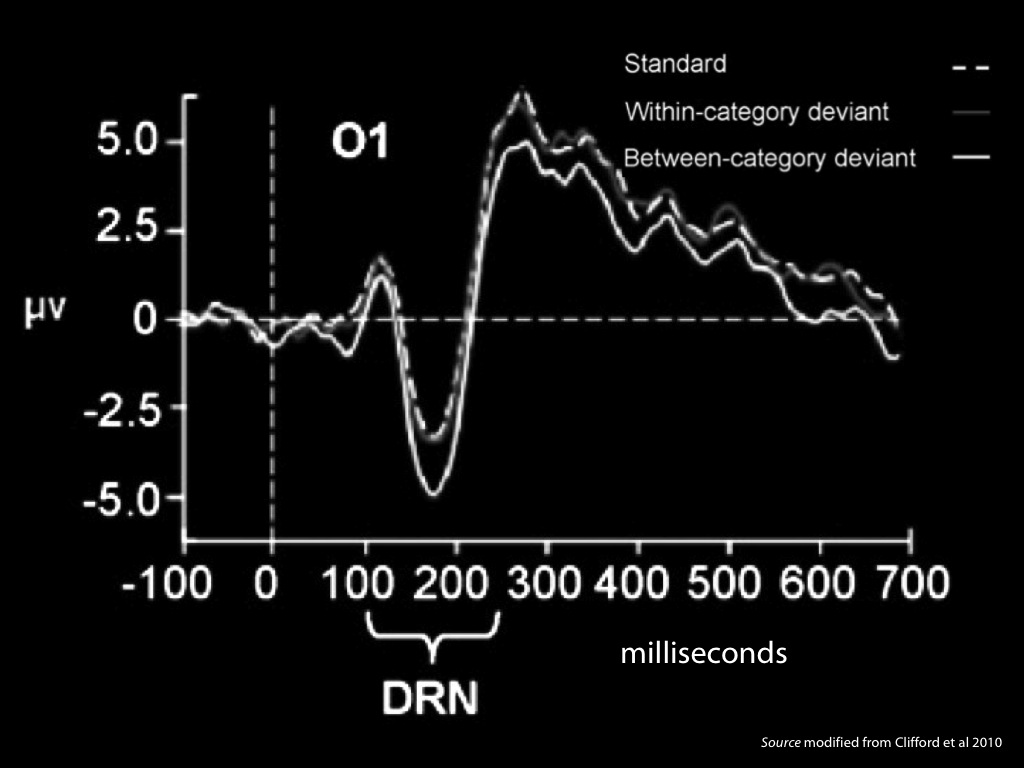

To do this we need to measure an event-related potential called vMMN (which is short for visual mismatch negativity).

vMMN (visual mismatch negativity): an event-related potential thought to index pre-attentive change detection in the visual cortex

Now I need to explain what an event-related potential is.

An ERP like the vMMN stands to an overall EEG measurement a bit like the number 78 bus does to a collection of atoms.

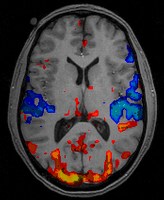

While we're on methods, let's quickly talk about fMRI.

- better spatial resolution

- limited temporal resolution

- subject can't move

So now we know what an event-related potential is, let's get back to the vMMN (visual mismatch negativity).

vMMN (visual mismatch negativity): an event-related potential thought to index pre-attentive change detection in the visual cortex

So let me show you a task that uses this odd-ball effect

Fixate on this cross.

And when you see the rectangle, press the space bar with both index fingers.

That's it.

Except that you also see a block of colour on every trial.

You're instructed to ignore this block of colour.

And generally that's easy because it's always the same colour.

But just occasionally it's a different colour.

In one condition, the usual and odd-ball colours are the blues.

And in the other condition, the usual and odd-ball colours are cross-category, from blue-green.

We're interested in whether there's a sign that your brain has detected the change when the odd ball colour occurs.

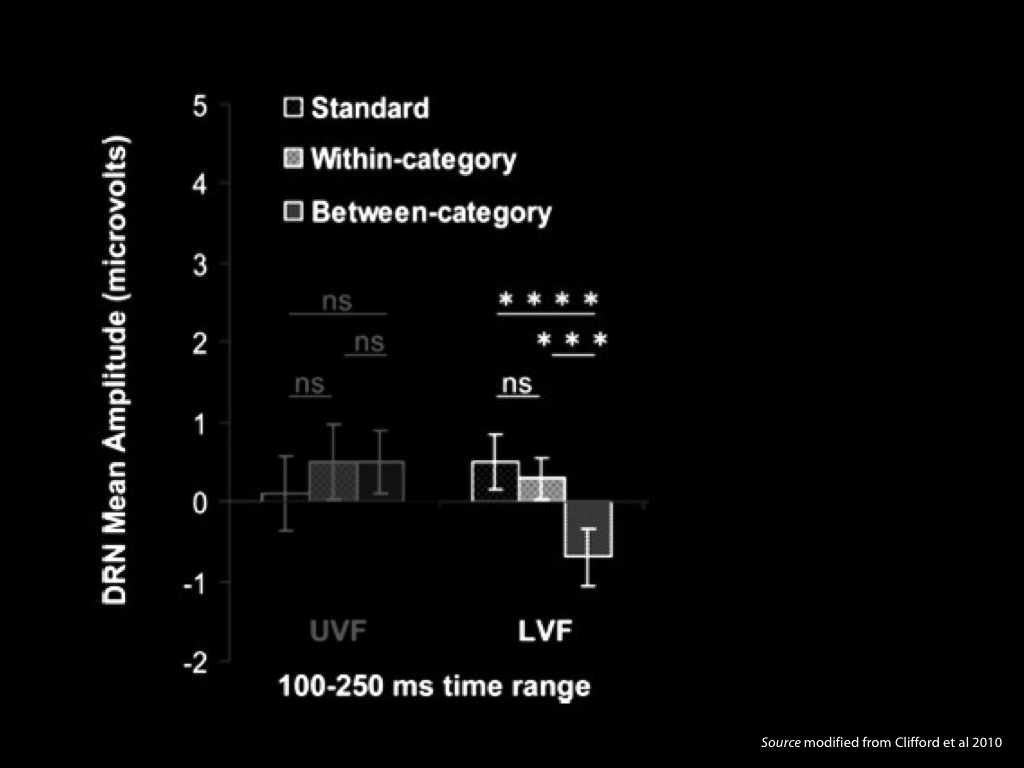

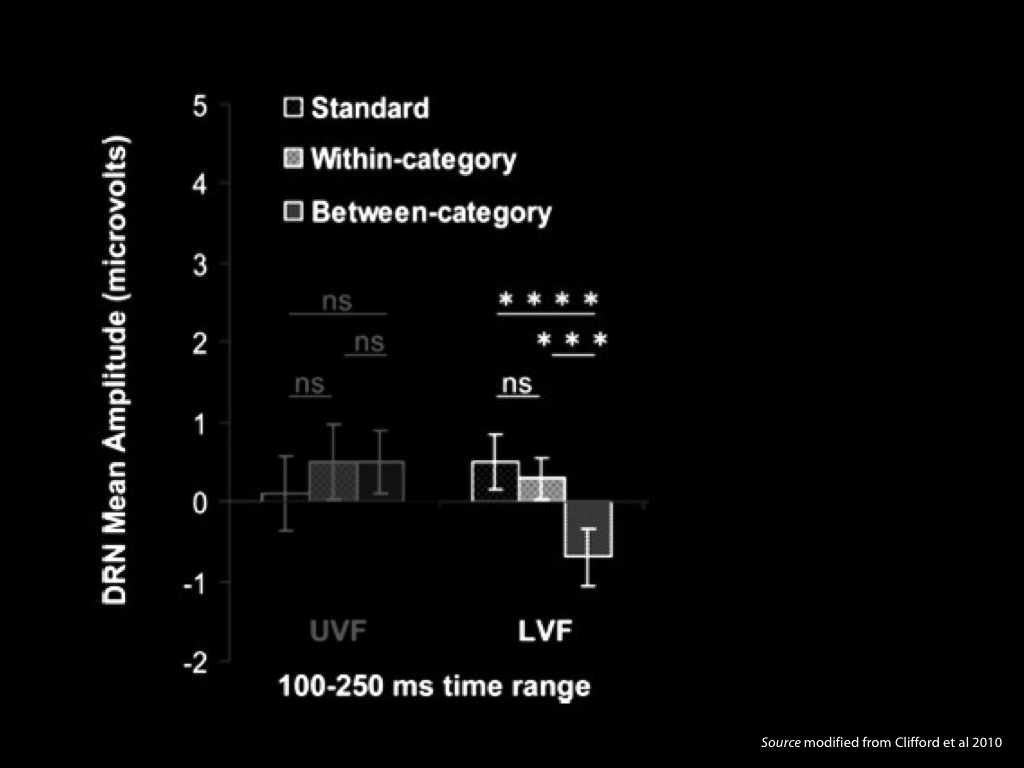

Put roughly, the results show that there is signal of pre-attentive change detection at around 100-200 milliseconds in the left visual field.

This is another way of presenting the same finding.

The vMMN is a DRN, but not all DRNs are vMMNs (see the paper).

Since this study \citep{clifford_color_2010}, \citet{he:2014_color} have challenged

the results arguing that there is no vMMN when you control for irregularities in

colour spaces using JNDs. However \citet{zhong:2015_shortterm} find a vMMN for

newly trained categorical colour properties (which \citep{clifford:2012_neural}) didn’t.

Mastering some colour words leads to

pre-attentive, automatic capacities to disciminate categorical colour properties

corresponding to those words.

Some time after (but not usually immediately after) learning to use a colour term like

‘red’ somewhat accurately, humans become faster and more accurate at

distinguishing things which differ in whether they have the property denoted by

that colour term (faster: \citealp{Bornstein:1984cb}; more accurate:

\citealp[p.\ 22--7]{Roberson:1999rk}; not usually immediately:

\citealp{Franklin:2005hp}). In fact, methods highly similar to those which

indicate the absence of appearances do reveal that these properties affect

speed and accuracy of discrimination (\citealp{witzel:2014_categorical}). As

discrimination of these colour properties depends on pre-attentive processes

which are automatic in some of the senses that perceptual processes are

\citep{Daoutis:2006ij,clifford_color_2010}, the abilities to discriminate may

intuitively give rise to the impression that properties like \emph{red} affect

how things appear.

How?

How?

How could these pre-attentive, automatic abilities to discriminate

give rise to the impression that properties like \emph{red} affect

how things appear?

Option 1: sensations

Option 1: The processes of discrimination modulate the overall phenomenal

character of experience, and do so differently depending on which

categorical colour properties are discriminated.

On this option, we have something like a phenomenal signal of sameness and

difference.

Option 2: misinterpretation

“Discriminable wavelengths seem to be categorized together because they appear

perceptually similar”

(Bornstein 1987: 288-9).

Option 2: Philosophers (and perhaps others) intuitively (and incorrectly) assume that

capacities to discriminate depend on how things visuall appear.

That is, the intuitive (and incorrect) assumption is that

I can visually distinguish categorical properties because things

visually appear to have those categorical colour properties.

(Compare \citep[pp.~288--9]{Bornstein:1987vv}:

“Discriminable wavelengths seem to be categorized together because they appear perceptually similar”.)

Appendix: Do you visually experience red because you call things ‘red’?

\section{Appendix: Do you visually experience red because you call things ‘red’?}

“surprising it would be indeed if I have a perceptual experience as of red

because I call the perceived object ‘red’”

(Stokes 2006, pp. 324--5).

“surprising it would be indeed if I have a perceptual experience as of red because I call the perceived object ‘red’.”

\citep[pp.~324--5]{Stokes:2006fd}.

(Stokes 2006, pp. 324--5)

Stokes makes this observation in passing. I want to show

that what Stokes finds so suprising is true, or would be if it were true that

red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things.

Stokes has formulated things badly here.

The important thing isn’t the particular word I use, ‘red’ vs, say, ‘rot’,

‘rosso’ or ‘rose’.

Rather it’s that I have a label for the perceived object which I also

use for all the things that have the property red.

Argument:

\begin{enumerate}

\item Red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things.

\item The capacity to detect the difference in visual appearance between

red and non-red things is, or depends on, the capacity to visually

discriminate red and non-red things.

\item The capacity to visually discriminate red and non-red things depends

on the capacity to label the red things (for example, using ‘red’).

\end{enumerate}

Therefore:

\begin{enumerate}[resume]

\item I have a perceptual experience as of red span.italic

because span I call the perceived object ‘red’.

\end{enumerate}

1. Red things differ in visual appearance from non-red things.

[assumption]

2. The capacity to detect the difference in visual appearance between

red and non-red things

is, or depends on,

the capacity to visually discriminate red and non-red things.

[unargued premise]

3. The capacity to visually discriminate red and non-red things

depends on

the capacity to label the red things (for example, using ‘red’).

[discovery]

It turns out that

the ability to discriminate properties denoted by particular colour terms like

‘red’ depends not only on having learned to use those very terms accurately in

the past \citep{Ozgen:2002yk,Winawer:2007im,zhou:2010_newly} but also on being

able to activate some component of the ability to apply the colour term at the

time a stimulus is presented

\citep{Roberson:2000ge,Pilling:2003bi,Wiggett:2008xt}. % page refs: (Roberson,

Davies and Davidoff 2000: 985; Pilling, Wiggett, et al. 2003: 549-50; Wiggett

and Davies 2008)

Someone who accepts that there are visual experiences as of

\emph{red} must either suppose that these experiences are only indirectly

related to abilities to discriminate or else accept the surprising idea that

such visual experiences are a consequence of covert labelling. This dilemma can

be avoided by rejecting the subject-determining platitude and with it the

existence in humans of visual experiences as of \emph{red}.

Therefore:

4. I have a perceptual experience as of red because I call the perceived object ‘red’.

Should we reject this ...

conclusion

Red things do not differ in visual appearance from non-red things in virtue of their redness.