Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

06: Decision Theory and Habitual Processes

\def \ititle {06: Decision Theory and Habitual Processes}

\begin{center}

{\Large

\textbf{\ititle}

}

\iemail %

\end{center}

\section{Decision Theory}

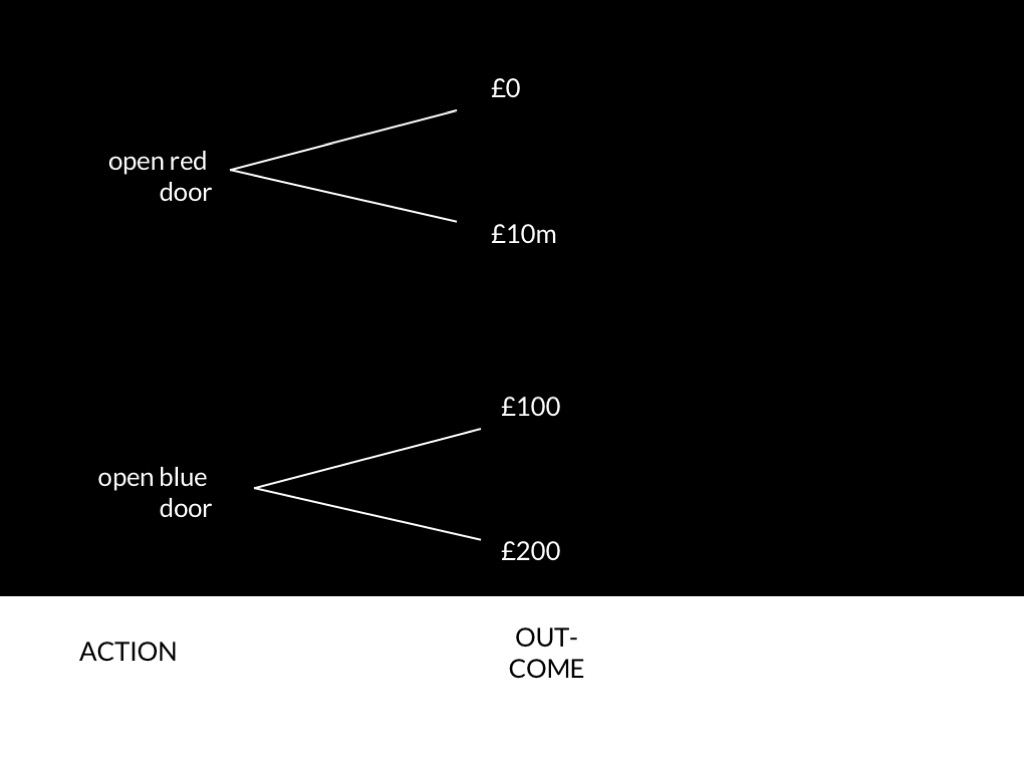

How do rational agents decide which of several available actions to perform?

How do rational agents decide which of several available actions to perform?

How do rational agents decide which of several available actions to perform?

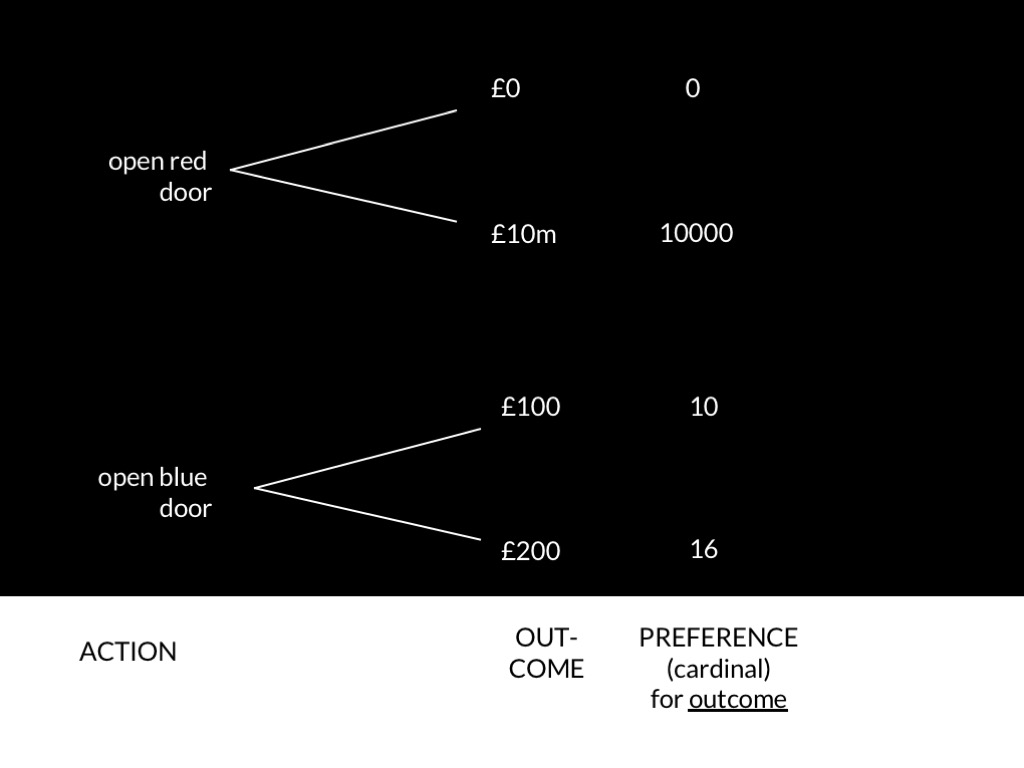

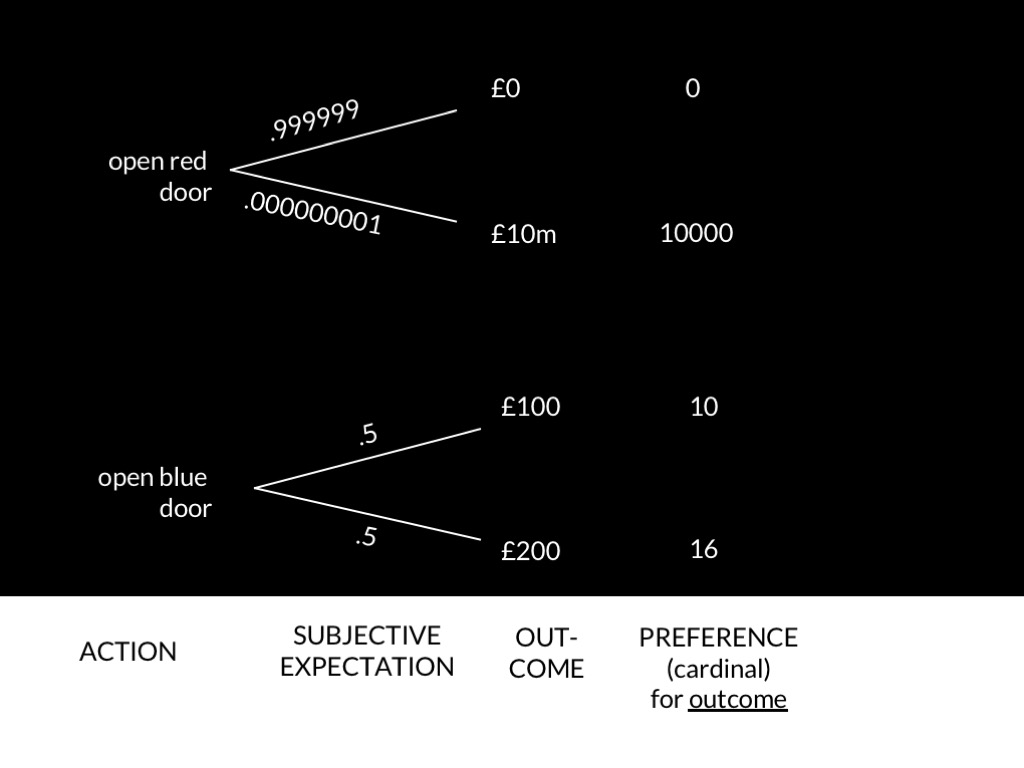

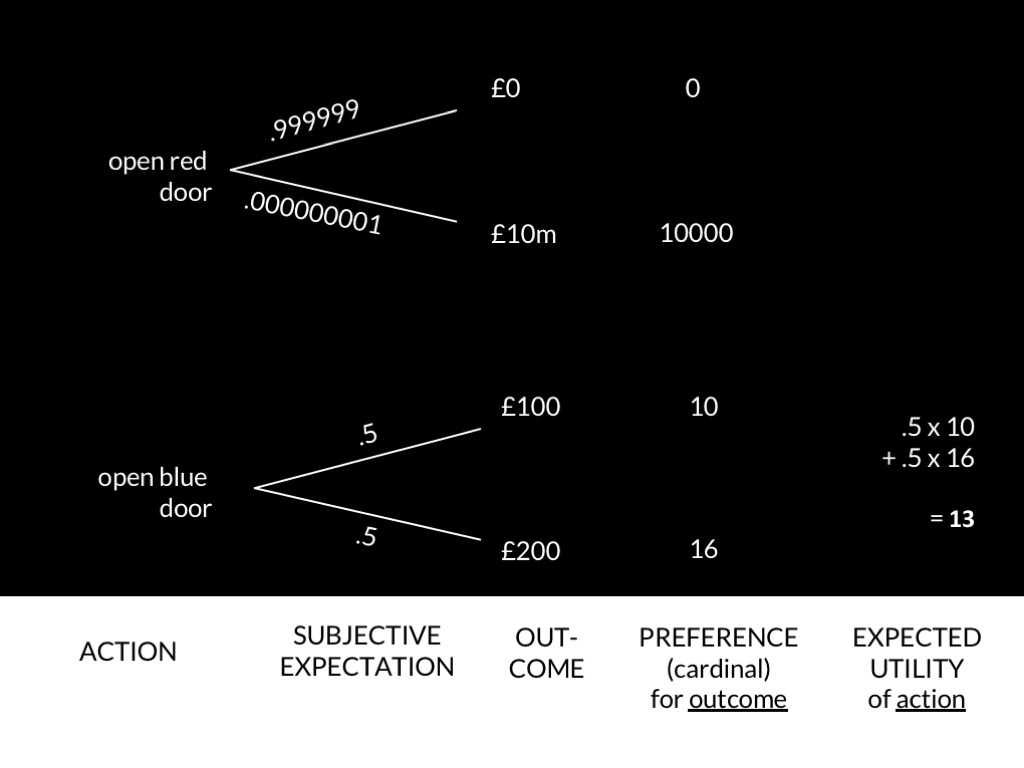

How you act

is a function of two things:

your preferences concerning various outcomes

and your beliefs about how likely an available action is to satisfy each of your preferences.

This is important for linking decision theory with belief-desire.

‘we should think of meanings and beliefs as interrelated constructs of a single theory just

as we already view subjective values and probabilities as interrelated constructs of decision theory’

\citep[p.~146]{Davidson:1974gh}

Davidson, 1974 p. 146

\section{Game Theory}

A game is ‘any interaction between agents that is governed by a set of rules

specifying the possible moves for each participant and a set of outcomes for each possible combination of moves’

(Hargreaves and Varoufakis, 2004 p. 3)

The Roots, 2006

A game is ‘any interaction between agents that is governed by a set of rules

specifying the possible moves for each participant and a set of outcomes for each possible combination of moves’

(Hargreaves and Varoufakis, 2004 p. 3)

Aim: describe rational behaviour in social interactions

Wouldn’t it be cool if we had a way of saying, for any situation, how interacting rational agents would act?

Suppose we could specify a general recipe which would tell us,

for any situation at all, which actions rational agents would

perform. Wouldn’t that be useful to understanding social interactions?

‘we wish to find the mathematically complete principles which define “rational behavior” for the participants in a social economy, and to derive from them the general characteristics of that behavior’

\citep[p.~31]{neumann:1953_theory}

von Neumann & Morgenstern, 1953 p. 31

Here is a very simple situation in which you face a choice.

Assuming you prefer £10 to £10, I can predict which box you will open.

Alternatively, observing which box you open will tell me whether you prefer

to have £10 or £0.

(significance [for later]: Revealed Preference interpretation)

| | me |

| | put £10

in box A | put £10

in box B |

| you | open box A | £10

£0 | £0

£0 |

| open box B | £0

£0 | £10

£0 |

But now consider this situation.

Here it is not just your choice that determines the outcome, but also mine.

But you don’t have an information about what I will do.

So now there’s nothing for you to do but pick a box at random.

The tacit assumption is that I am getting nothing no matter what I do.

But suppose we change the game slightly ... suppose you offer me

£2 to put the money in box A.

Then your situation changes ...

| | me |

| | put £10

in box A | put £10

in box B |

| you | open box A | £8

£2 | £0

£0 |

| open box B | -£2

£2 | £10

£0 |

If I prefer £2 to £0[, and if I am rational, and ...] then I will put the money in box A.

If you know all this, you can predict my action.

And if you can predict my action, you can

rationally choose to open box A.

Let me pause over this.

Suppose that I don’t care about your reward, only my own.

Suppose also that I prefer £2 to £0.

Then regardless of what you do, I should put the money into box A

This is a relatively simple interaction: the outcome my actions bring about for me does not

depend at all on what you do.

By contrast, which outcomes your actions bring about depends on what actions I select.

Note also that it is rational for you to choose box A even if your preferred outcome would be to get £10 rather than £8.

As a rational agent, you want to best satisfy your preferences.

But of course you can’t just follow the money: instead you have to take into account how I am likely to act.

How you act

is a function of two things:

your preferences

and your beliefs about how others will act.

| | Prisoner X |

| | resist | confess |

| Prisoner Y | resist | 3

3 | 0

4 |

| confess | 4

0 | 1

1 |

Consider this profile of actions ...

... you might think that these are the most rational actions to perform

since they give each Prisoner what she most prefers. But note that:

Prisoner X can improve the ouctome by unilaterally deviating from this profile ...

So this is the only nash equilibrium.

How you act

is a function of two things:

your preferences

and your beliefs about how others will act.

The Roots, 2006

A game is ‘any interaction between agents that is governed by a set of rules

specifying the possible moves for each participant and a set of outcomes for each possible combination of moves’

(Hargreaves and Varoufakis, 2004 p. 3)

Aim: describe rational behaviour in social interactions

Wouldn’t it be cool if we had a way of saying, for any situation, how interacting rational agents would act?

Suppose we could specify a general recipe which would tell us,

for any situation at all, which actions rational agents would

perform. Wouldn’t that be useful to understanding social interactions?

‘we wish to find the mathematically complete principles which define “rational behavior” for the participants in a social economy, and to derive from them the general characteristics of that behavior’

\citep[p.~31]{neumann:1953_theory}

von Neumann & Morgenstern, 1953 p. 31

A nash equilibrium for a game

is a profile of actions

from which no agent can unilaterally profitably deviate

see Osborne & Rubinstein, 1994 p. 14; Dixit et al, 2014 p. 95

Let’s see another example

| | Prisoner X |

| | resist | confess |

| Prisoner Y | resist | 3

3 | 0

4 |

| confess | 4

0 | 1

1 |

Consider this profile of actions ...

... you might think that these are the most rational actions to perform

since they give each Prisoner what she most prefers. But note that:

Prisoner X can improve the ouctome by unilaterally deviating from this profile ...

So this is the only nash equilibrium.

| | Gangster X |

| | back

off | fight |

| Gangster Y | back

off | 3

3 | 1

4 |

| fight | 4

1 | 0

0 |

Game Theory

Aim: describe rational behaviour in social interactions.

An action is rational

in a noncooperative game

if it is a member of a nash equilibrium?

Why is the notion of a nash equilibrium so cool? Consider:

How you act

is a function of two things:

your preferences

and your beliefs about how others will act.

Your beliefs about how others will act

are a function of your knowledge of two things:

your beliefs about their preferences

and your beliefs about how they believe others will act.

Your beliefs about how they believe others will act ...

Consider all this complexity.

The notion of a nash equilibrium cuts it out.

It allows us to identify rationally optimal actions in a way that doesn’t

involve working through how these beliefs might be formed.

Or does it?

Decision Theory is about how individuals decide which of several available actions to perform

\citep[textbook:][]{Jeffrey:1983oe}.

Game Theory is a development which focusses on how interacting individuals

select actions when

which outcome one individuals’s action brings about depends on how another acts.

decision theory

How do rational agents decide which of several available actions to perform?

How you act

is a function of two things:

your preferences concerning various outcomes

and your beliefs about how likely an available action is to satisfy each of your preferences.

game theory

When two or more agents interact,

so that which outcome one agent’s choice brings about depends on how another chooses,

how do their preferences guide their choices?

How you act

is a function of two things:

your preferences

and your beliefs about how others will act.

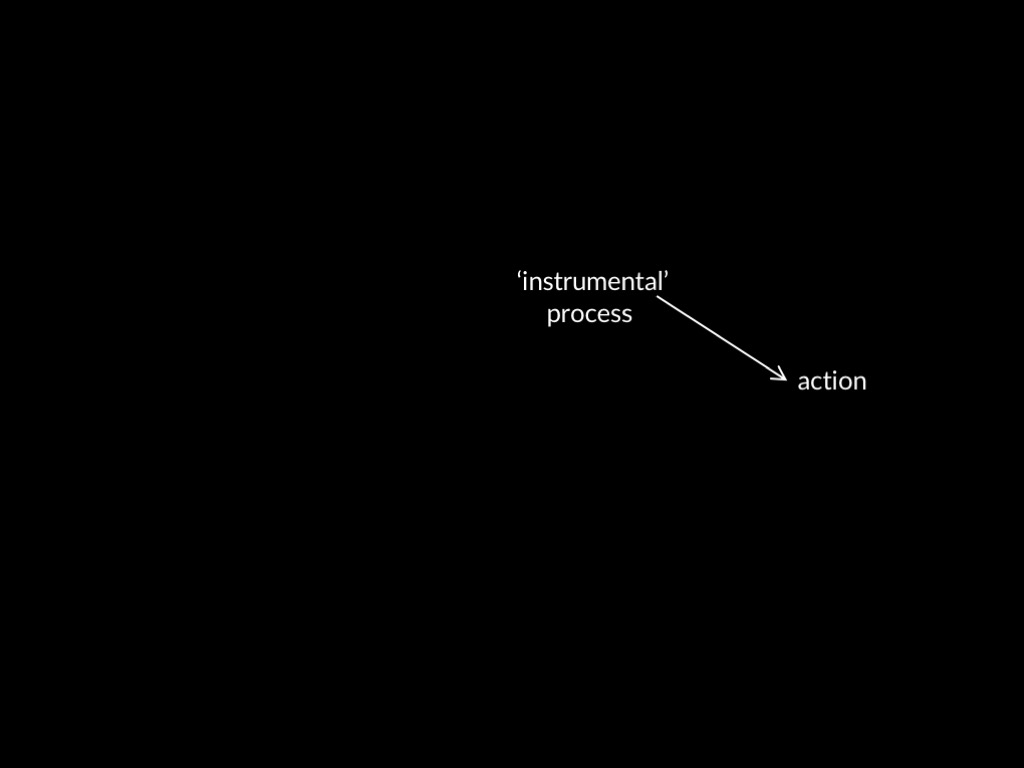

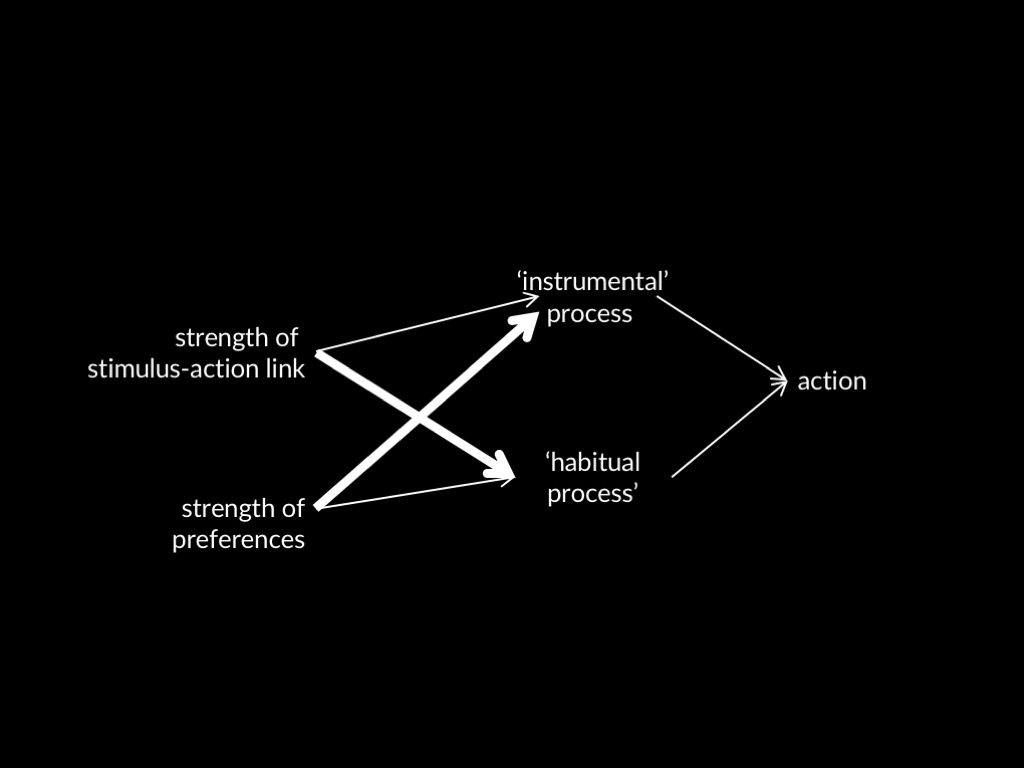

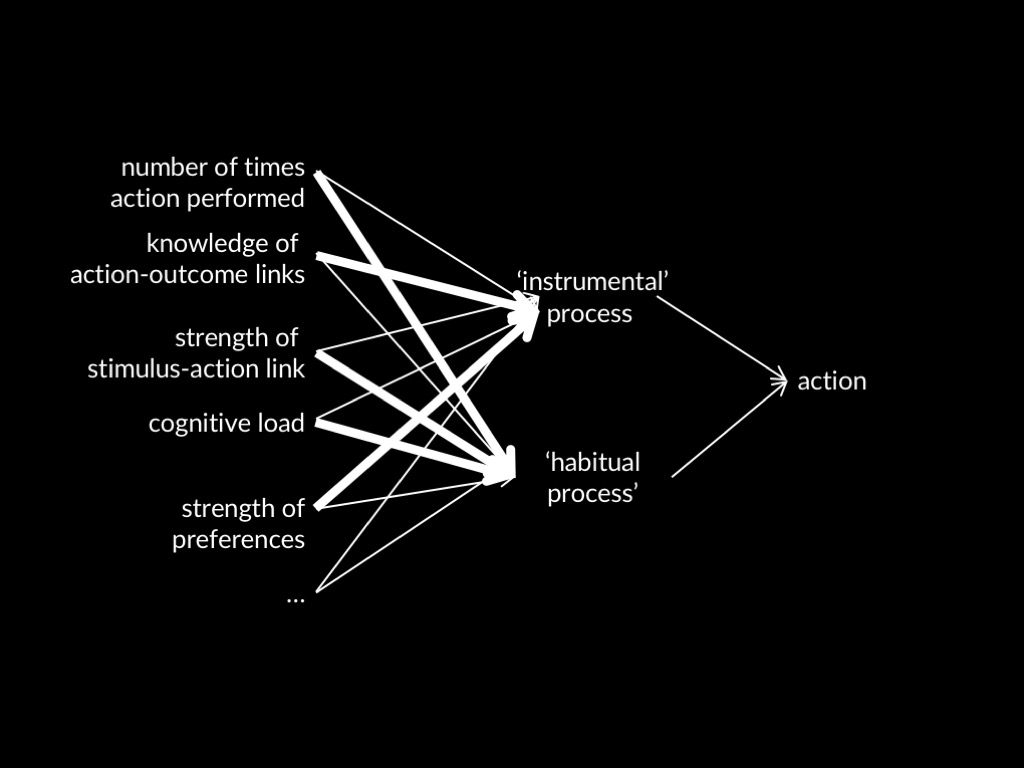

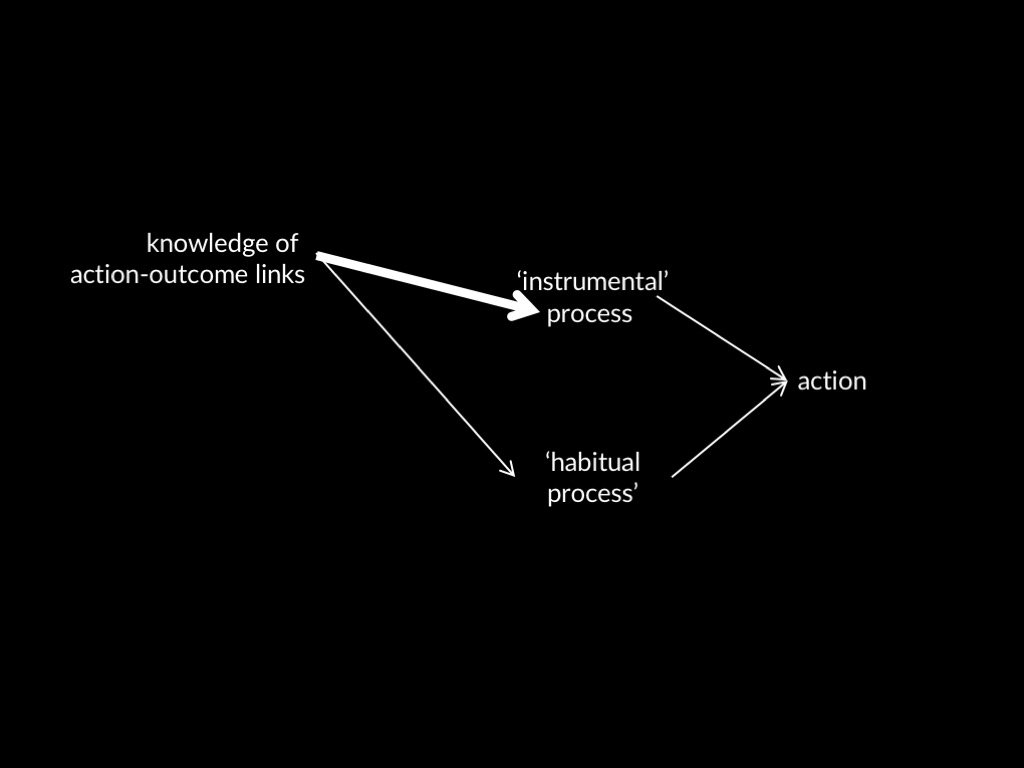

\section{Descision Theory Is Agnostic about Processes}

You might be tempted to interpret decision theory as a description

of how people reason. Is any such interpretation obligatory?

Observation of how decision theory is applied supports the conclusion

that decision theory is agnostic about processes.

You might have been interpreting decision theory as an account of how people figure out what to do ...

... but decision theory is agnostic about processes.

On explanation: ‘Many events and outcomes prompt us to ask: Why did that happen? [...] For example, cutthroat competition in business is the result of the rivals being trapped in a prisoners’ dilemma’

\citep[p.~36]{dixit:2014_games}.

Dixit et al, 2014 p. 36

Few would hold that game theory is providing an account of how businesses figure out what to do.

After all, few would hold that businesses (as opposed to the people who run them) figure things out.

The explanation does not require that any of the players are actually thinking along the lines a game theorist

would think. Nor even that the players are capable of thinking.

Games with the Prisoner’s Dilemma structure arise in:

bower birds (maraud/guard nests)

business organisations (product pricing)

countries (international environmental policy)

individual adult humans (suspects under arrest)

Dixit et al, 2014 chapter 10

There is clearly no claim that the same kinds of processes underpin the choices made

in each of these cases. Suppose, for the sake of illustration, that game theory can

explain otherwise unexpected patterns in performance in each of these cases.

What else follows about the proceses underlying the behaviours? Nothing.

Game theory provides a way to identify patterns in behaviours.

It does not attempt to explain the underlying causes of those patterns,

which may differ between entities.

If we look at game theory more generally, we find that game theoretic analysis has been

applied to ‘the formation and propagation of patterns in microbial populations’ \citep[e.g.][]{reichenbach:2007_mobility}.

1. Applications range from microbial populations to countries.

2. The explanations are of the same type in every case.

3. The underlying processes probably differ.

4. Therefore, game theory is agnostic about processes.

\begin{enumerate}

\item Applications of game theory range from interactions between microbial populations to interactions between countries.

\item The explanations are of the same type in every case.

\item The underlying processes probably differ.

\item Therefore, game theory is agnostic about processes.

\end{enumerate}

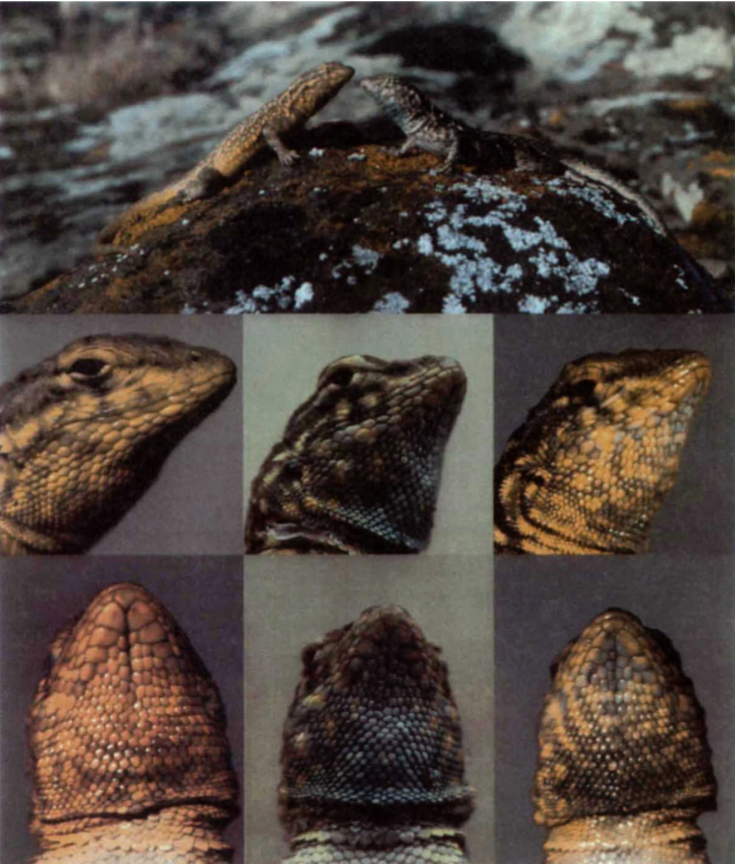

I couldn’t resist this one ... game theory (rock-paper-scissors specifically)

has been used to explain ‘evolutionary stable strategy model to a three-morph mating system in the side-blotched lizard’

\citep{sinervo:1996_rock}.

(The ones on the right resemble sexually receptive females morphologically; they are

‘sneakers’.)

Decision theory is agnostic about processes.

What’s the message? Decision theory is agnostic about processes.

Let’s have the argument one more time ...

Compare explanation of patterns of behaviour in:

male side-blotched lizard morphology

vs

children playing rock-paper-scissors.

In explaining lizard morphology, it would be strange to think that the behaviours are a

result of anything cognitive at all.

By contrast, in the case of humans, and perhaps other animals, there are supposed to be

cognitive factors involved.

But psychological sciences are not agnostic about processes ...

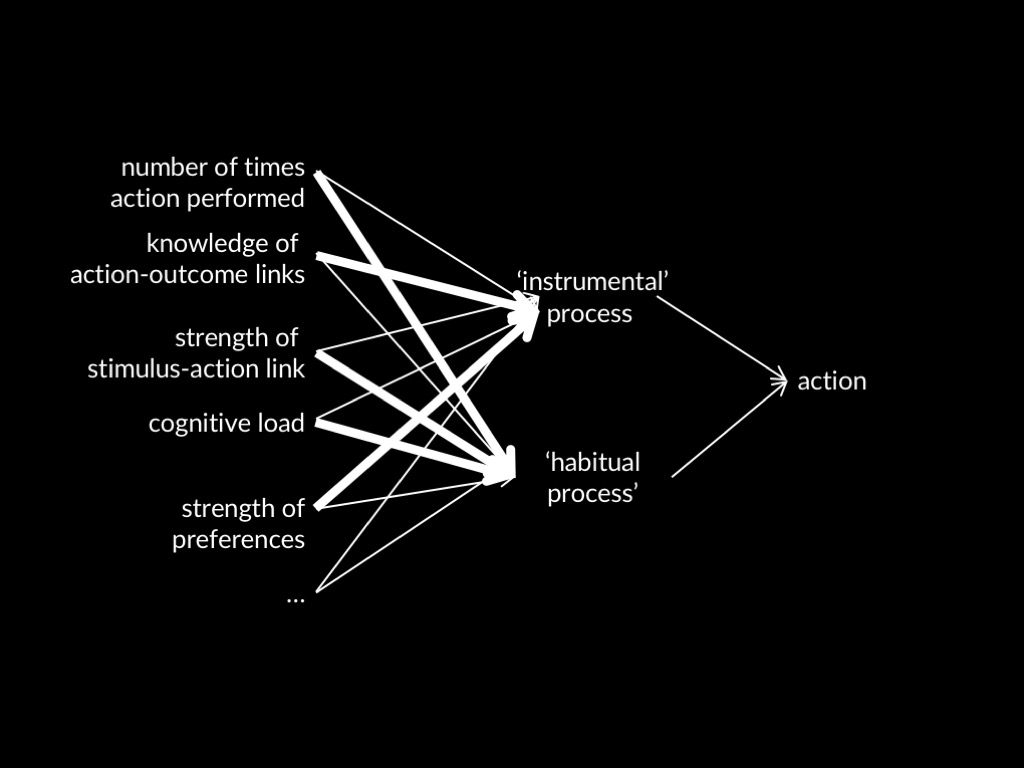

Processes: Habitual vs Instrumental

\section{Processes: Habitual vs Instrumental}

What kinds of processes in individual animals guide actions?

Research in animal learning enables us to distinguish habitual and instrumental processes

(see Dickinson, 1985).

What kinds of processes in individual animals guide actions?

What kinds of processes in

individual animals

guide actions?

habitual

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Agent is rewarded [/punished]

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened [/weakened] due to reward [/punishment]

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

Let’s check we all understand the key terms here.

Action may be a complex, coordinated goal-directed action, such as pressing a lever.

habitual vs habitual

‘A habitual action, state, or way of behaving is one that someone usually does or has, especially one that is considered to be typical or characteristic of them.’

Habitual

Thorndyke’s Law of Effect:

\emph{Thorndyke’s Law of Effect}:

‘The presentation of an effective [=rewarding] outcome following an action [...] reinforces

a connection between the stimuli present when the action is performed and the action itself

so that subsequent presentations of these stimuli elicit the [...] action as a response’

\citep[p.48]{Dickinson:1994sm}

Dickinson, 1994 p. 48

habitual

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Agent is rewarded [/punished]

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened [/weakened] due to reward [/punishment]

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

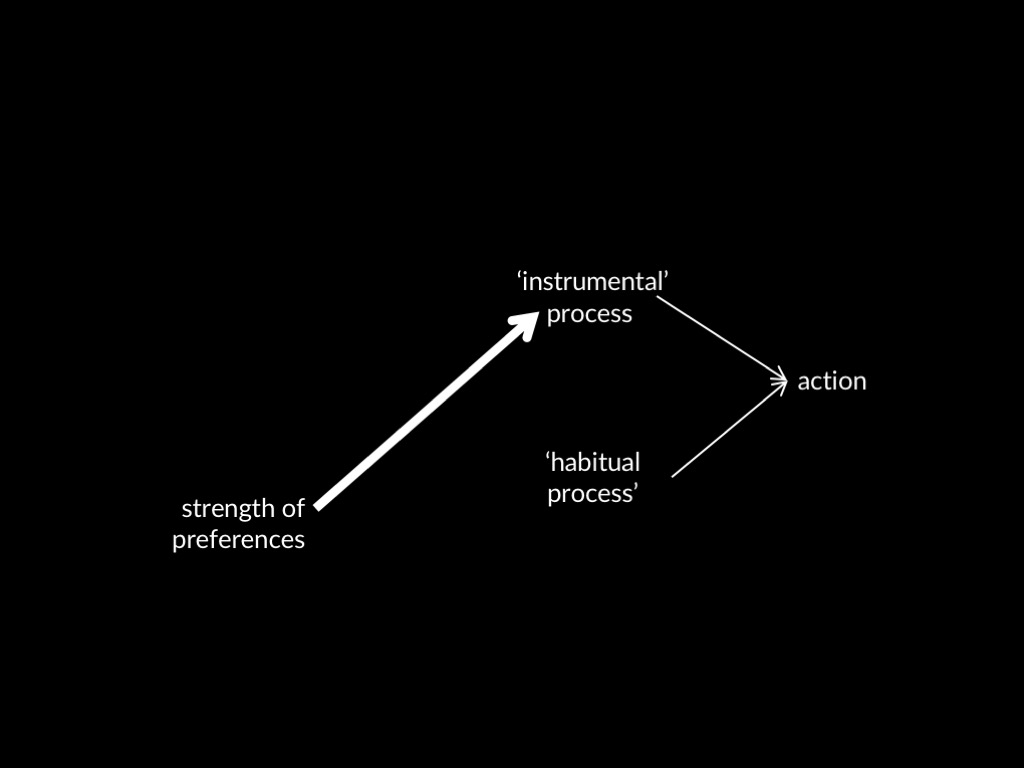

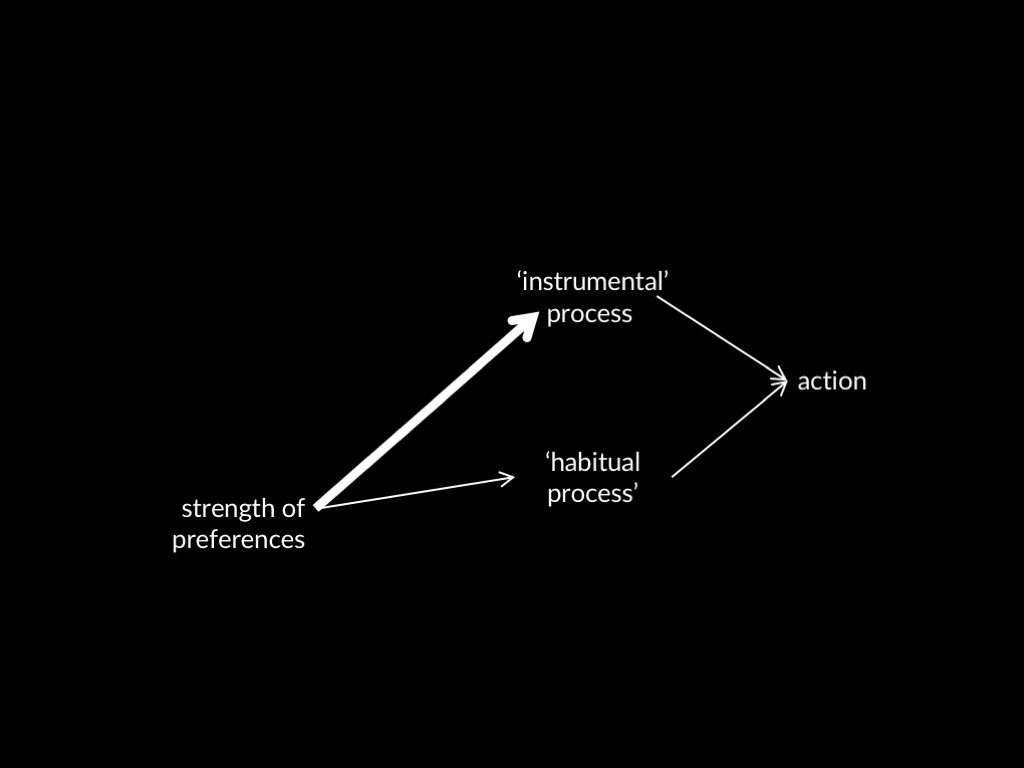

instrumental

Action leads to Outcome.

Action-Outcome Link is strengthened.

Agent has strong [/weak] positive [/negative] Preference for Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the strength of Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Preference.

\section{A Puzzle about Action}

A rat has been given food contingent on its pressing a level.

When it presses the lever, is its action habitual or instrumental?

(This part also explains devaluation.)

You see a rat and a lever.

The rat presses the lever occasionally.

Now you start rewarding the rat:

when it presses the lever it is rewarded with a particular kind of food.

As a consequence, the rat presses the lever more often.

Is this lever pressing habitual or instrumental aciton?

habitual

Stimulus is the layout of this room.

Rat (=Agent) is rewarded with food

Room-LeverPress (=Stimulus-Action) Link is strengthened due to reward

Thf LeverPress (=Action) will occur in this room (=Stimulus).

instrumental

Lever pressing (=Action) leads to food (=Outcome).

Thf LeverPress-Food (=Action-Outcome) Link is strong.

Rat (=Agent) has strong positive Preference for food.

Thf LeverPress (=Action) will occur.

Problem: different hypotheses, same prediction

What if we devalue the food?

Explain devaluation (poison, or satiation)

habitual

Stimulus is the layout of this room.

Rat (=Agent) is rewarded with food

Room-LeverPress (=Stimulus-Action) Link is strengthened due to reward

Thf LeverPress (=Action) will occur in this room (=Stimulus).

instrumental

Lever pressing (=Action) leads to food (=Outcome).

Thf LeverPress-Food (=Action-Outcome) Link is strong.

Rat (=Agent) has strong positive Preference for food.

Thf LeverPress (=Action) will occur.

Devaluation affects Preference, so changes what the instrumental hypothesis predicts.

Devaluation does not affect the Simulus-Action link.

(It’s the fact that food was preferred in the past that matters:

because of this, getting food was rewarding and so strengthened the

Simulus-Action link.)

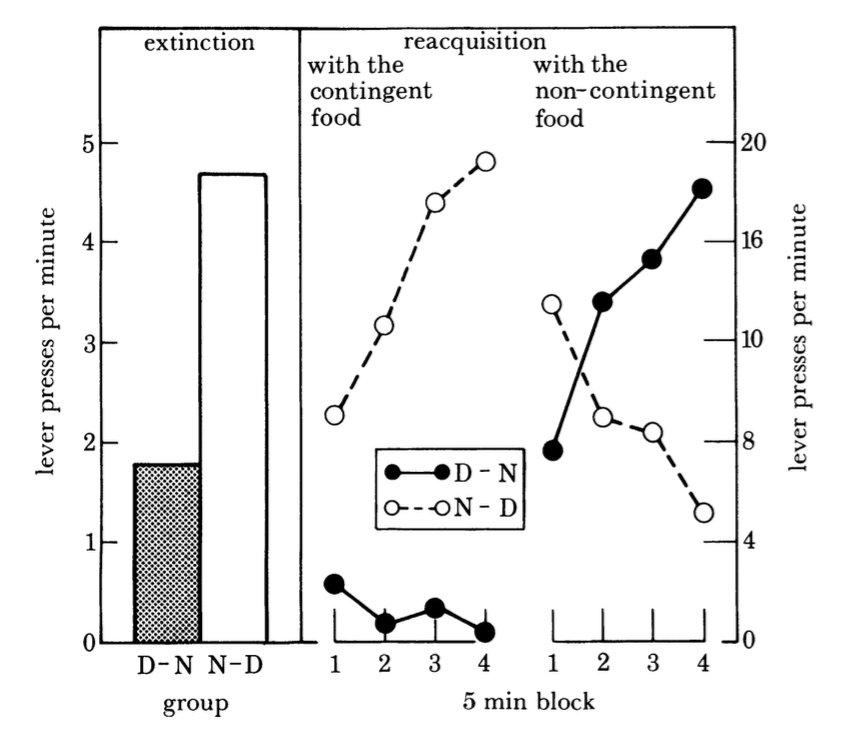

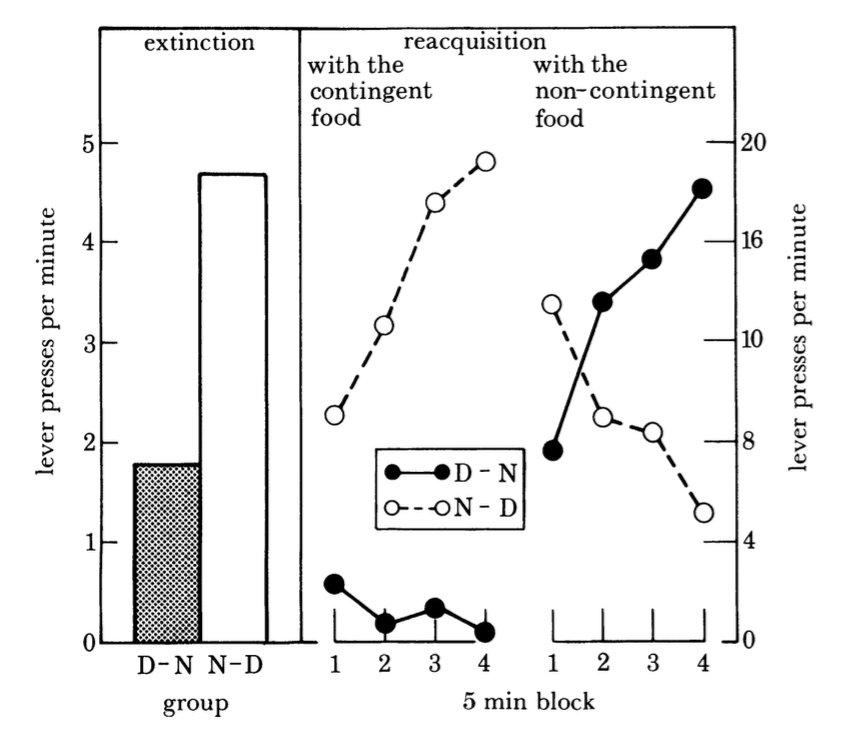

What if we devalue the food?

Instrumental : it will reduce lever pressing (to none)

Habitual : it will have no effect on lever pressing

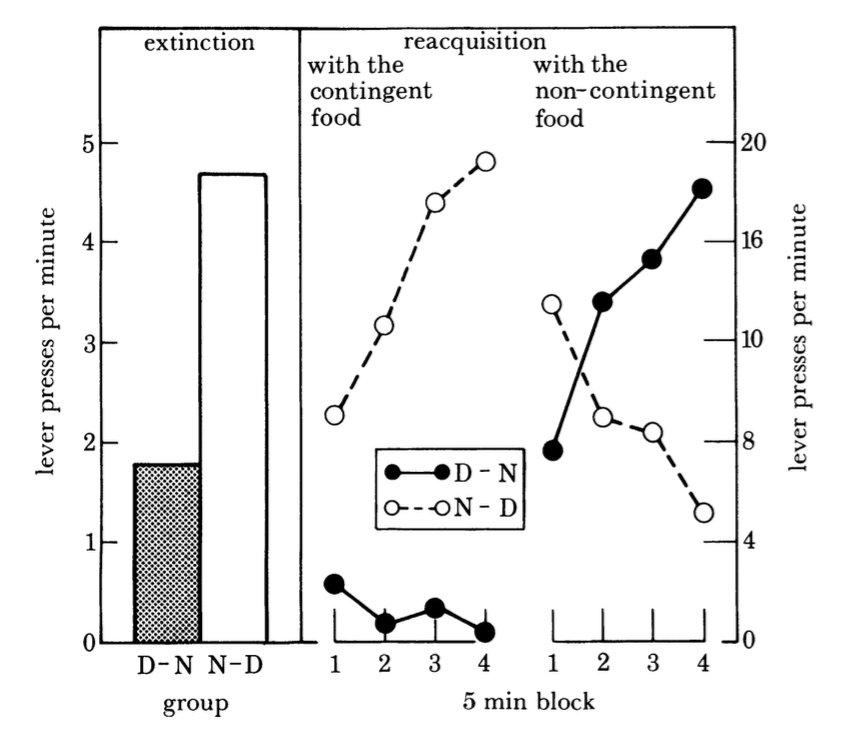

‘Mean lever-press rates during the extinction (left-handpanel) and reacquisitiontests(right-handpanel) followingthe devaluation of either the contingent (group D-N) or non-contingentfood (group N-D).’

Dickinson, 1985 figure 3

What if we devalue the food?

Instrumental : it will reduce lever pressing (to none)

Habitual : it will have no effect on lever pressing

(a) Rat’s behaviour is instrumental (explained by their Preferences).

(b) Hypotheses about processes underpinning decisions are scientifically testable.

‘the laboratory rat fits the teleological [instrumental] model; performance of this particular instrumental behaviour really does seem to be controlled byknowledge about the relation between the action and the goal’

\citep[p.~72]{Dickinson:1985qp}

Dickinson, 1985 p. 72

But there is a complication ...

‘we did not conclude that all such responding was of this form.

Indeed, we observed some residual

responding during the post-re-valuation test that appeared to be impervious to outcome devaluation

and therefore autonomous of the current incentive value,

and we speculated that this responding was

habitual

and established by a process akin to the stimulus-response (S-R)/reinforcement mechanism

embodied in Thorndike’s classic Law of Effect (Thorndike, 1911).

\citep[p.~179]{dickinson:2016_instrumental}

Dickinson, 2016 p. 179

‘Mean lever-press rates during the extinction (left-handpanel) and reacquisitiontests(right-handpanel) followingthe devaluation of either the contingent (group D-N) or non-contingentfood (group N-D).’

Dickinson, 1985 figure 3

The puzzle:

\begin{enumerate}

\item If the action is habitual, why is it modulated by devaulation?

\item If the action is instrumental, why does it still occur (albeit less frequently) after devaluation?

\end{enumerate}

puzzle

If the action is habitual,

why is it modulated by devaulation?

If the action is instrumental,

why does it still occur (albeit less frequently) after devaluation?

Solution is to stop thinking that actions can be just one or the other.

\emph{The instrumental/habitual distinction concerns proceses, not actions!}

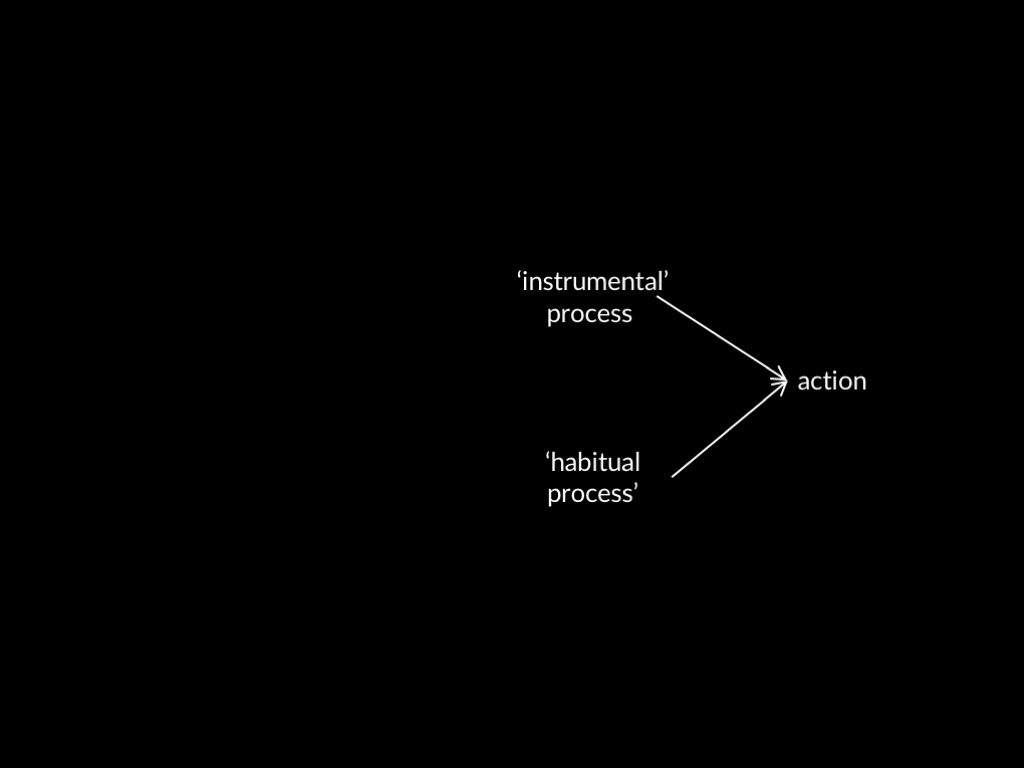

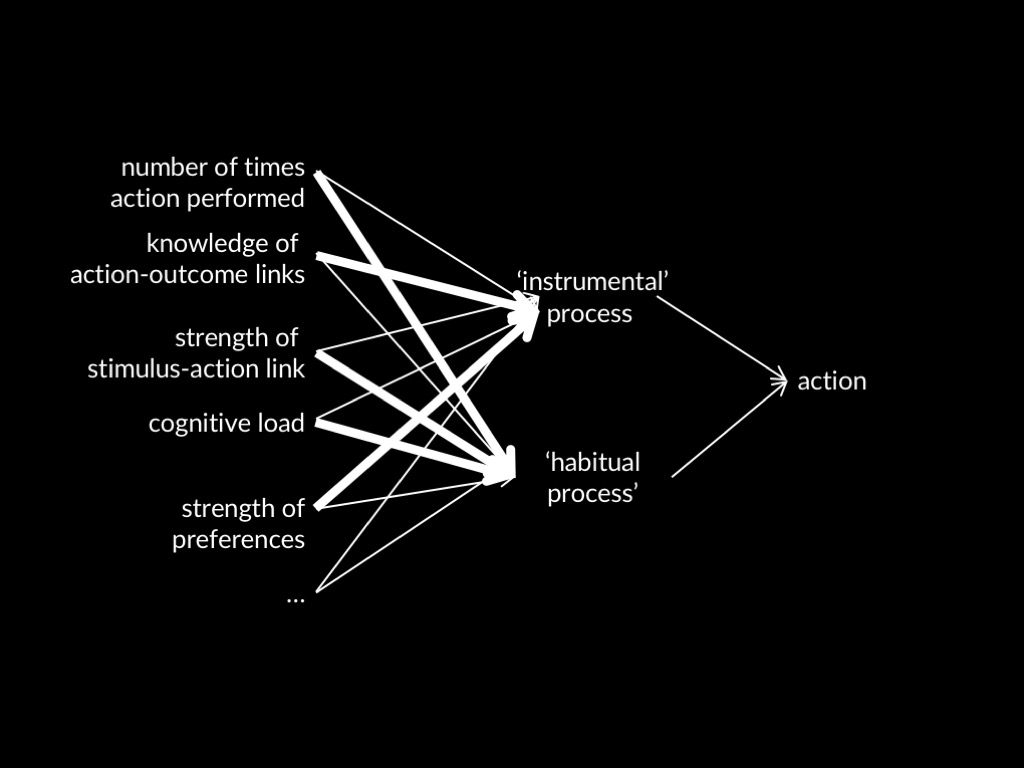

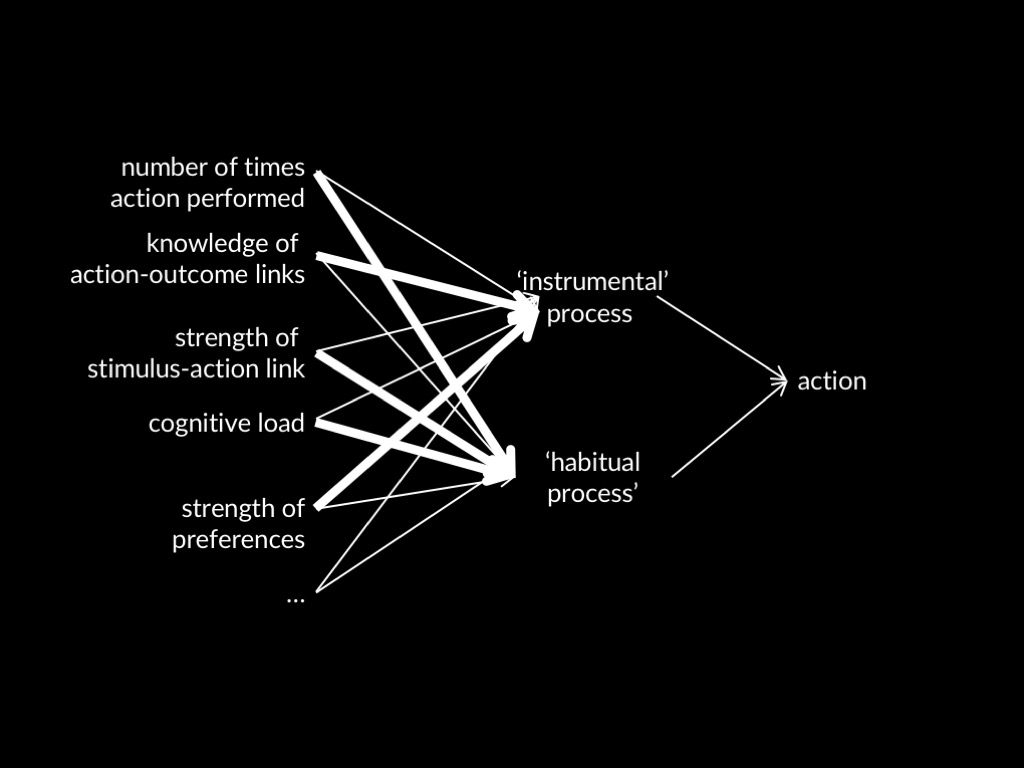

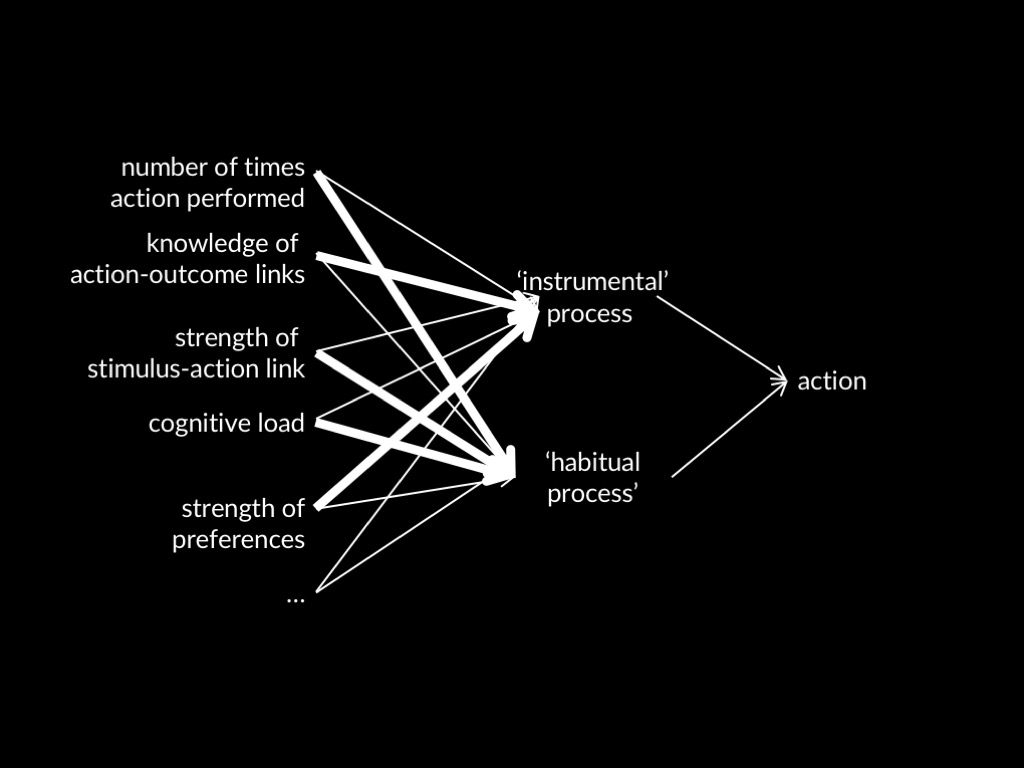

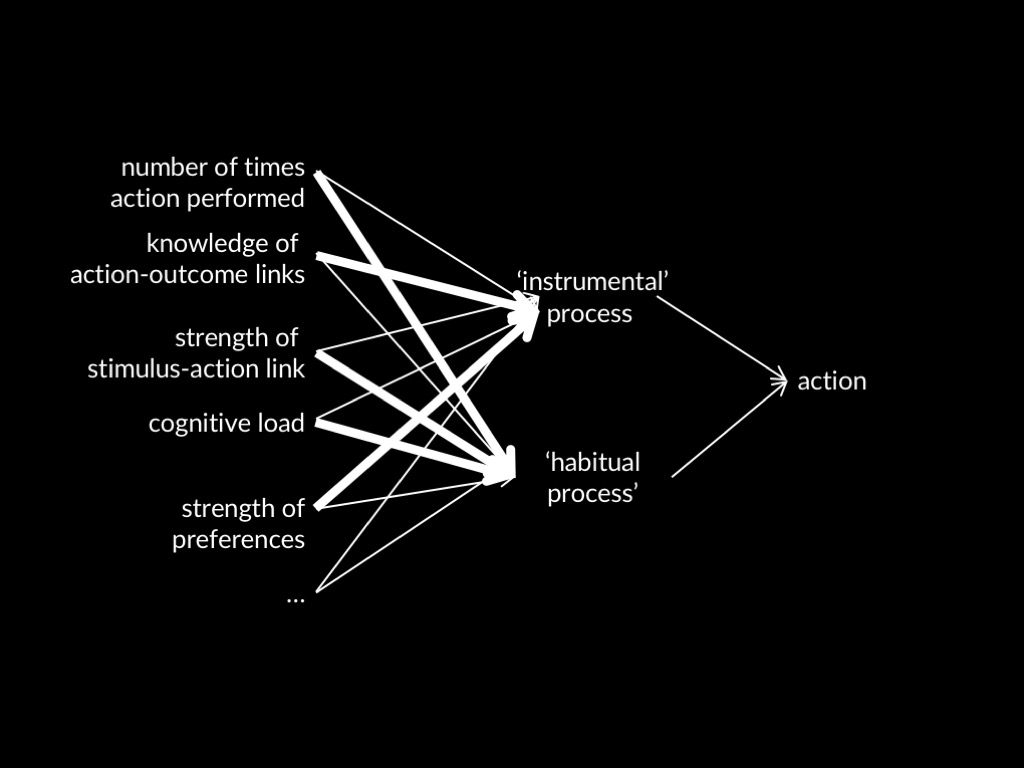

A Dual-Process Theory of Action

\section{A Dual-Process Theory of Action}

Actions are neither habitual or instrumental.

Actions are controlled by two or more distinct kinds of

process, one instrumental and the other habitual.

Dual-Process Theory of Action

some actions are ‘controlled by two dissociable processes: a goal-directed [instrumental] and an habitual process’

\citep{Dickinson:1985qp,dickinson:2016_instrumental}

Dickinson, 2016 p. 179

Something that can be interrupted

There are interventions which affect one process differently from the other.

These are technical terms

Earlier I asked,

You see a rat and a lever.

The rat presses the lever occasionally.

Now you start rewarding the rat:

when it presses the lever it is rewarded with a particular kind of food.

As a consequence, the rat presses the lever more often.

Is this lever pressing habitual or instrumental aciton?

Now we can say the question is confused.

Are the causes of this action habitual or instrumental? Both!

Neurophysiological Evidence

‘[instumental] and habitual control have been doubly dissociated in two brain regions.

In the PFC, lesions of the prelimbic and infralimbic areas disrupt goal-directed [instrumental] and habitual behavior, respectively ...

These dissociations suggest that different neural

circuits mediate the two forms of control’

Dickinson, 2016 p. 184

\citep[p~184]{dickinson:2016_instrumental}

\section{Stress}

When stressed,

your preferences matter less:

habits dominate (Schwabe & Wolf, 2010).

‘instrumental behavior itself involves two systems, the goal-directed and the habitual’

\citep[p.~12]{dickinson:2018_actions}

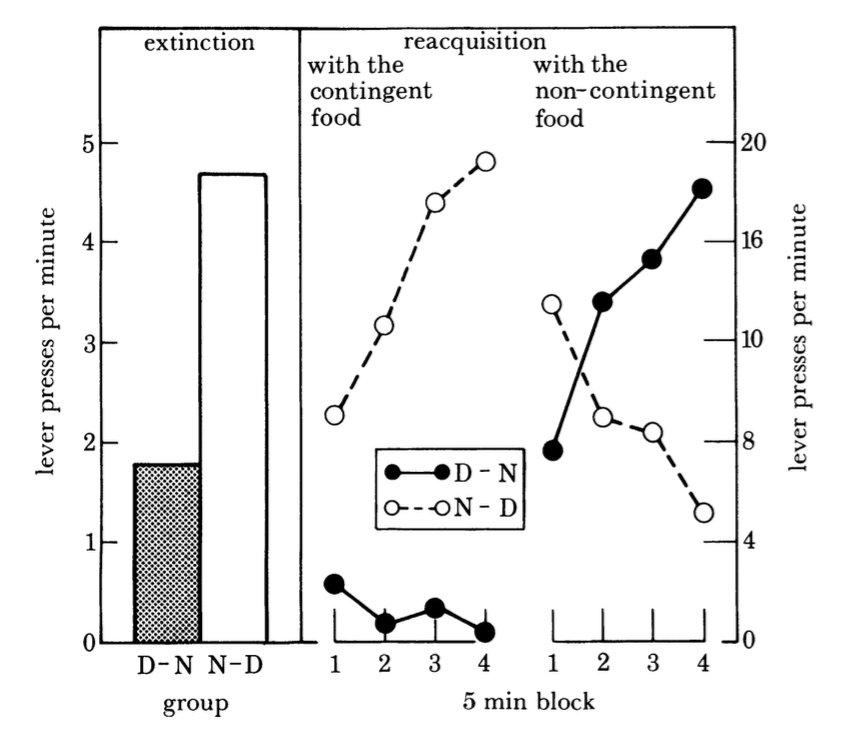

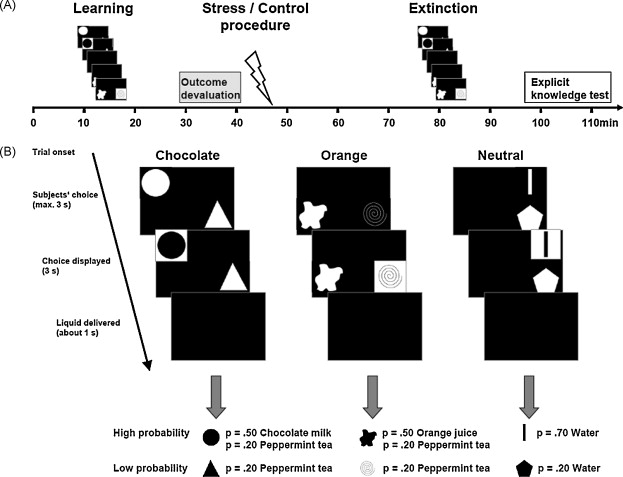

Illustration: stress (Schwabe & Wolf, 2010)

Schwabe and Wolf, 2010 figure 1

‘Figure 1. (A) Time line of the experiment. Participants were first trained in the instrumental task. After the selective outcome devaluation (satiation with oranges or chocolate pudding) but before the extinction test, subjects were exposed to stress (socially evaluated cold pressor test) or a control condition. (B) The instrumental task (reproduced with permission from the Society for Neuroscience). Participants completed three trial types (chocolate, orange, and neutral). In each trial type, there was one action that led with a high probability to a food outcome and one action that led with a low probability to a food outcome. Depending on the trial type, the high probability action yielded chocolate milk or orange juice with a probability of p = 0.5, a common outcome (peppermint tea) with a probability of p = 0.2, or nothing. The low probability action led to the common liquid with a probability of p = 0.2. After an action was chosen, the referring symbol was highlighted for 3 s before the food was delivered. During the extinction test, chocolate milk and orange juice were no longer presented.’

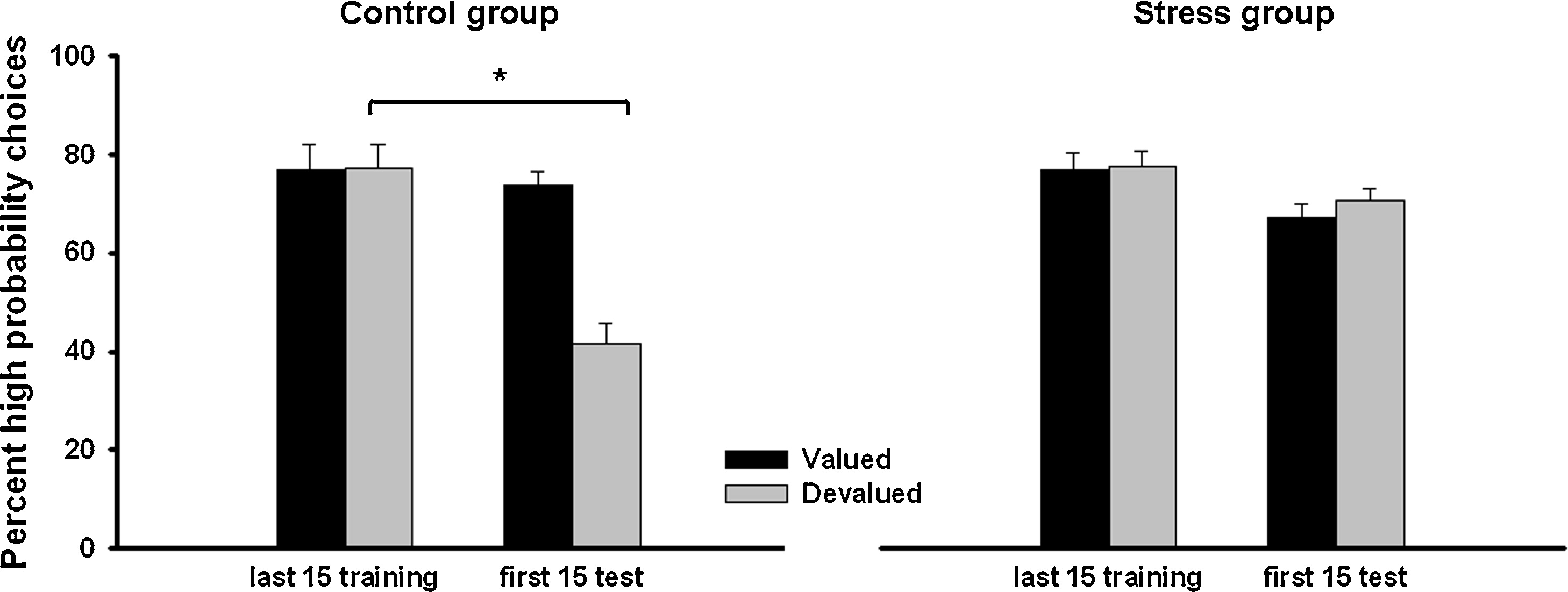

Schwabe and Wolf, 2010 figure 6

‘Figure 6. Percent high probability actions of controls and stressed participants in the last 15-trial block of training and the first 15-trial block of extinction testing. After selective outcome devaluation, controls showed a decrease in the choice of the high probability action associated with the food eaten to satiety (* p < .01) whereas the choice behavior of stressed participants was insensitive to the changes in outcome value. Data represent M ± SEM.’

When stressed,

your preferences matter less:

habits dominate.

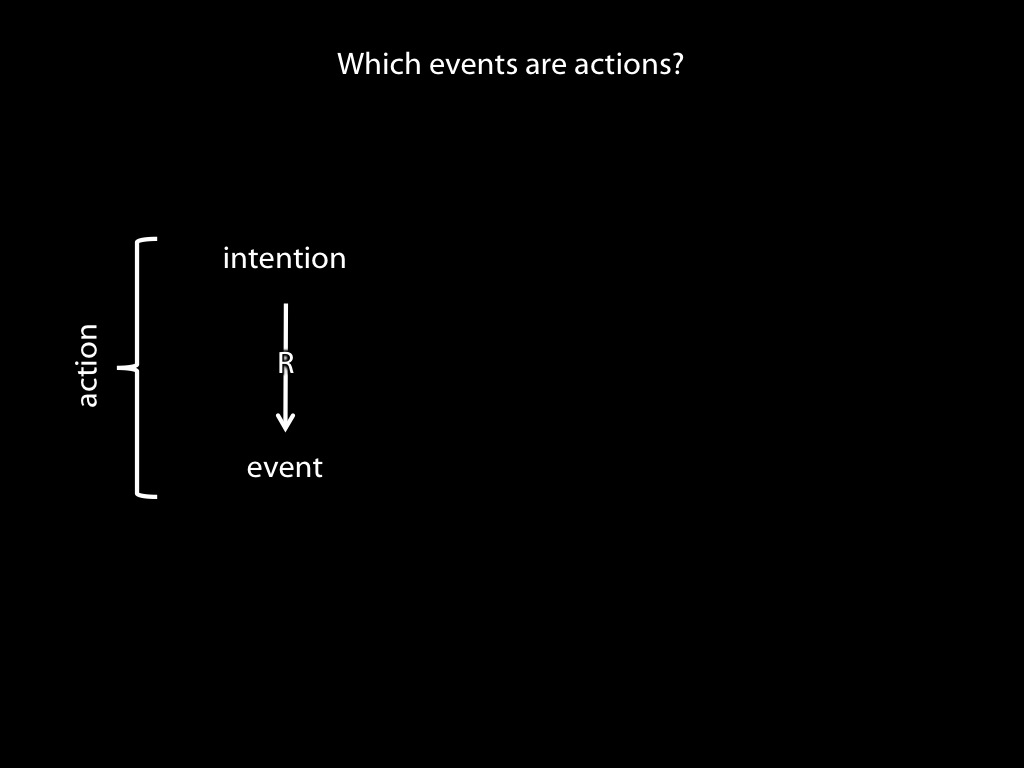

Q1

Donald Davidson asks, ‘What is the mark that distinguishes ... actions?’ Are scientific discoveries relevant to answering this question?

Q2

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Q3

How are non-accidental matches between intentions and motor representations possible?

Back to these questions ... is Dickinson relevant?

We’re confident that the lever pressing is an action

independently of whether it was caused by instrumental, habitual

or some combination of these.

Which events are actions?

In philosophy, answering this question would typically answered by appeal to intention

or practical reasoning.

Such views tend to be neutral on how

the attitudes and processes ultimately connect to bodily movements;

that is considered to be merely an implementation detail ...

They are neutral in this sense: the views do not depend in any way on facts about that

distinguish one kind of body from another, or on facts about how the body’s movements

are ultimately controlled ...

If events can be actions despite being dominated by habitual processes,

why are several philosophers confident that all actions are intentional?

‘once we accept that there are complex and subtle non-intentional processes, such as those mediating

basic goal-approach and the adjustment to changes in motivational state, that can mimic true

intentional control in many situations, we can understand why the propensity to perceive actions as

intentional may have developed. Given that

either there is nothing in the stimulus input per se to

distinguish intentional from non-intentional behaviour

or that

such a discrimination yields little of

consequence in most situations,

it may well pay the perceiver to treat both classes of behaviour as

intentional in predicting the subsequent course of events’

\citep[p.~102]{heyes:1990_intentionality}.

Heyes & Dickinson, 1990 p. 102

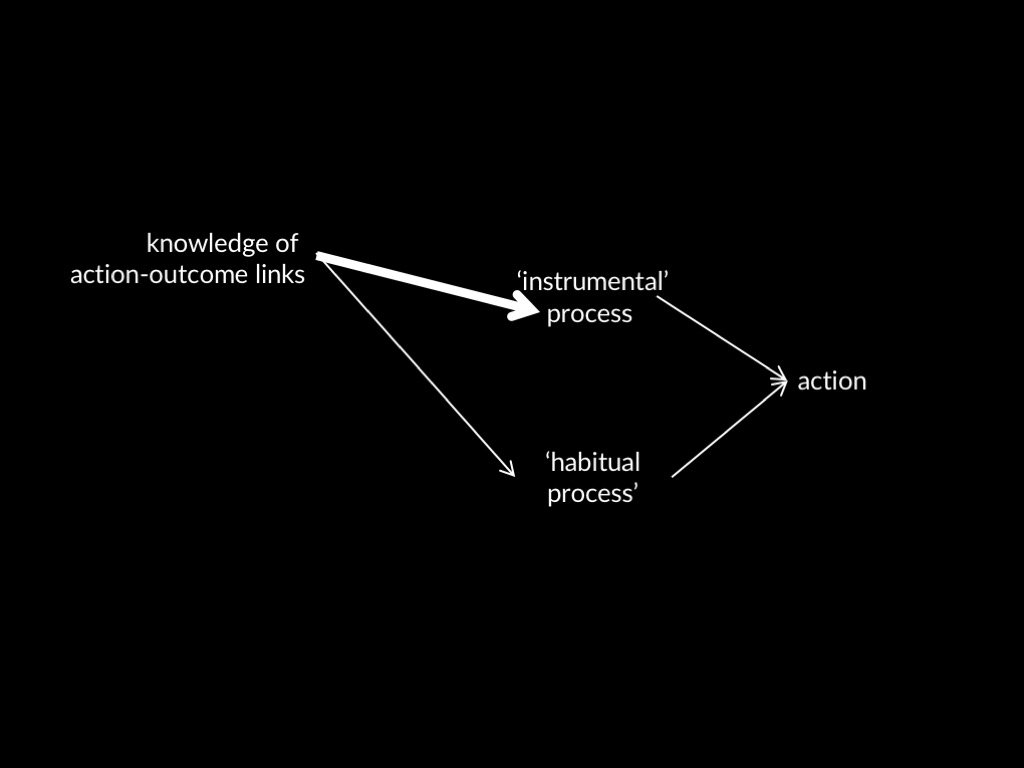

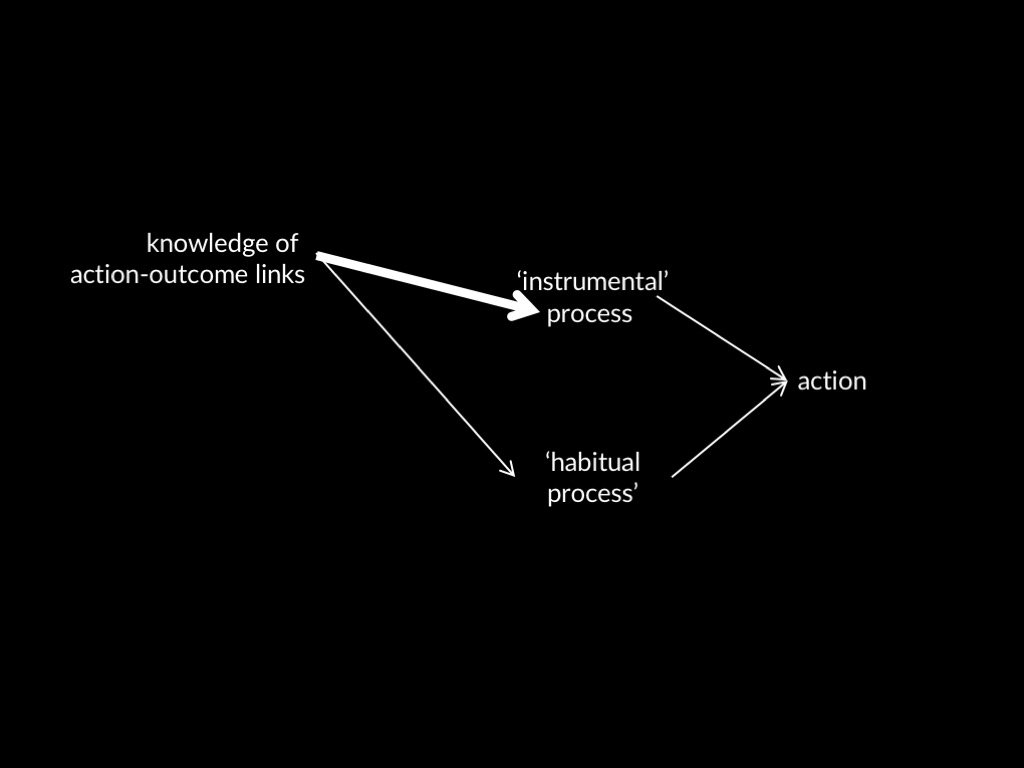

\section{Is Decision Theory Really Agnostic about Processes?}

The range of applications of decision theory

indicates that it must be agnostic about processes.

But Dickinson’s instrumental process is characterised by appeal to Decision Theory.

How can the apparent tension between these facts be resolved?

tension

ok, so what is this tension?

The range of applications of Decision Theory shows it is agnostic about processes.

Dickinson’s instrumental process is characterised by appeal to Decision Theory.

So why does decision theory play a role in characterising

instrumental processes?

habitual

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Agent is rewarded [/punished]

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened [/weakened] due to reward [/punishment]

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

instrumental

Action leads to Outcome.

Action-Outcome Link is strengthened.

Agent has strong [/weak] positive [/negative] Preference for Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the strength of Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Preference.

This is like an expectation (or a belief)

How are these combined?

In such a way as to maximise expected utility!

The range of applications of Decision Theory shows it is agnostic about processes.

Dickinson’s instrumental process is characterised by appeal to Decision Theory.

Before I resolve these tensions, I wanted to consider

decision theory vs game theory. Done that now.

So how can we resolve the tensions?

I think the key is to step back and think of Game theory as a model

Construals of Decision Theory

\section{Construals of Decision Theory}

Decision Theory specifies a model of action.

Models can be construed in several different ways.

Decision Theory says nothing about how the model should be construed.

My proposal:

\begin{quote}

Decision Theory (like Game Theory) specifies a model of action.

Models can be construed in several different ways.

Decision Theory says nothing about how the model should be construed.

\end{quote}

Alternatives exist. For instance, \citet{binmore:1994_playing} claims the axioms

of game theory are tautologies; on his story, the games are the models.

model vs construal

Source: Godfrey-Smith

e.g. model of a house

Model of a house.

Initially it’s aspirational [construal 1].

They you win the lottery.

Same model can be construed as a plan [construal 2].

Later, when the house is built, you use it as a map of the house [construal 3].

Then you realise that people are quite similar

and that what you thought was a unique design is something

that lots of other people would also want,

so you use the model to predict what others will want [construal 4].

another contrast:

model vs theory

‘Theories, as they are usually understood by philosophers, make claims about the

world [...]

Models, in my sense, do not themselves say anything about the

world.

Models are structures that can be used by scientists to say various

different things about the world,

by means of commentaries that accompany

models but are distinct from them’

\citep[p.~4]{godfrey-smith:2005_folk}.

Godfrey-Smith, 2005 p. 4

‘Two scientists can use the same model to help with the same target system while having quite different views of how the model might be representing the target system. I will describe this situation by saying that the two scientists have different construals of the model’

\citep[p.~4]{godfrey-smith:2005_folk}

‘one scientist might [construe] some model simply as an input-output device, as a

predictive tool.

Another might [construe] the same model as a faithful map of the

inner workings of the target system’

\citep[p.~4]{godfrey-smith:2005_folk}

Godfrey-Smith, 2005 p. 4

‘Basic facility with the folk-psychological model does not require using a

particular construal of it. Many construals are possible.

And it is also possible to have facility with the model, and have a sense of which target systems are appropriate for it, while not having much of a construal at all’

\citep[p.~5]{godfrey-smith:2005_folk}.

Godfrey-Smith, 2005 p. 5

Decision Theory (like Game Theory) specifies a model.

Models can be construed in several different ways.

Decision Theory says nothing about how the model should be construed.

What construals of Decision Theory might be useful?

- As a device for identifying behavioural patterns (‘revealed preference theory’)

- As a reconstruction of everyday reasoning, by reflective human adults, about what to do

- As a normative ideal

- As a model of how folk model minds and actions (a meta-model)

- As a computational description of a psychological processs

Decision Theory (like Game Theory) specifies a model.

Models can be construed in several different ways.

Decision Theory says nothing about how the model should be construed.

If we look at game theory more generally, we find that game theoretic analysis has been

applied to ‘the formation and propagation of patterns in microbial populations’ \citep[e.g.][]{reichenbach:2007_mobility}.

1. Applications range from microbial populations to countries.

2. The explanations are of the same type in every case.

3. The underlying processes probably differ.

4. Therefore, game theory is agnostic about processes.

The construals are different ... so the explanations differ significantly.

Decision Theory (like Game Theory) specifies a model.

Models can be construed in several different ways.

Decision Theory says nothing about how the model should be construed.

tension

ok, so did we resolve the tensions?

The range of applications of Decision Theory shows it is agnostic about processes.

Dickinson’s instrumental process is characterised by appeal to Decision Theory.

conclusion

In conclusion, ...

We need a dual-process theory of (goal-selection for) action.

Decision Theory (like Game Theory) specifies a model.

Models can be construed in several different ways.

Decision Theory says nothing about how the model should be construed.

Decision Theory provides a model that characterises the instrumental

goal-selection process

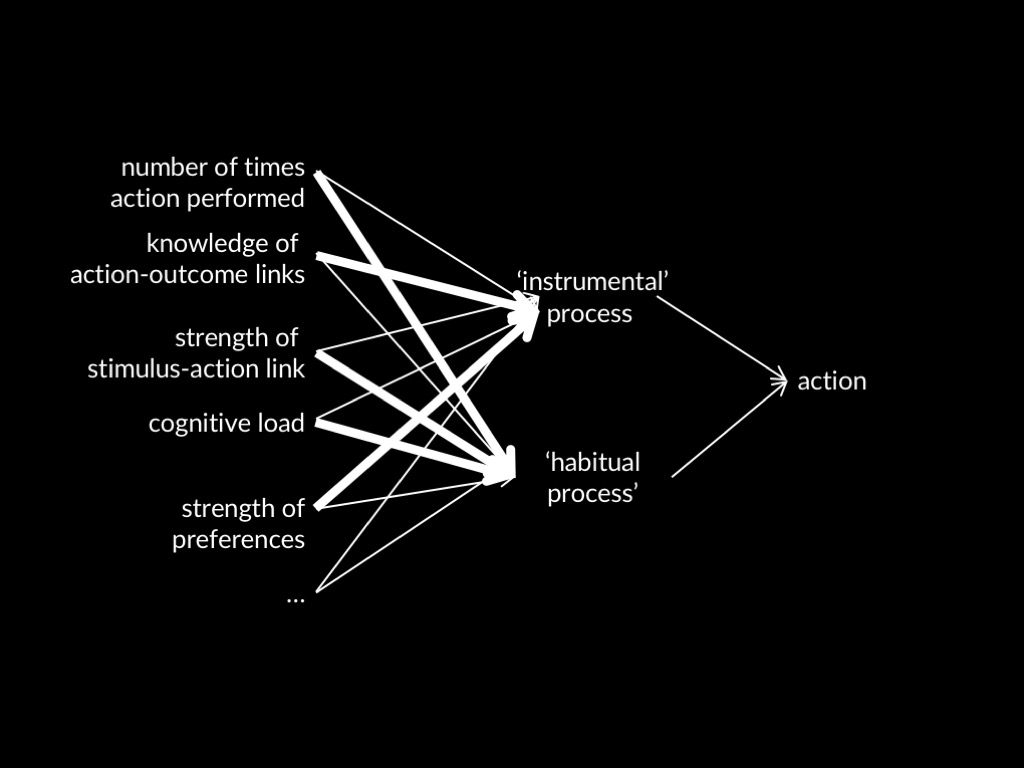

\section{Training Effects}

Whether you learn about the effects of an action

can influence

whether that action becomes dominated by instrumental or habitual processes (Klossek et al, 2011)).

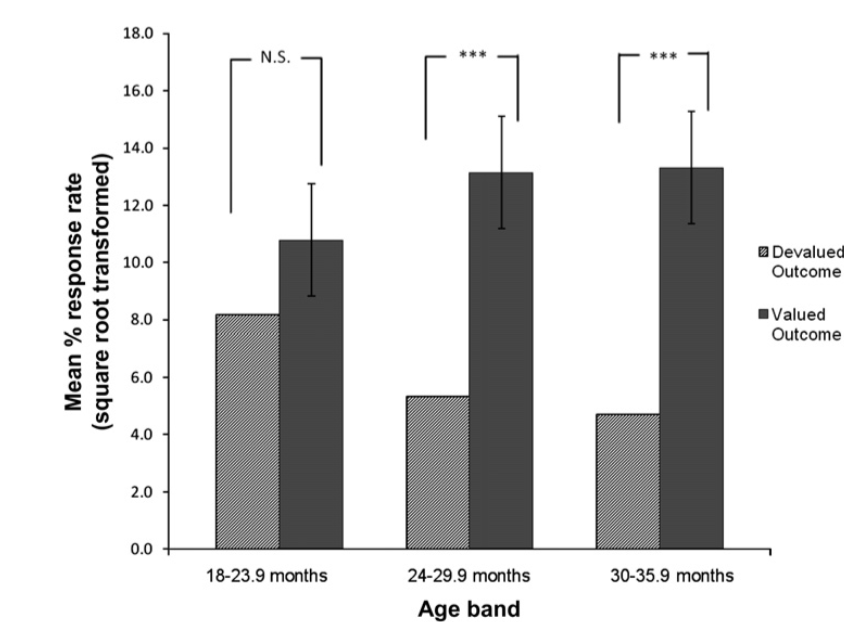

Klossek & Dickinson, 2012 figure 1a

This is from a different study than the one I will emphasise:

in this study they only demonstrate instrumental behaviour in young children.

Klossek & Dickinson, 2012 figure 2

Even young children can perform instrumental actions, but perhaps not very young children.

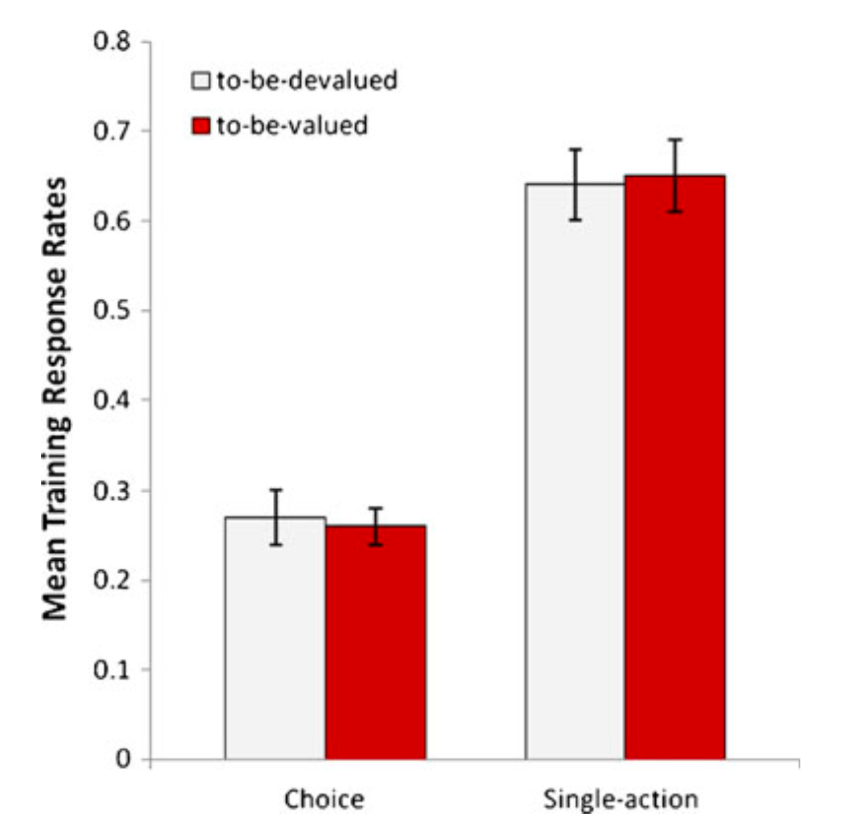

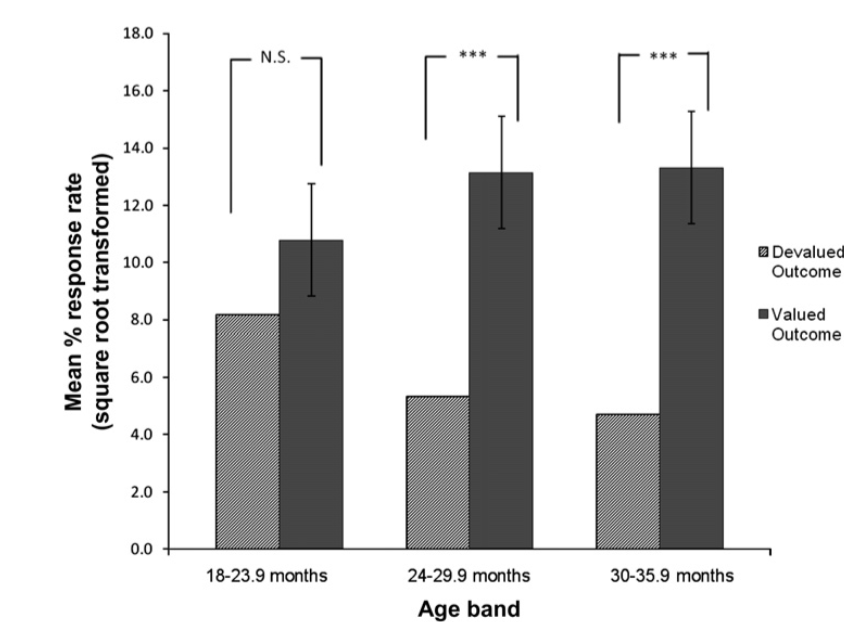

Training Effects (Klossek, Yu & Dickinson, 2011)

Source: \citep[p.~180]{dickinson:2016_instrumental}

Which is about Klossek, U. M. H., Yu, S., & Dickinson, A. (2011). Choice and goal-directed behavior in preschool children. Learning and Behavior, 39, 350-357.

Subjects: 3-4 year olds

Training:

Choice Group : perform Action1 to see Clip1 or Action2 to see Clip2

Single-Action Group : only one action is available at once

(Frequency of Action1 and Action2 is matched across groups!)

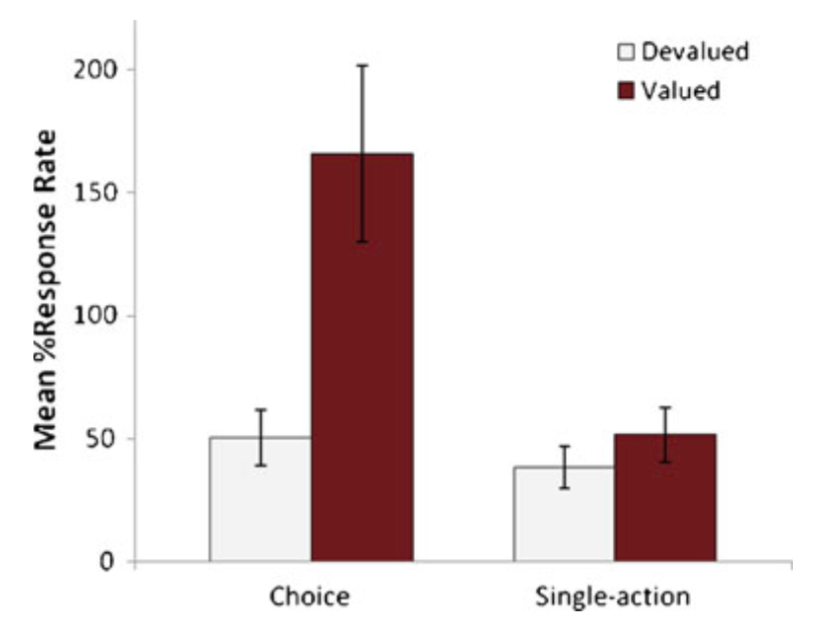

Devalue Clip1 (expose to satiety)

Test: both actions available. What do Ss select?

Results:

Choice group selects Action2

Single-Action Group selects Action1 and Action2 equally

As predicted if Instrumental

As predicted if Habitual

‘We argued that the variation in the development of behavioral autonomy arose from the different contingency experienced of the two groups. Once responding at a high and constant rate in the single-action condition after extended training, agents no longer experience the full causal contingency, speci cally episodes in which they do not respond and do not receive the outcome. As a result, the action-outcome causal representation necessary for goal-directed action is not maintained.’

\citep[p.~181]{dickinson:2016_instrumental}

Klossek et al, 2011 figure 1

‘Mean response rates per second during training for the choice and single-action groups. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means’

Klossek et al, 2011 figure 2

‘Mean percentage response rates for the choice and single- action groups during the postdevaluation extinction test. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means’

Whether you learn about the effects of an action

can influence

whether that action becomes dominated by instrumental or habitual processes.