Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

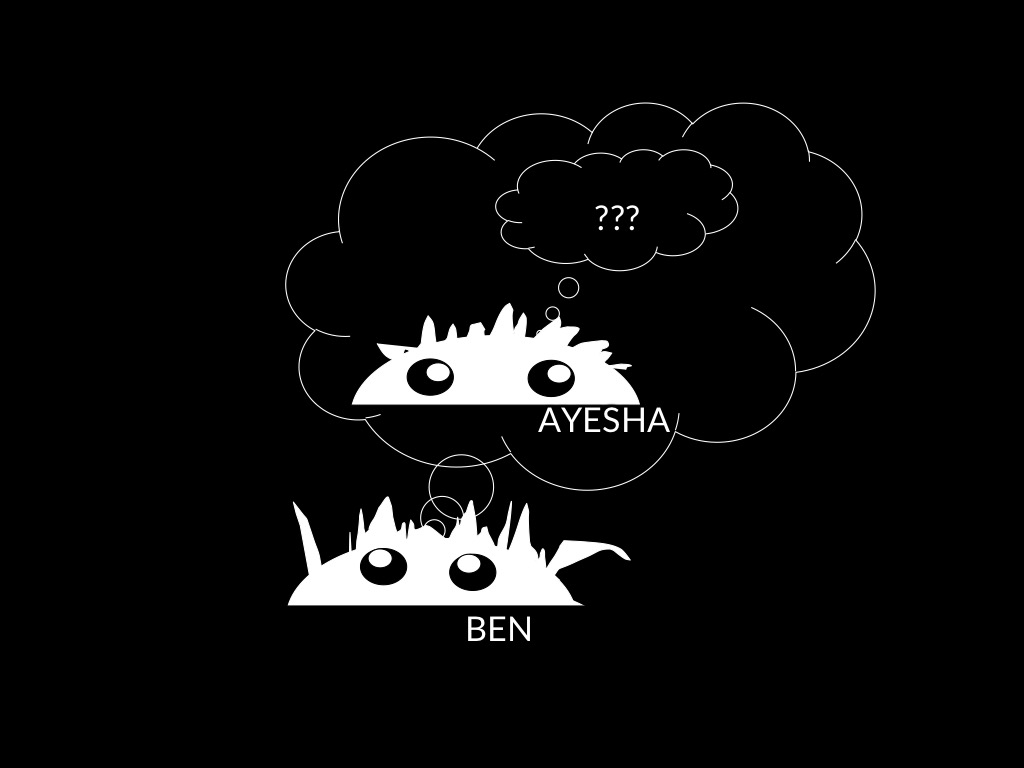

My topic is mindreading, the process of identifying mental states and purposive actions as

the mental states and purposive actions of a particular subject.

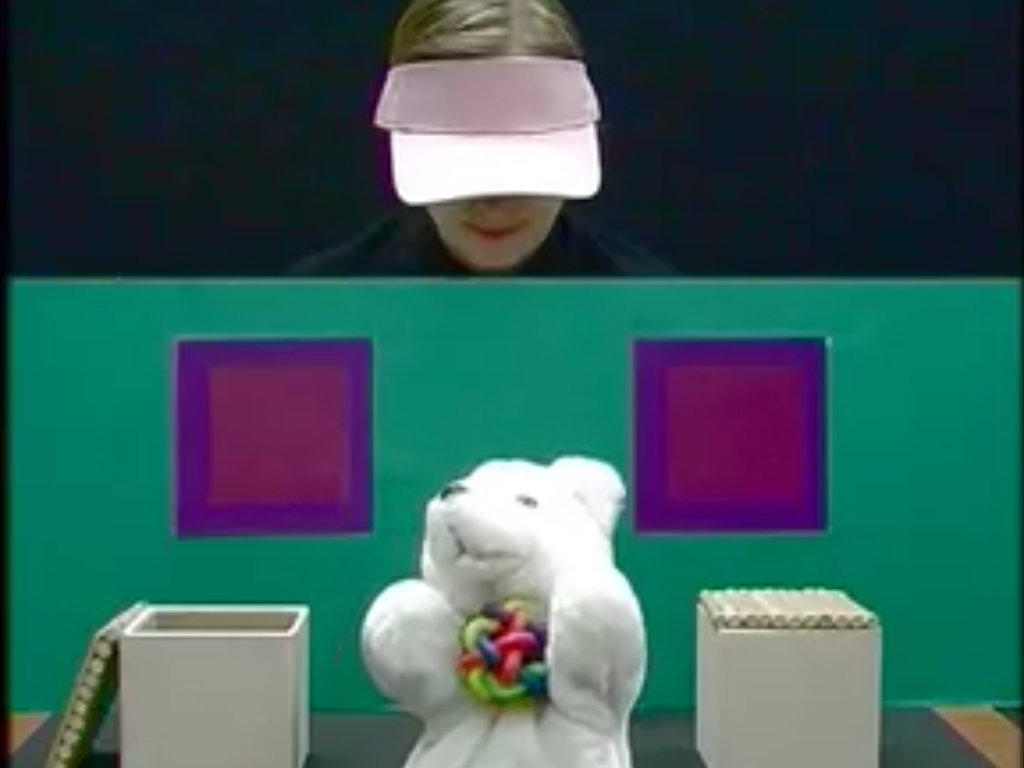

Let me start with a canonical illustration of mindreading in action.

Which box will Maxi look in?

Maxi wants his chocolate.

Maxi believes his chocolate is in the blue box.

Maxi’s chocolate is in the red box.

Maxi will look in the blue box.

Maxi will look in the red box.

So where the nonmindreader uses facts to generate predictions about actions, the

mindreading attributes beliefs.

In many cases, you will get the same predictions whether you are mindreading

or just using facts. But in cases like this, where there are false belief,

the predictions can come apart.

\textbf{This means that we can detect mindreading by measuring action predictions.}

In what follows I’m going to focus on belief.

The existence of mindreading processes for tracking beliefs raises many questions:

\begin{enumerate}

\item Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes but not always automatic? (or automatic to varying

degrees)

\item How and why is automatic belief-tracking limited in ways that nonautomatic belief-tracking is not?

\item How and why are inhibition, attention and working memory involved in belief-tracking?

\item Why is there an age at which children pass some false belief tasks but systematically fail

others?

\item What feature or features distinguish the tasks these children fail from those they

pass?

\end{enumerate}

I think there is more than one kind of mindreading process which tracks beliefs.

That’s why my title is ...

07: Three Questions about Mindreading

\def \ititle {07: Three Questions about Mindreading}

\begin{center}

{\Large

\textbf{\ititle}

}

\iemail %

\end{center}

\section{Some Evidence}

Many animals including scrub jays (Clayton, Dally and Emery 2007), ravens (Bugnyar, Reber and Buckner

2016), goats (Kaminski, Call and Tomasello 2006), dogs (Kaminski et al. 2009), ringtailed lemurs

(Sandel, MacLean and Hare 2011), monkeys (Burkart and Heschl 2007; Hattori, Kuroshima and Fujita 2009)

and chimpanzees (Melis, Call and Tomasello 2006; Karg et al. 2015) reliably vary their actions in ways

that are appropriate given facts about another’s mental states.

Many animals including scrub jays \citep{Clayton:2007fh},

ravens \citep{bugnyar:2016_ravens},

goats \citep{kaminski:2006_goats},

dogs \citep{kaminski:2009_domestic},

ringtailed lemurs \citep{sandel:2011_evidence},

monkeys \citep{burkart:2007_understanding, hattori:2009_tufted}

and chimpanzees \citep{melis:2006_chimpanzees,karg:2015_chimpanzees} reliably vary their actions in ways that are appropriate given facts about another’s mental states.

What could underpin such abilities to track others’ mental states?

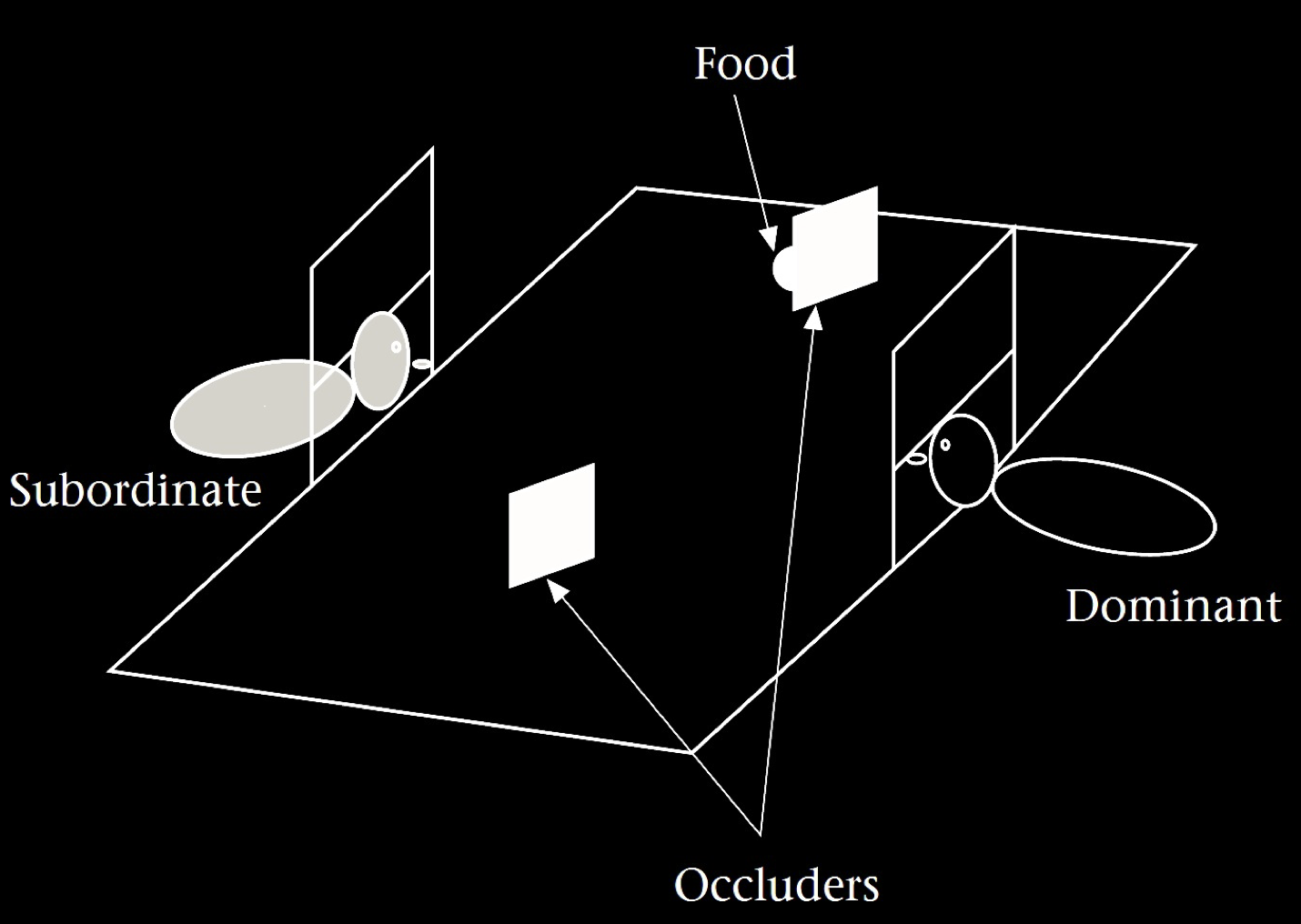

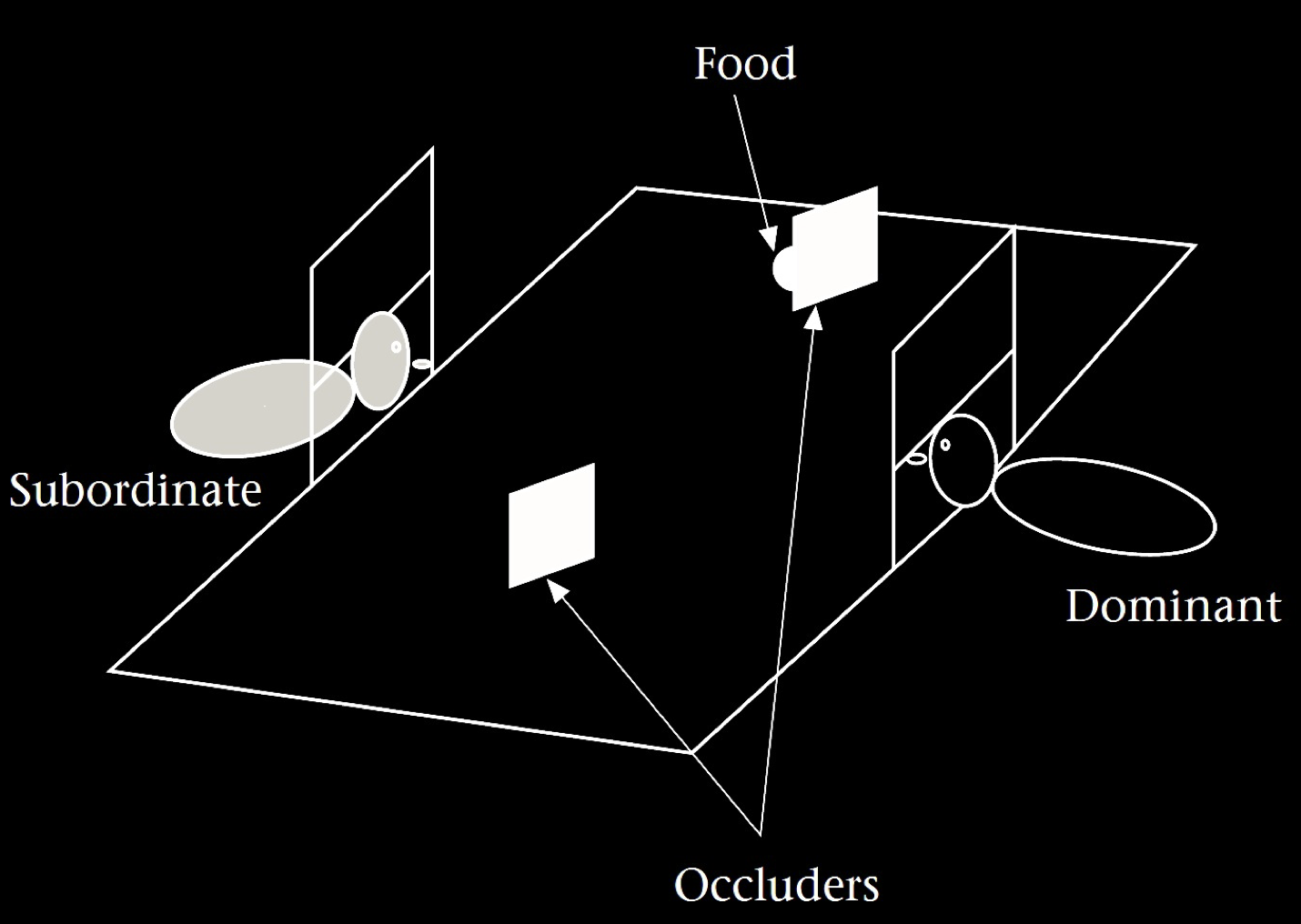

Hare et al (2001, figure 1)

In this experiment by Brian Hare and colleagues, a subordinate chimpanzee makes predictions about a

dominant chimpanzee’s ability to retrieve food. They found that the subordinate’s predictions take

into account whether the dominant’s view was blocked while the food was placed. This could be

explained by the Third Principle. For the subordinate to predict that the dominant will not be able

to recover the food, it is sufficient to think: because the dominant did not encounter the food,

she will not be able to retrieve it.

‘In informed trials dominant individuals witnessed the experimenter hiding

food behind one of the occluders whereas in uninformed trials they could

not see the baiting procedure. In misinformed trials, dominants witnessed

the experimenter hiding food behind one of the occluders, and once the

dominant’s visual access was blocked, the experimenter switched the food

from its original location to the other occluder’ \citep{Hare:2001ph}.

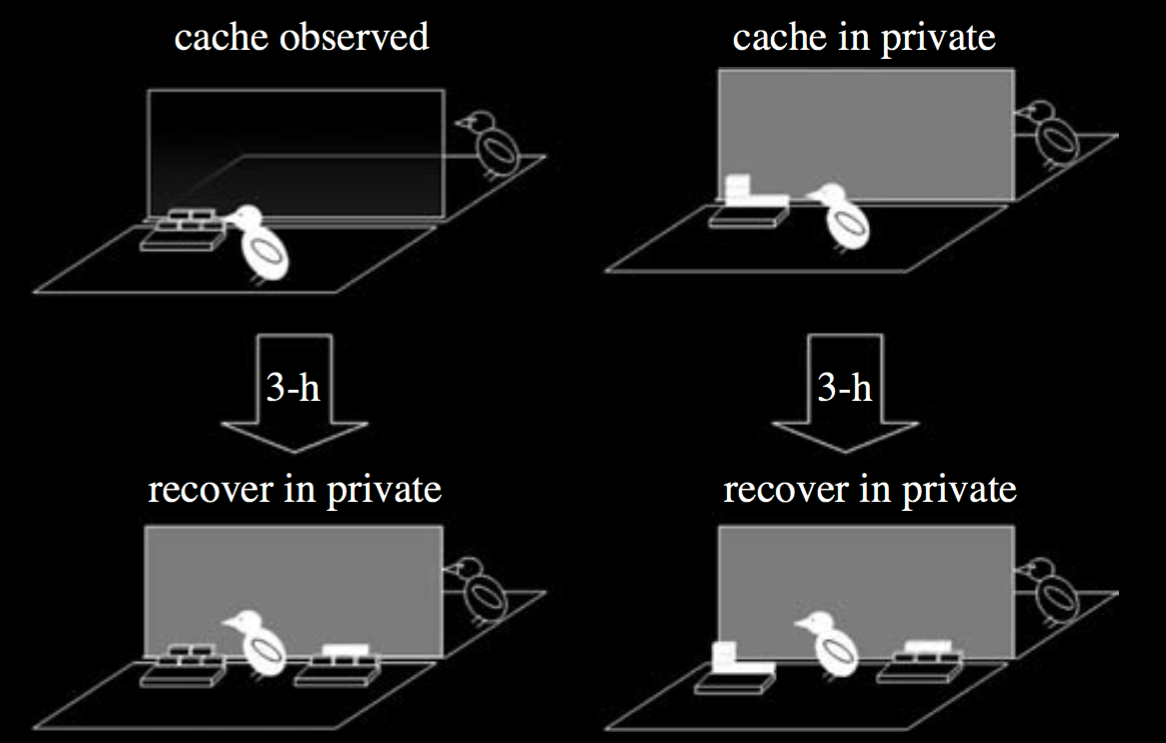

Clayton et al, 2007 figure 11

Clayton et al, 2007 figure 12

‘the jays were much more likely to re-cache if they had been observed by a conspecific while they

were caching than when they had cached in private. By re-caching items that the observer had seen

them cache, the cachers significantly reduce the chance of cache theft, as observers would be unable

to rely on memory to facilitate accurate cache theft’ \citep[p.~516]{Clayton:2007fh}.

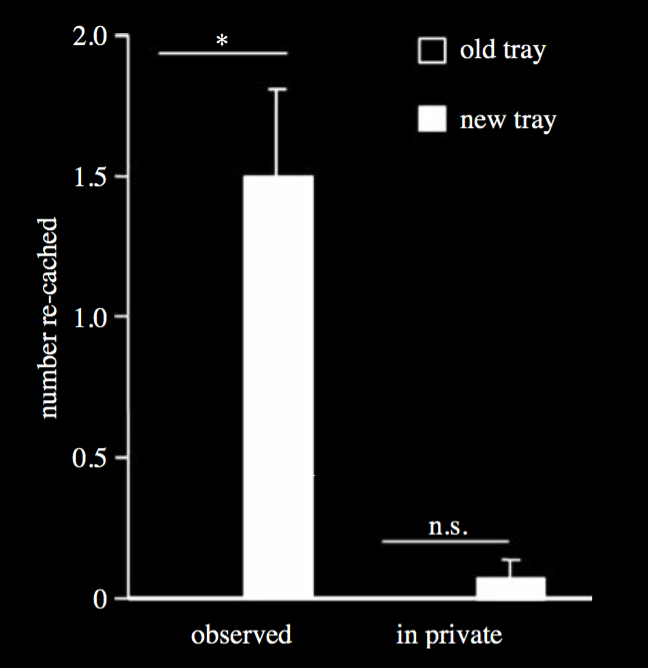

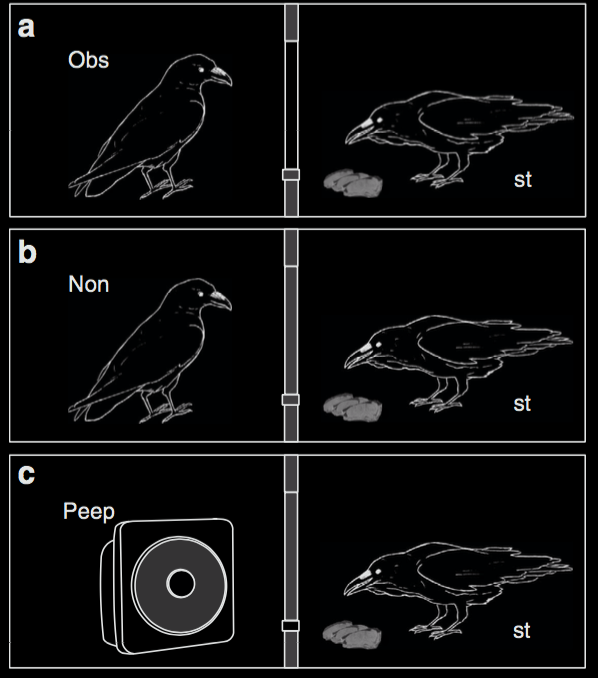

Bugnyar et al, 2016 figure 1

First show that window open vs window closed affects caching behaviour.

Then familiarise ravens with the peephole, letting them use it while humans

cache and letting them ‘steal’ the human-cached food.

Now test them by allowing them to cache when there’s apparently (from the sound,

which is actually a recording)

a raven on the other side.

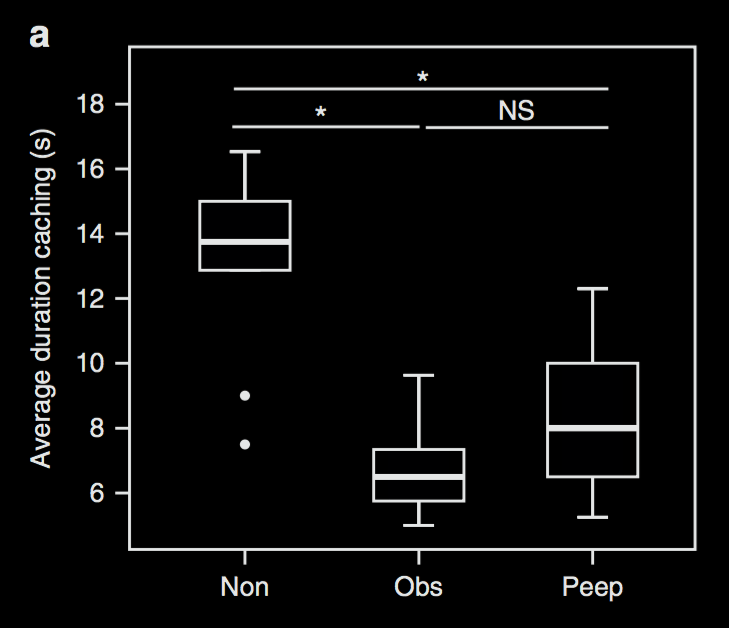

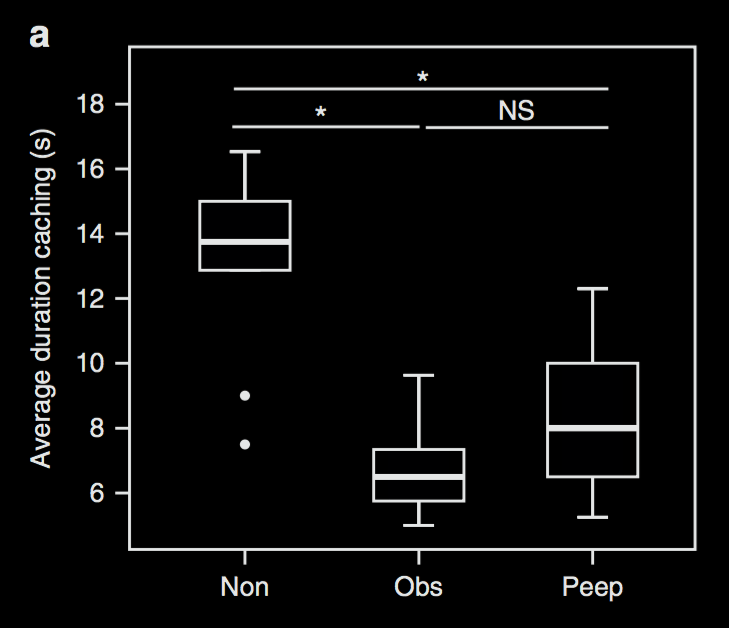

Bugnyar et al, 2016 figure 2a

Conclusion 1:

‘Peephole designs can allow researchers to overcome the confound of gaze cues’ \citep{bugnyar:2016_ravens}.

‘ravens can transfer knowledge from their own experience in a novel context---using peepholes to look

into an adjacent room---to a caching situation in which they can hear but not see a conspecific in that

room’ \citep{bugnyar:2016_ravens}.

Bugnyar et al, 2016 figure 1

Which action a chimp or jay predicts another will perform

depends to some extent on

what the other sees, knows or believes.

Question 1: Tracking to Representing

\section{Question 1: Tracking to Representing}

How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing?

| track | by representing |

| toxicity | odour |

| visibility | line-of-sight |

belief | ? |

To say that someone tracks beliefs does not entail saying that she represents beliefs.

In general, you can track something by representing something else.

Note that this complication is not supposed to show that we cannot make

the inference from tracking to mindreading.

After all, such inferences are not supposed to be deductive.

Nor do I intend to suggest that we should somehow find a different inference

which is deductive.

Instead my point is simply this: as the inference is not deductive, there are bound

to be tricky questions about how the observations support conclusions about tracking.

[LATER: one further complication will be that there are multiple models of minds and actions.]

Which action a chimp or jay predicts another will perform

depends to some extent on

what the other sees, knows or believes.

This is directly evidence for tracking ...

... but what about representing?

Mindreading requires representing

‘In saying that an individual has a theory of mind, we mean that the individual [can ascribe] mental states’

Premack & Woodruff, 1978 p. 515

Some don’t see a gap here ...

‘Comparative psychologists test for mindreading in non-human animals by determining whether they detect the presence and absence of particular cognitive states in a wide variety of circumstances.’

They eliminate potential confounding variables by ensuring that there is no one

observable state to which subjects might be responding’

\citep[p.~487]{halina:2015_there}.

Halina, 2015 p. 487

mindreading = using a theory of mind.

So mindreading involves representing mental states

detect = track

So Halina is inferring representing from tracking.

apes track beliefs ∴ they are mindreaders ?

For the purposes of this talk, I am going to assume that we can make this inference,

at least in some circumstances.

But since

representing does not logically entail tracking,

I don’t think it’s at all straightforward ...

Three questions:

\begin{enumerate}

\item How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing?

\item Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

\item Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes

but not always automatic? (And how could

belief-tracking ever be automatic if it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?)

\end{enumerate}

Q1

How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing models?

Q2

Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

Q3

Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes but not always automatic? How could belief-tracking be automatic given evidence that it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?

To stress: this is a genuine question. The assumption is that you can infer representing

from tracking. What we need, I think, is a clearer idea of how such inferences might succeed.

Requirement 1: Diversity in Strategies

Should we conclude that all animals which can track mental states are doing so by virtue of

representing them?

Two versions of this objection: (a) cross-species:

How confident are we that ringtailed lemurs are doing what chimpanzees are doing?

(b) within an individual:

In humans and other animals, tracking mental states likely involves many different

processes, including plenty of which that rely on simple cues.

Requirement 1:

We need a theory that allows us to distinguish mental state tracking underpinned

by mindreading from other forms of mental state tracking

Requirement 2: Models

The second question concerns how various individuals (or systems within them)

model minds and actions.

Let me explain with an illustration ...

‘chimpanzees understand … intentions … perception and knowledge,

‘chimpanzees probably do not understand others in terms of a fully human-like belief–desire

psychology’

Call & Tomasello, 2008 p.~191

‘chimpanzees understand … intentions … perception and knowledge,’ but ‘chimpanzees probably do not

understand others in terms of a fully human-like belief–desire psychology’

\citet[p.~191]{Call:2008di}.

After claiming that ‘chimpanzees understand … intentions … perception and knowledge,’

\citet{Call:2008di} qualify their claim by adding that ‘chimpanzees probably do not understand

others in terms of a fully human-like belief–desire psychology’ (p.~191).

This is true.

The emergence in human development of the most sophisticated abilities to represent mental states

probably depends on rich social interactions involving conversation about the mental

\citep{Slaughter:1996fv, peterson:2003_opening, moeller:2006_relations}, on linguistic abilities

\citep{milligan:2007_language,kovacs:2009_early},

(\citet[p.~760]{moeller:2006_relations}: ‘Our results provide support for the concept that access

to conversations about the mind is important for deaf children’s ToM development, in that there was

a significant relationship between maternal talk about mental states and deaf children’s

performance on verbal ToM tasks.’)

and on capacities to attend to, hold in mind and inhibit things \citep{benson:2013_individual,

devine:2014_relations}.

These are all scarce or absent in chimpanzees and other nonhumans.

So it seems unlikely that the ways humans at their most reflective represent mental states will

match the ways nonhumans represent mental states.

Reflecting on how adult humans talk about mental states is no way to understand how others

represent them.

But then what could enable us to understand how nonhuman animals represent mental states?

Requirement 2: Models

How do chimps or jays variously model minds and actions?

‘Nonhumans represent mental states’ is not a hypothesis

... or at least not one that generates readily testable predictions.

‘the core theoretical problem in ... animal mindreading is that ... the conception of mindreading that dominates the field ... is too underspecified to allow effective communication among researchers’

‘the core theoretical problem in contemporary research on animal mindreading is

that ... the conception of mindreading that dominates the field

... is too underspecified to allow effective communication among researchers,

and reliable identification of evolutionary precursors of human mindreading through

observation and experiment.’

\citep[p.~321]{heyes:2014_animal}

Heyes (2015, 321)

What does Heyes mean?

How confident should we be that we know how adult humans model minds and actions?

Philosophical methods

(Previous issue: how accurate are humans’ models of minds and actions?;

this issue: how confident should we be that we know how they model minds and actions?)

informal observation,

guesswork (‘intuition’),

imagination (including for ‘thought experiments’),

reasoning and argument,

and elegance

Aside ...

we don’t know much about adults humans’ mindreading abilities

‘Nonhumans represent mental states’ is not a hypothesis

... or at least not one that generates readily testable predictions.

‘the core theoretical problem in ... animal mindreading is that ... the conception of mindreading that dominates the field ... is too underspecified to allow effective communication among researchers’

‘the core theoretical problem in contemporary research on animal mindreading is

that ... the conception of mindreading that dominates the field

... is too underspecified to allow effective communication among researchers,

and reliable identification of evolutionary precursors of human mindreading through

observation and experiment.’

\citep[p.~321]{heyes:2014_animal}

Heyes (2015, 321)

How can we more fully specify mindreading?

Three questions:

\begin{enumerate}

\item How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing?

\item Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

\item Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes

but not always automatic? (And how could

belief-tracking ever be automatic if it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?)

\end{enumerate}

Q1

How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing models?

Q2

Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

Q3

Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes but not always automatic? How could belief-tracking be automatic given evidence that it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?

Requirement 1: Diversity in strategies

Requirement 2: Models

Question 2: Dissociations

\section{Question 2: Dissociations}

Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

second complication : dissociations in performance

‘the present evidence may constitute an implicit understanding of belief’

\citep[p.~113]{krupenye:2016_great}

Krupenye et al, 2016 p. 113

| study | type | success? |

| Call et al, 1999 | object choice (coop) | fail |

| Krachun et al, 2009 | ‘chimp chess’

(competitive, action) | fail |

| Krachun et al, 2009 | ‘chimp chess’

(competitive, gaze) | pass A,

fail B |

| Krachun et al, 2010 | change of contents | fail |

| Krupenye et al, 2017 | anticipatory looking

(2 scenarios) | pass both |

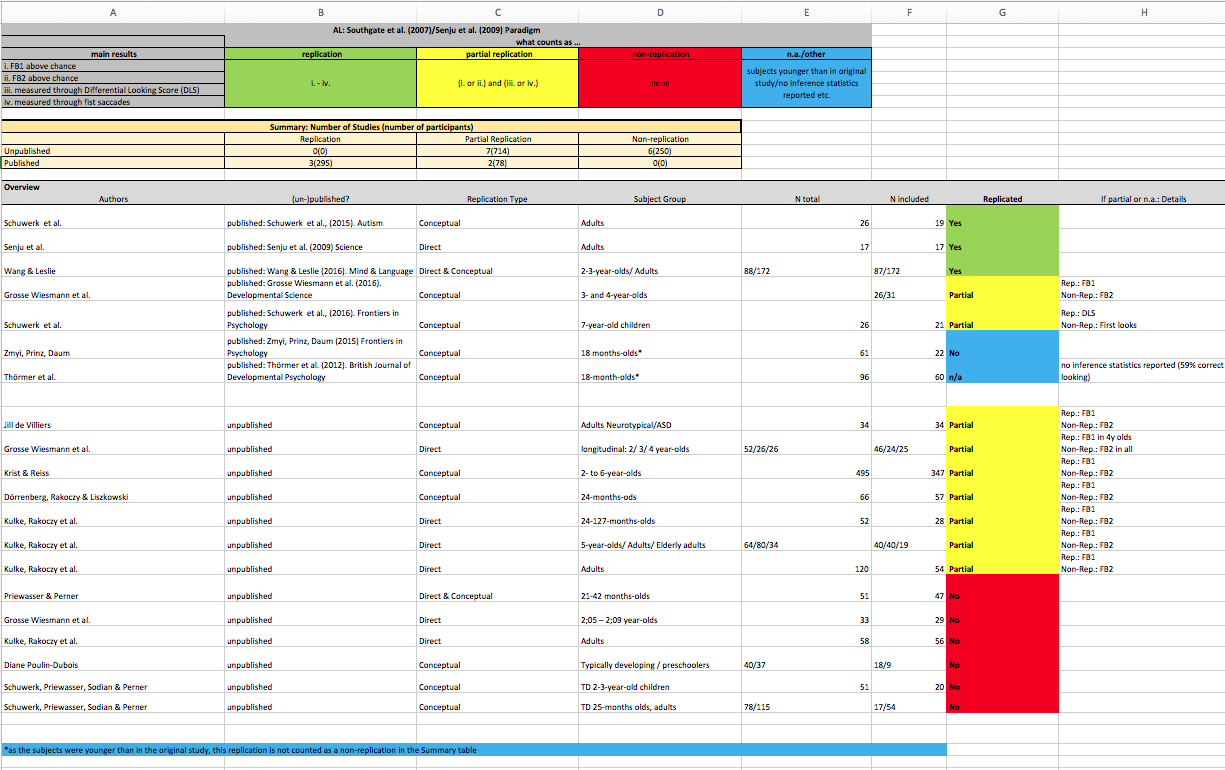

Commenting on their success in showing that great apes can track false beliefs,

Krupenye et al comment that ...

Why do they say ‘implicit’?

I think it’s because they expect dissociations: just as there are dissociations among different

measures of mindreading in adults, and developmental dissociations, so it is plausible that there

will turn out to be dissociations concerning the tasks that adult humans and adult nonhumans can

pass.

Indeed, we can see signs of dissociations if we go back to earlier work with great apes by Karla

Krachun and colleagues ...

Invoking implicit cannot explain the dissociations because you could have

just as well invoked

implicit for a completely different pattern of findings.

Three questions:

\begin{enumerate}

\item How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing?

\item Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

\item Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes

but not always automatic? (And how could

belief-tracking ever be automatic if it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?)

\end{enumerate}

Q1

How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing models?

Q2

Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

Q3

Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes but not always automatic? How could belief-tracking be automatic given evidence that it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?

So now we have a second question to answer

We shouldn’t draw conclusions about mindreading from tracking before

we can answer at least these two questions.

Ooops, I almost forgot to mention dissociation in humans ...

I’m not going to mention infants much,

but we’ll see evidence that’s relevant to adults later

\section{Question 3: Automaticity}

In adults, mindreading is sometimes entirely a consequence of relatively automatic

processes and sometimes not.

Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes

but not always automatic? (And how could

belief-tracking ever be automatic if it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?)

Are human adults’ abilities to track others’ beliefs automatic?

For our purposes, a process is \emph{automatic} to the degree that whether it occurs is independent of

its relevance to the particulars of the subject's task, motives and aims.

‘Automatic mindreading’ is short for ‘mindreading that is a consequence of

automatic processes only.’

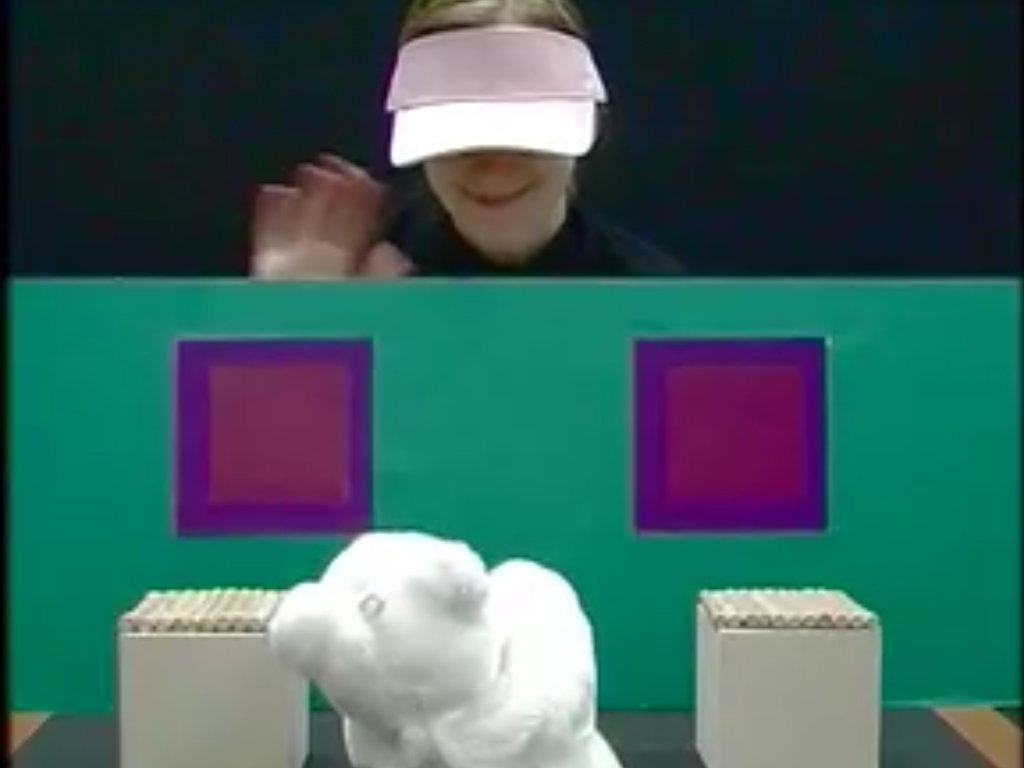

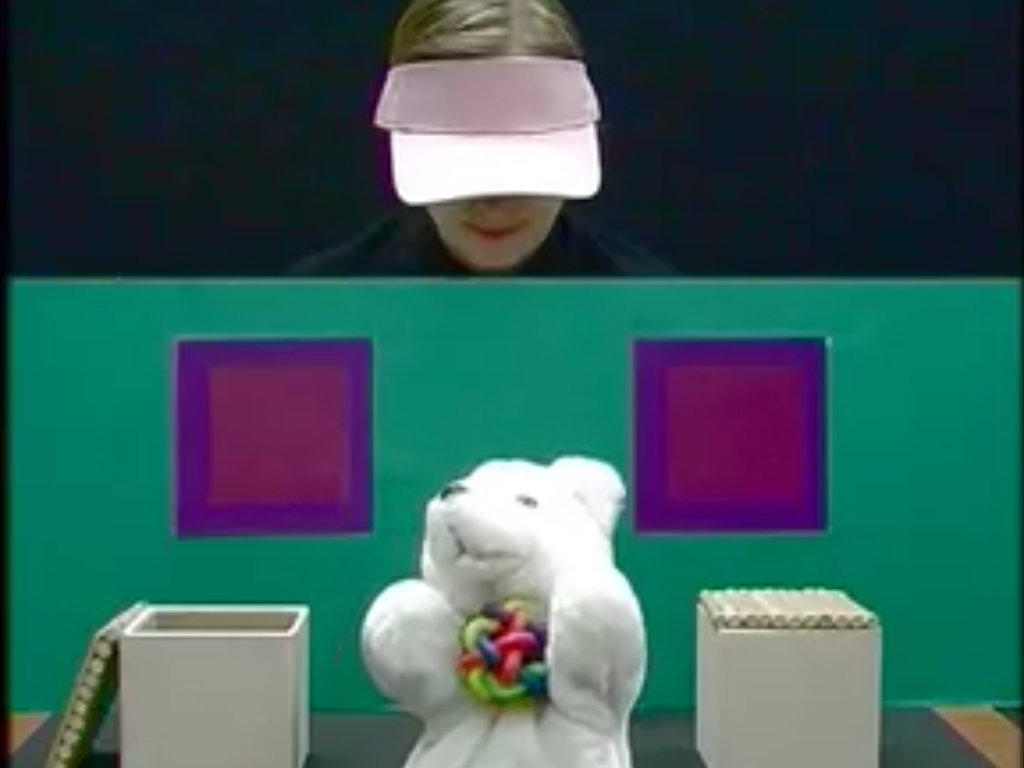

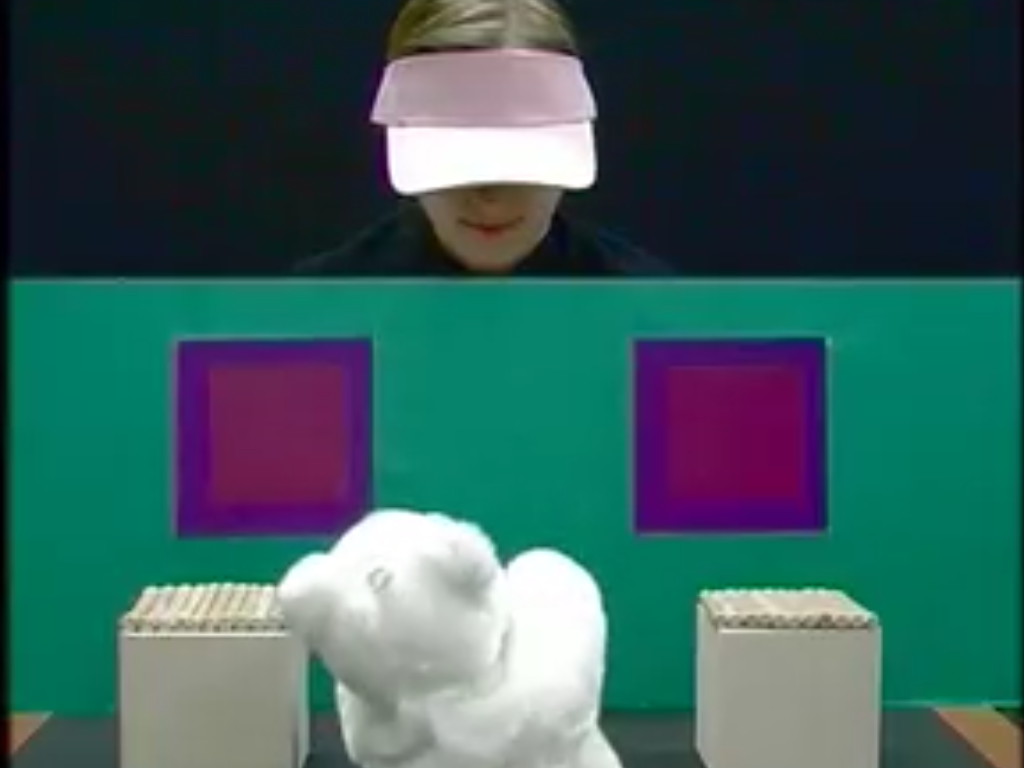

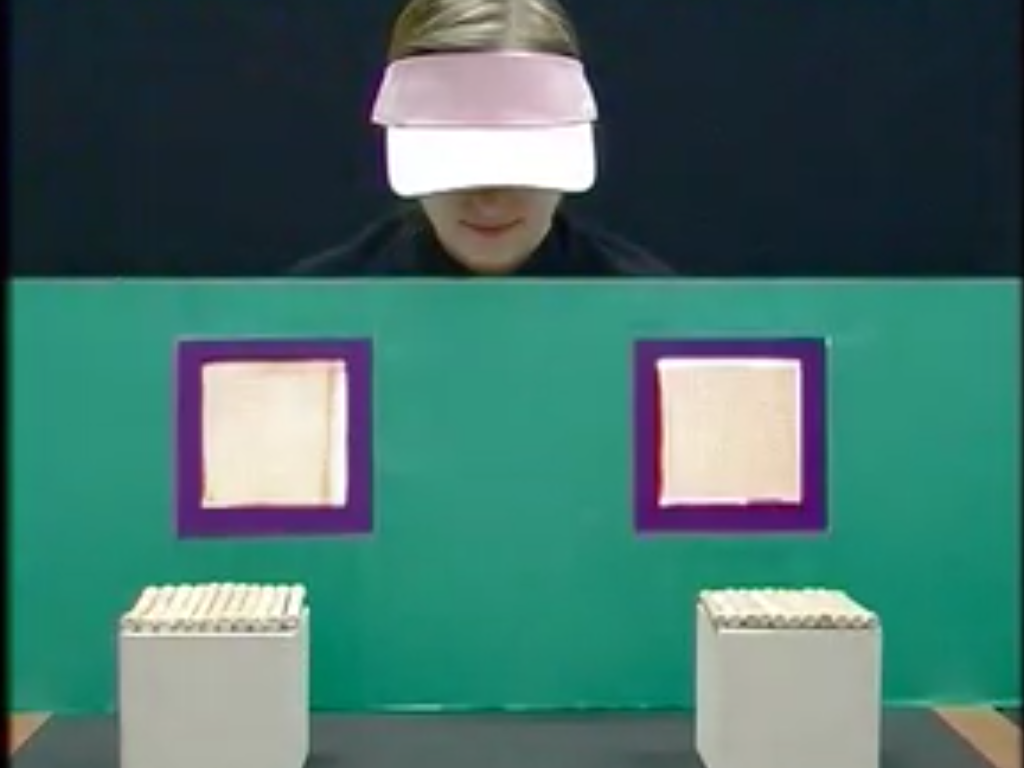

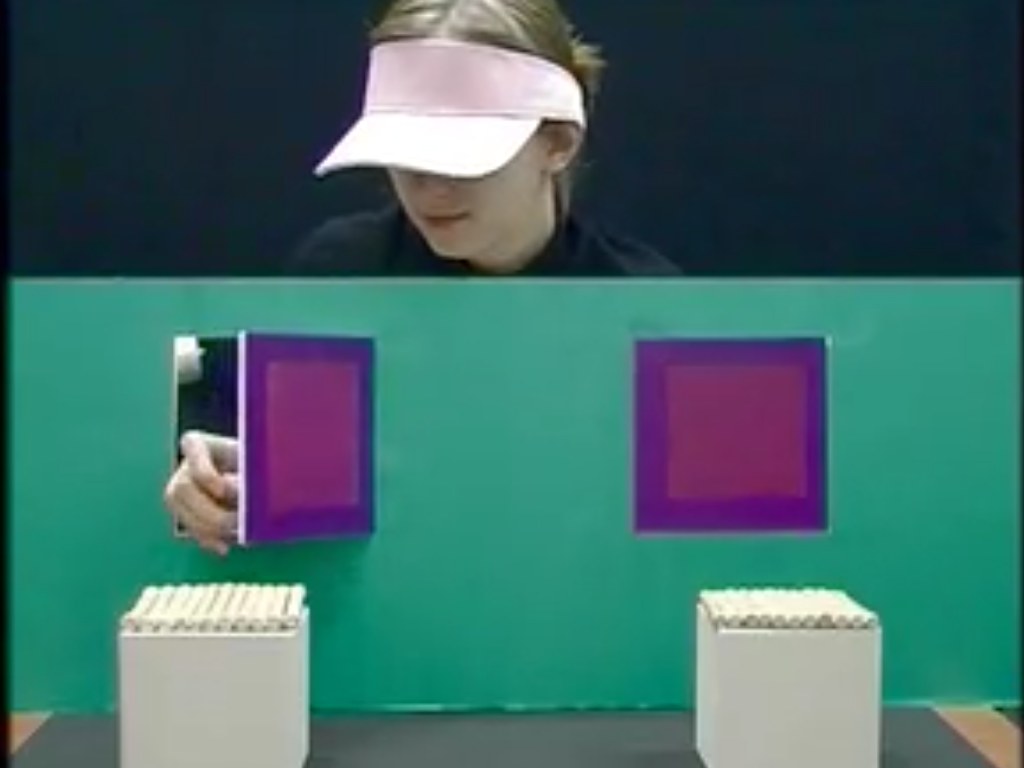

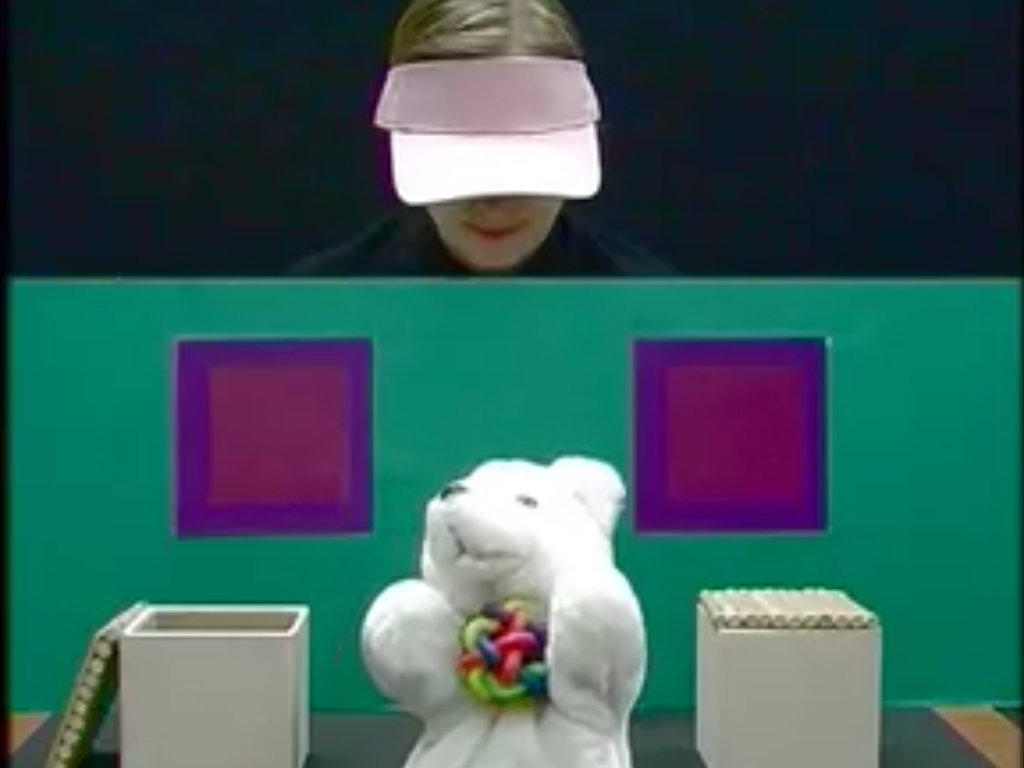

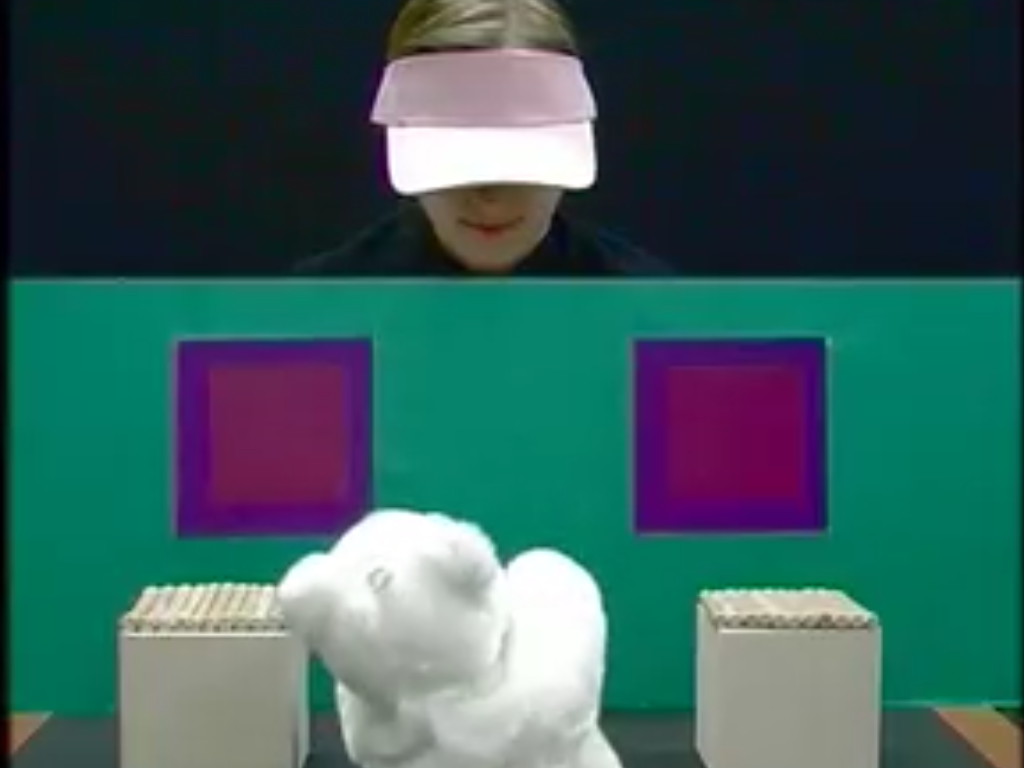

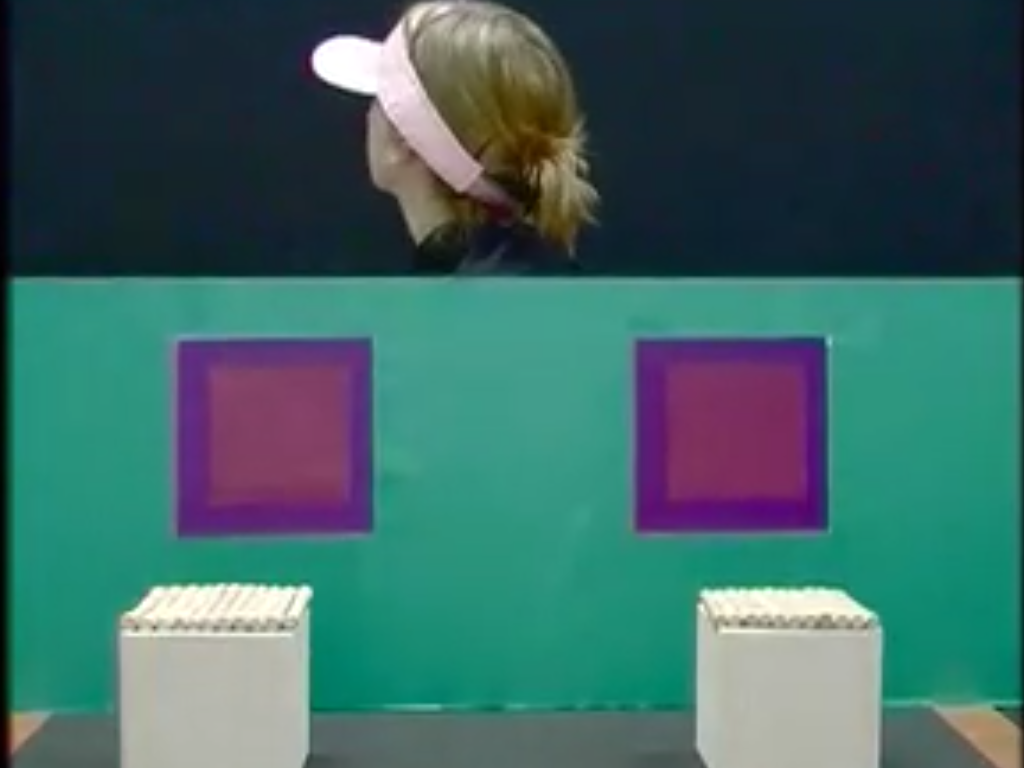

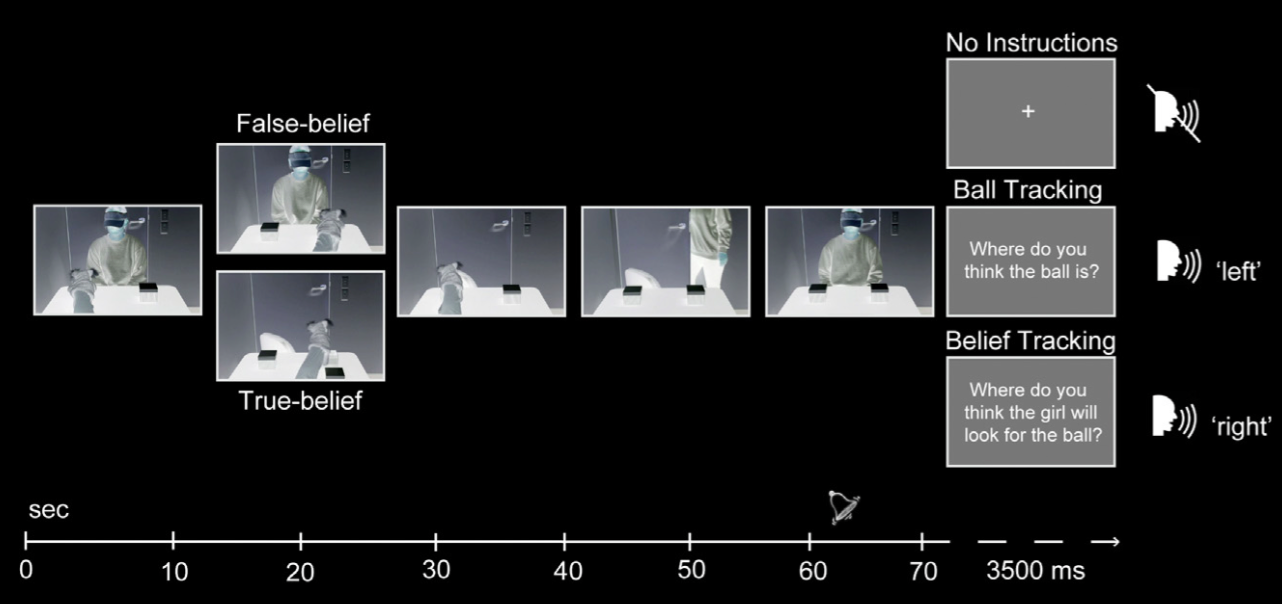

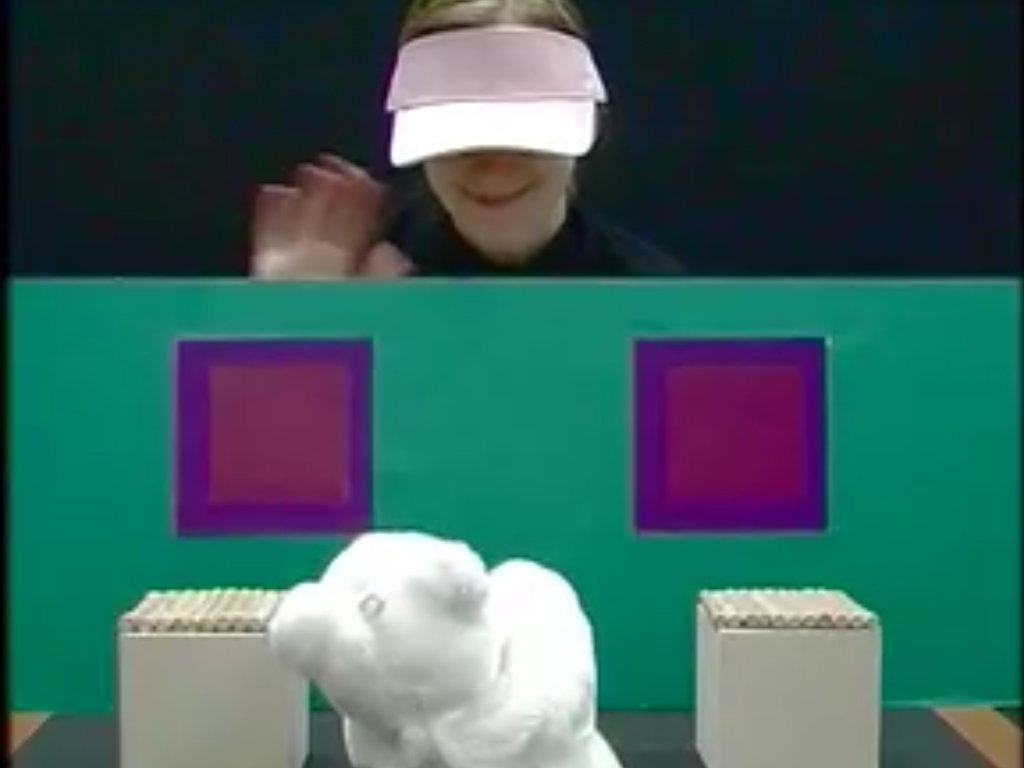

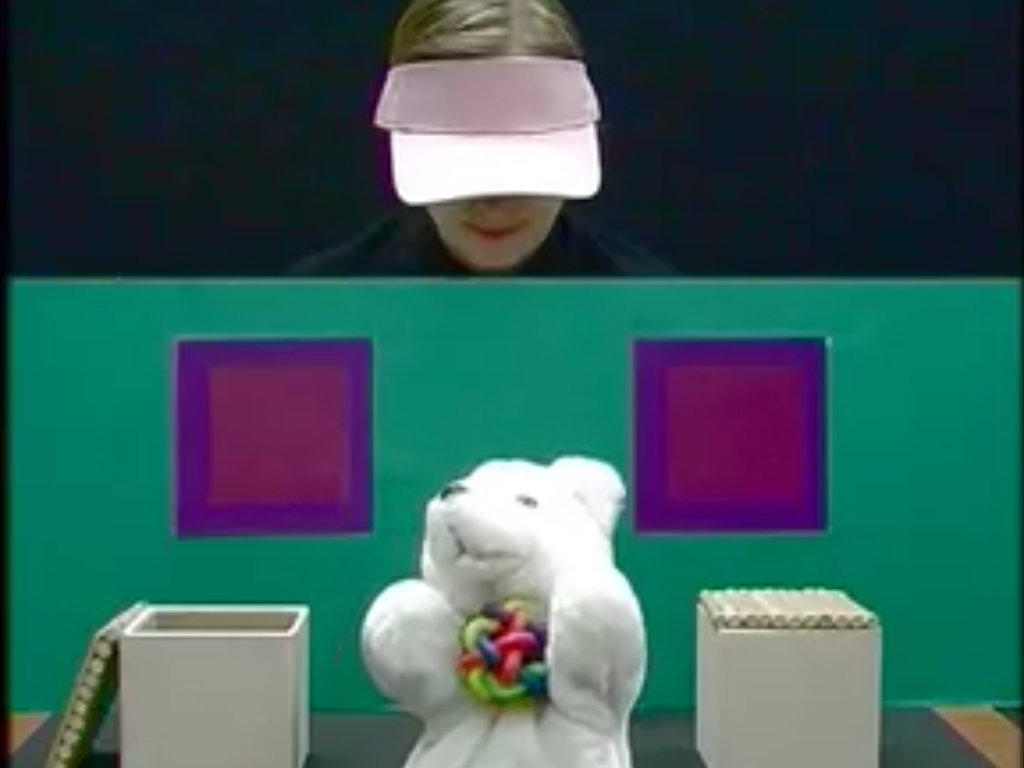

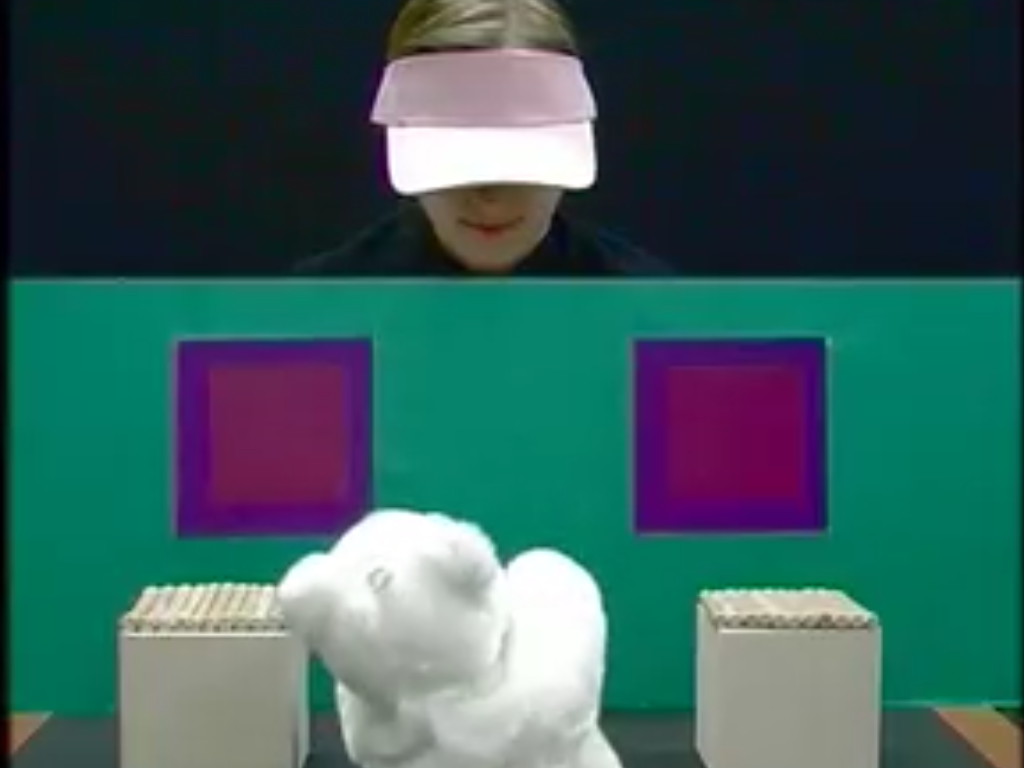

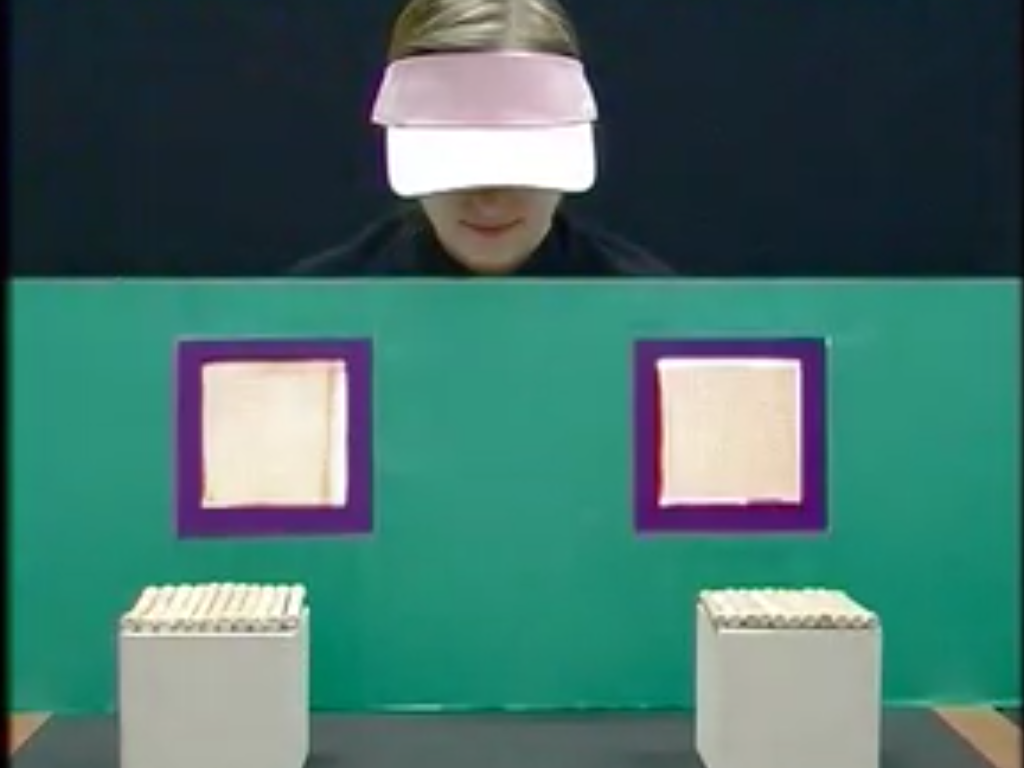

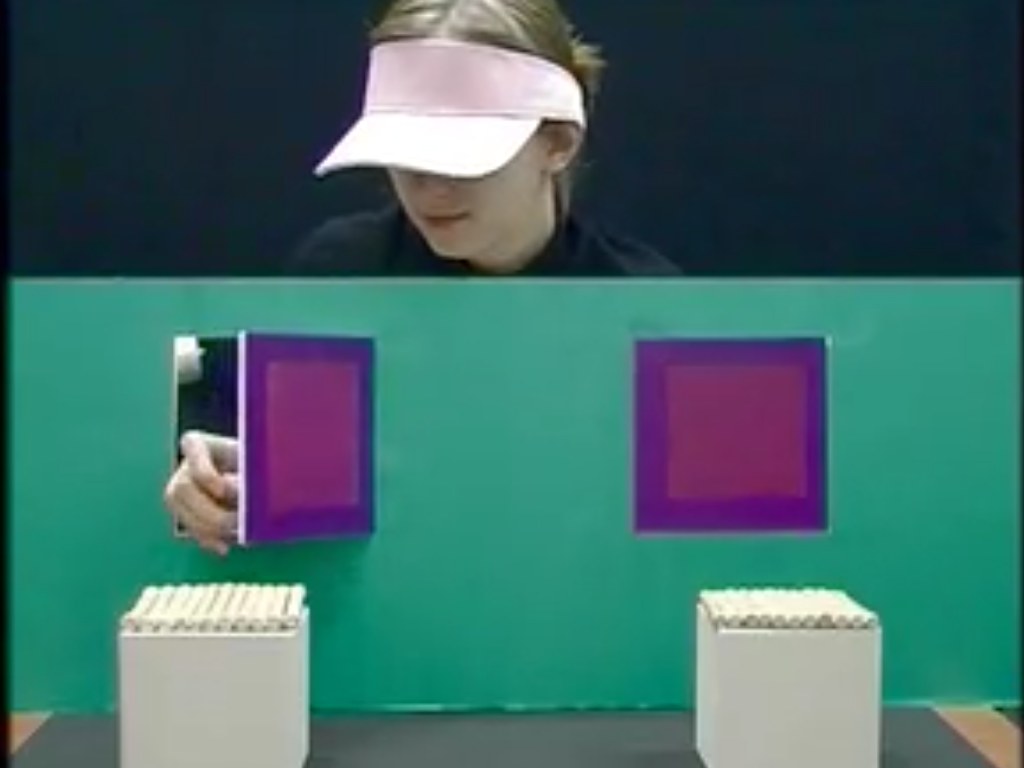

\citet{Southgate:2007js} created an anticipatory looking false belief task, originally

for use with two-year-olds, which has been adapated to provide evidence for automatic

false belief tracking.

There is evidence that some mindreading in human adults is

entirely a consequence of relatively automatic processes

\citep{kovacs_social_2010,Schneider:2011fk,Wel:2013uq} and

that not all mindreading in human adults is

\citep{apperly:2008_back,apperly_why_2010,Wel:2013uq}.

Three questions:

\begin{enumerate}

\item How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing?

\item Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

\item Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes

but not always automatic? (And how could

belief-tracking ever be automatic if it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?)

\end{enumerate}

Q1

How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing models?

Q2

Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

Q3

Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes but not always automatic? How could belief-tracking be automatic given evidence that it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?

A process involves \emph{belief-tracking} if how processes of this type unfold

typically and nonaccidentally depends on facts about beliefs.

So belief tracking can, but need not, involve representing beliefs.

belief-tracking is sometimes but not always automatic

A process is \emph{automatic} to the degree that whether it occurs is independent of its

relevance to the particulars of the subject's task, motives and aims.

Or, carefully, does belief tracking in human adults depend only

on processes which are automatic?

There is now a variety of evidence that belief-tracking is sometimes and

not always automatic in adults. Let me give you just one experiment here

to illustrate.

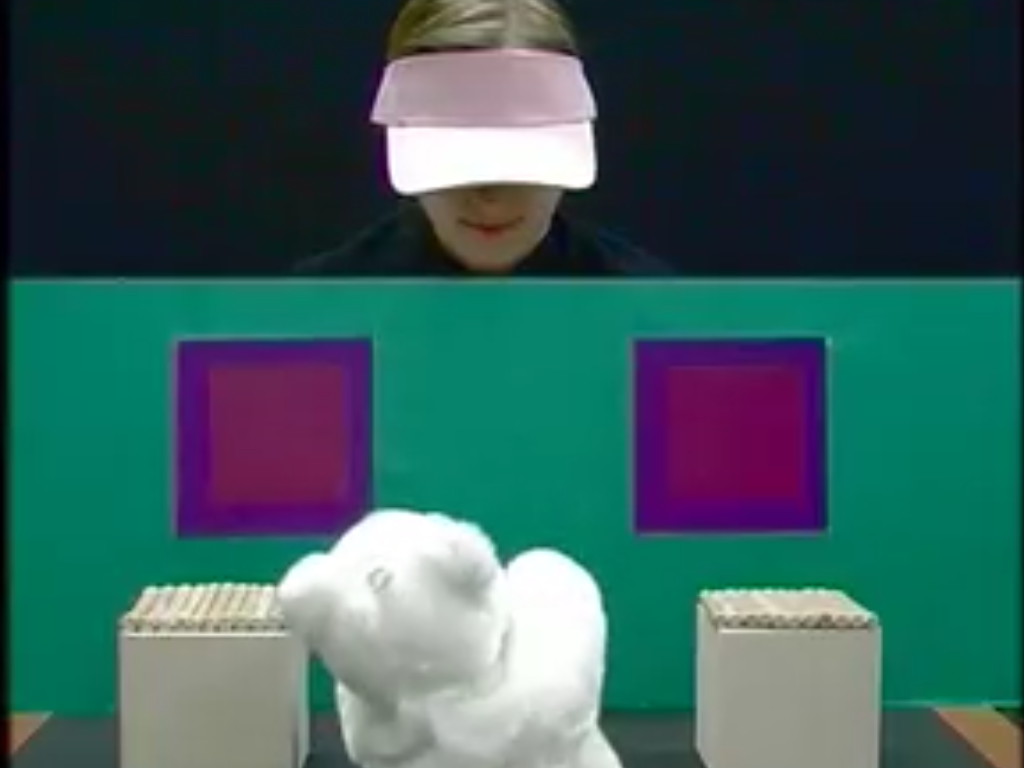

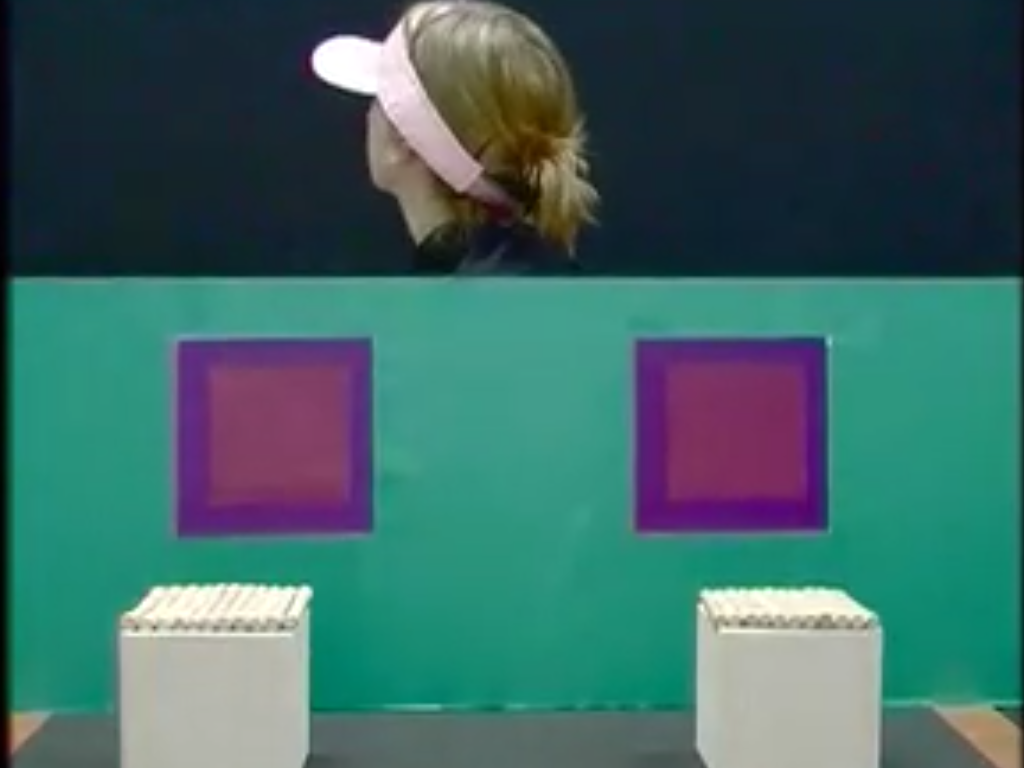

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Explain the southgate et al paradigm

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

Southgate et al, 2007; Senju et al, 2009 video S1

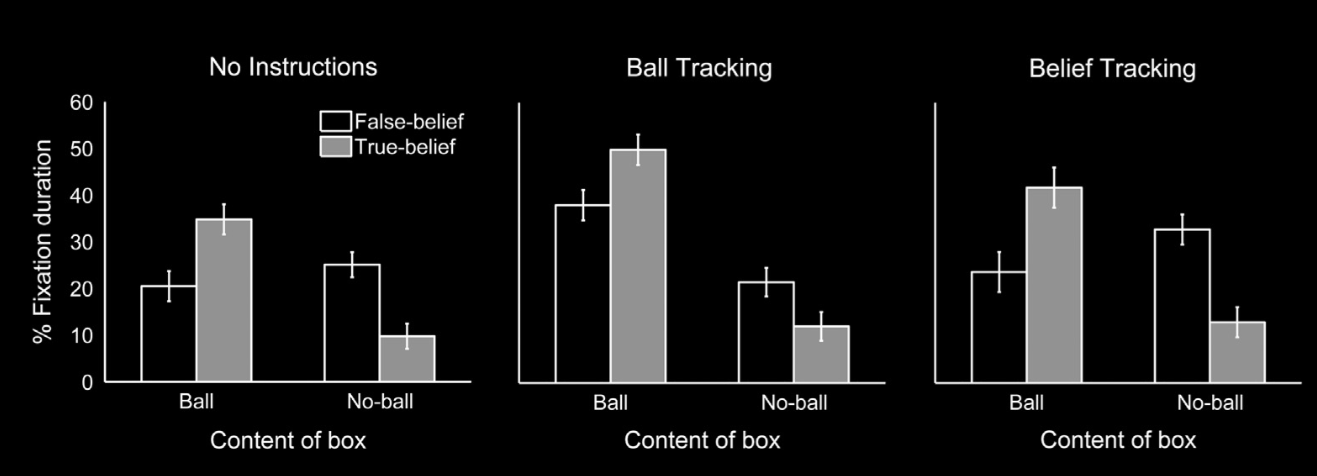

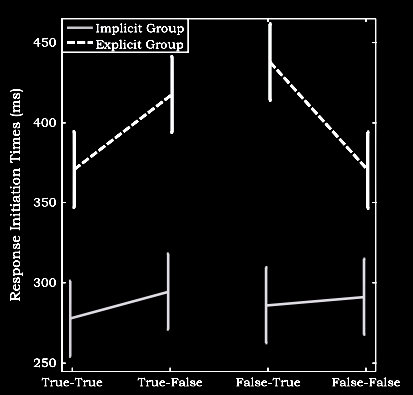

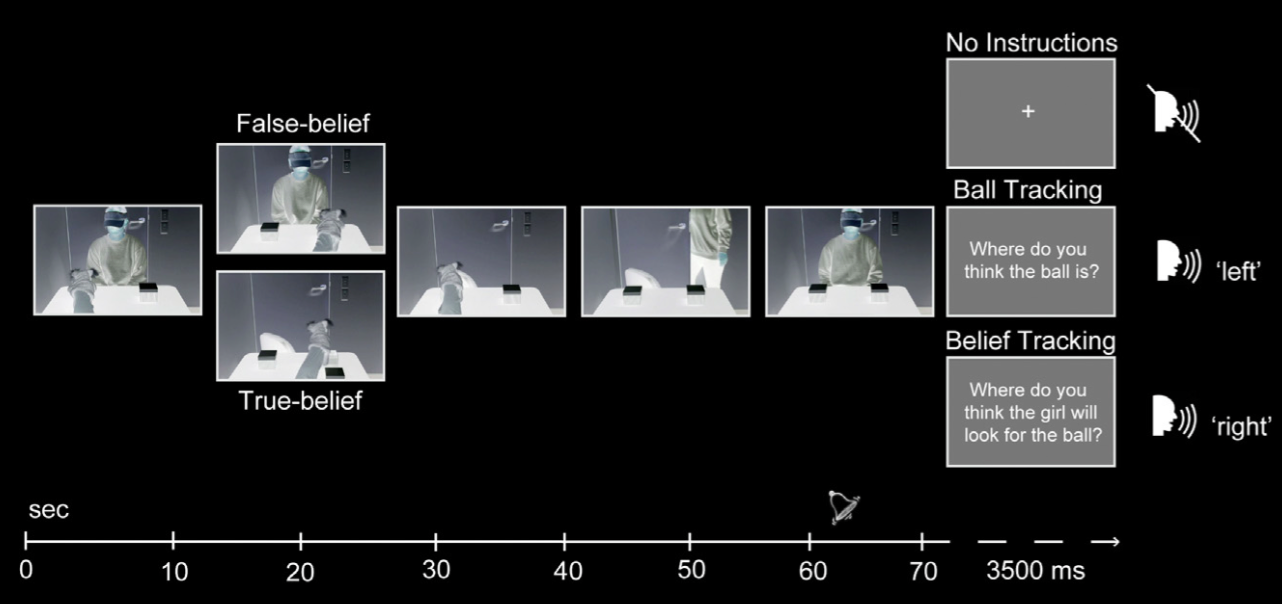

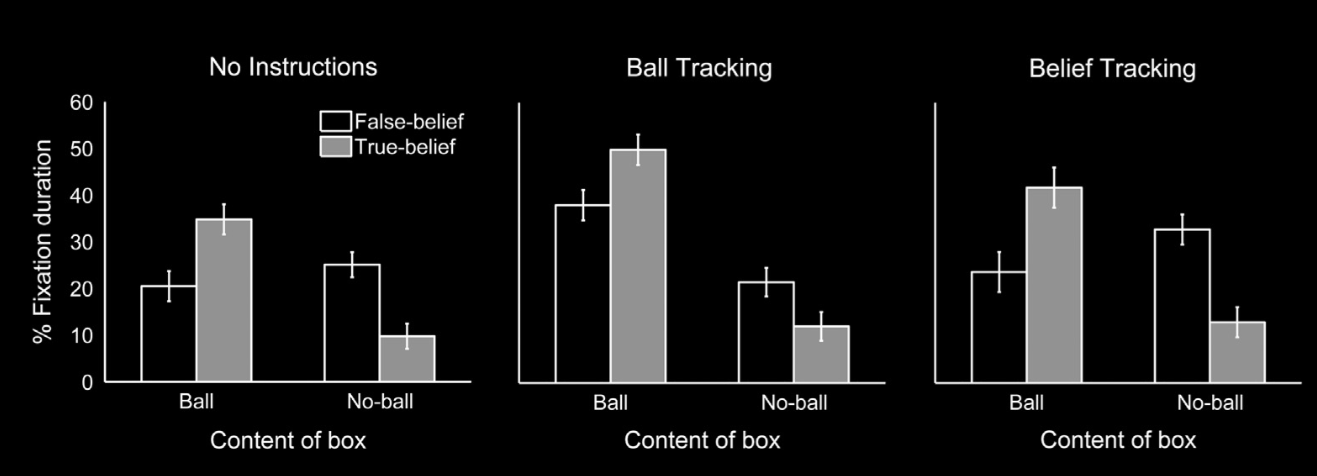

Schneider et al (2014, figure 1)

[skip this slide]

One way to show that mindreading is automatic is to give subjects a task which does not require tracking beliefs and then to compare their performance in two scenarios:

a scenario where someone else has a false belief, and a scenario in which someone else has a true belief.

If mindreading occurs automatically, performance should not vary between the two scenarios because others’ beliefs are always irrelevant to the subjects’ task and motivations.

Schneider et al (2014, figure 3)

[skip this slide]

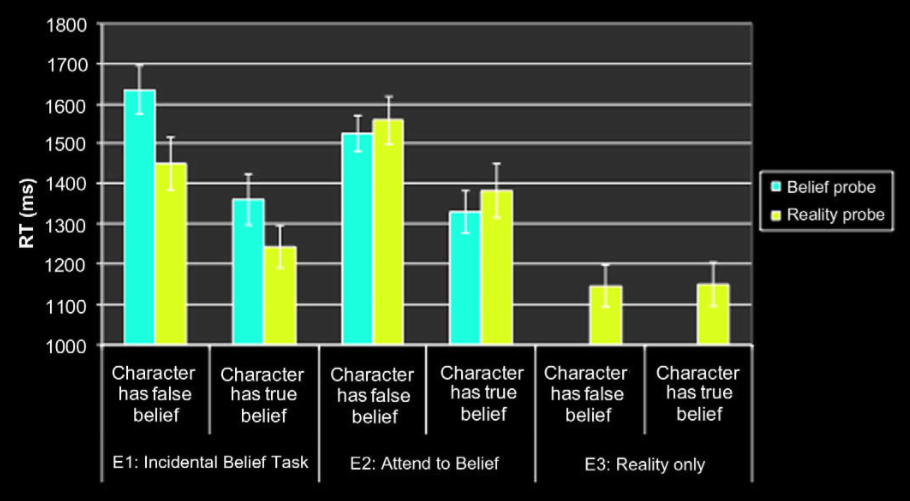

\citet{Schneider:2011fk} did just this.

They showed their participants a series of videos and instructed them to detect when a figure waved or, in a second experiment, to discriminate between high and low tones as quickly as possible.

Performing these tasks did not require tracking anyone’s beliefs, and the participants did not report mindreading when asked afterwards.

on experiment 1: ‘Participants never reported belief tracking when questioned in an open format after the experiment (“What do you think this experiment was about?”). Furthermore, this verbal debriefing about the experiment’s purpose never triggered participants to indicate that they followed the actor’s belief state’ \citep[p.~2]{Schneider:2011fk}

Nevertheless, participants’ eye movements indicated that they were tracking the beliefs of a person who happened to be in the videos.

In a further study, \citet{schneider:2014_task} raised the stakes by giving participants a task that would be harder to perform if they were tracking another’s beliefs.

So now tracking another’s beliefs is not only irrelevant to performing the tasks: it may actually hinder performance.

Despite this, they found evidence in adults’ looking times that they were tracking another’s false beliefs.

This indicates that ‘subjects … track the mental states of others even when they have instructions to complete a task that is incongruent with this operation’ \citep[p.~46]{schneider:2014_task} and so provides evidence for automaticity.%

\footnote{%

% quote is necessary to qualify in the light of their interpretation; difference between looking at end (task-dependent) and at an earlier phase (task-independent)?

%\citet[p.~46]{schneider:2014_task}: ‘we have demonstrated here that subjects implicitly track the mental states of others even when they have instructions to complete a task that is incongruent with this operation. These results provide support for the hypothesis that there exists a ToM mechanism that can operate implicitly to extract belief like states of others (Apperly & Butterfill, 2009) that is immune to top-down task settings.’

It is hard to completely rule out the possibility that belief tracking is merely spontaneous rather than automatic.

I take the fact that belief tracking occurs despite plausibly making subjects’ tasks harder to perform to indicate automaticity over spontaneity.

If non-automatic belief tracking typically involves awareness of belief tracking, then the fact that subjects did not mention belief tracking when asked after the experiment about its purpose and what they were doing in it further supports the claim that belief tracking was automatic.

}

Further evidence that mindreading can occur in adults even when counterproductive has been provided by \citet{kovacs_social_2010}, who showed that another’s irrelevant beliefs about the location of an object can affect how quickly people can detect the object’s presence,

and by \citet{Wel:2013uq}, who showed that the same can influence the paths people take to reach an object.

Taken together, this is compelling evidence that mindreading in adult humans sometimes involves automatic processes only.

‘Participants never reported belief tracking when questioned in an open format after the experiment

(“What do you think this experiment was about?”). Furthermore, this verbal debriefing about the

experiment’s purpose never triggered participants to indicate that they followed the actor’s belief

state’ \citep[p.~2]{Schneider:2011fk}

altercentric interference

belief-tracking is sometimes but not always automatic

aside: altercentric interference vs procative gaze

It’s good that we have both altercentric interference (which indicates that

the contents of beliefs are represented) and proactive gaze (which might

be taken to indicate an action prediction).

Altercentric interference indicates automaticity because it is counterproductive;

proactive gaze indicates automaticity because it occurs irrespective of

instructions.

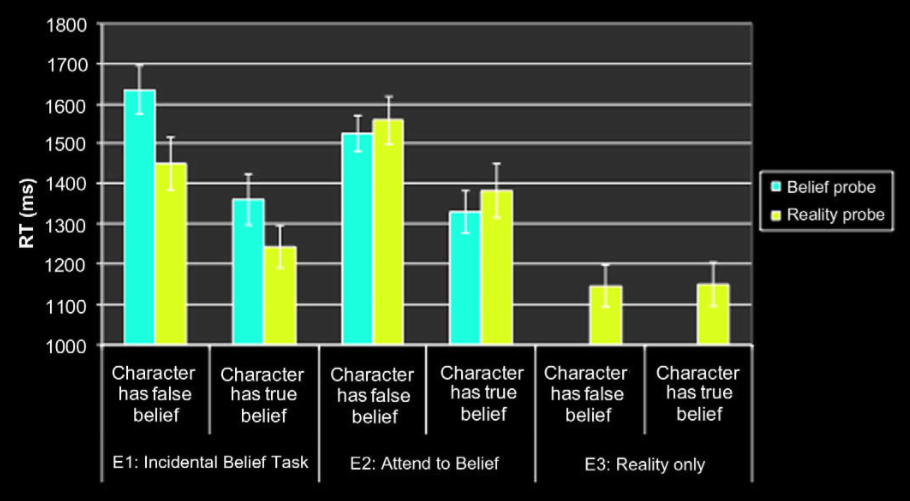

Back & Apperly (2010, fig 1, part)

This is the data for answers that required a ‘yes’ response.

So does all mindreading in adult humans involve only processes which are automatic?

No: it turns out that verbal responses in false belief tasks that are A-tasks are not typically a consequence of automatic belief tracking.

To show this, \citet{back:2010_apperly} instructed people to watch videos in which someone acquires a belief, either true or false, and then, after the video, asked them an unexpected question about the protagonist’s belief \citep[see also][]{apperly:2006_belief}.

They measured how long people took to answer this question.

Starting with the hypothesis that answering a question about belief involves automatic mindreading only,

they reasoned that the mindreading necessary to answer a question about belief will have occurred before the question is even asked.

Accordingly there should be no delay in answering an unexpected question about belief—or, at least, no more delay than in answering unexpected questions about any other facts that are automatically tracked.

But they found that people were slower to answer unexpected questions about belief than predicted.

Importantly this was not due to any difficulty with questions about belief as such: when such questions were expected, they were answered just as quickly as other, non-belief questions.

It seems that, when asked an unexpected question about another’s belief, people typically need time to work out what the other believes.

We must therefore reject the hypothesis that answering a question about belief involves automatic mindreading only.%

\footnote{%

\citet[ms~p.~9]{carruthers:2015_mindreading} objects (following \citealp{cohen:2009_encoding}) that these experiments are ‘not really about encoding belief but recalling it.’

Note that this objection is already answered by \citet[p.~56]{back:2010_apperly}.

}

belief-tracking is sometimes but not always automatic

-- can consume attention and working memory

-- can require inhibition

More evidence for automaticity and non-automaticity.

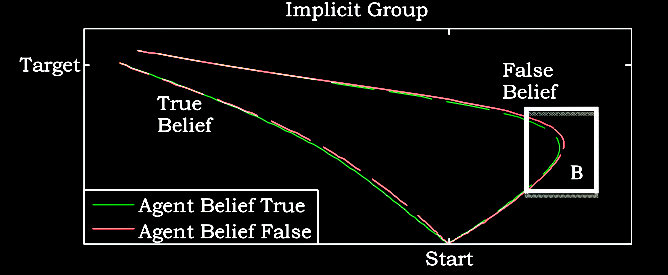

This is what you as subject see.

Actually you can't see this so well, let me make it bigger.

This is what you as subject see.

There is are two balls moving around, two barriers, and a protagonist who is looking on.

Your task is very simple (this is the 'implicit condition'): you are told to track one

of these objects at the start, and at the end you're going to have to use a mouse

to move a pointer to its location.

This is how the experiment progresses.

You can see that the protagonist leaves in the third

phase. This is the version of the sequence in which the protagonist has a true belief.

This is the version of the sequence in which the protagonist has a false belief.

(Because the balls swap locations while she's not absent.')

OK, so there's a simple manipulation: whether the protagonist has true or false beliefs,

and this is task-irrelevant: all you have to do is move the mouse to where one of the balls is.

Why is this interesting?

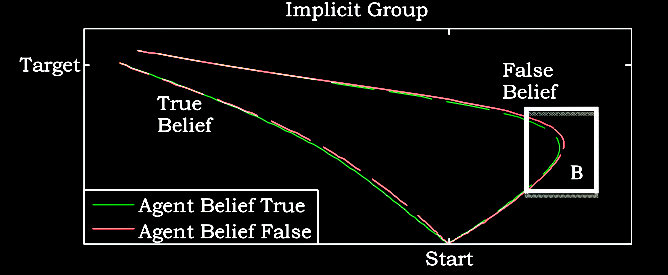

van der Wel et al (2014, figure 1)

Just look at the 'True Belief' lines (the effect can also be found when your belief

turns out to be false, but I'm not worried about that here.)

Do you see the area under the curve?

When you are moving the mouse,

the protagonist's false belief is pulling you away from the actual location

and towards the location she believes this object to be in!

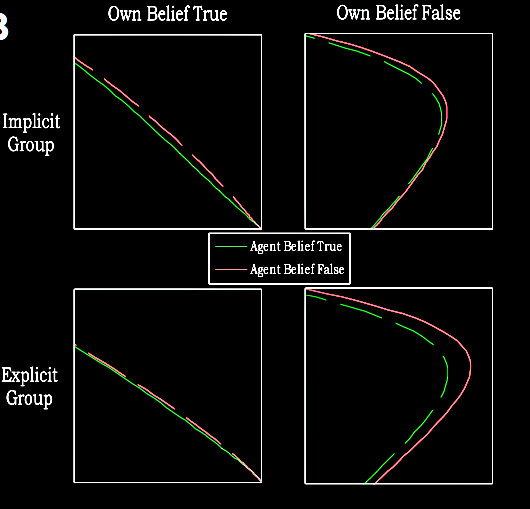

van der Wel et al (2014, figure 2)

Here's a zoomed in view. We're only interested in the top left box (implicit condition,

participant has true belief).

To repeat,

When you are moving the mouse,

the protagonist's false belief is pulling you away from the actual location

and towards the location she believes this object to be in!

van der Wel et al (2014, figure 2)

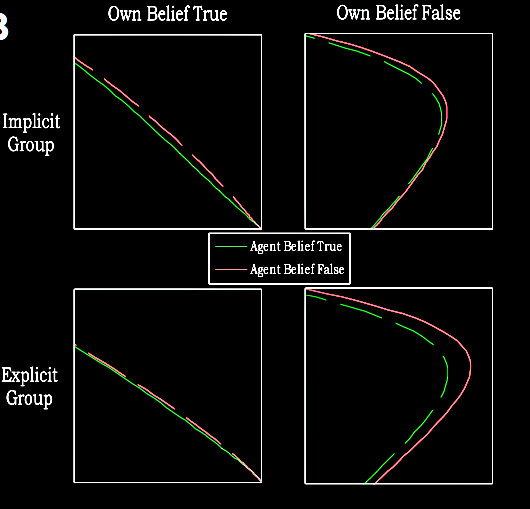

Using the same task, van der Wel et al also show that some processes are NOT automatic ...

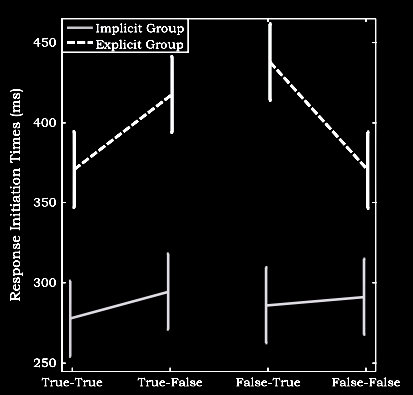

\citep[p.\ 132]{Wel:2013uq}:

‘In support of a more rule-based and controlled system, we found that response initiation times

changed as a function of the congruency of the participant’s and the agent’s belief in the

explicit group only. Thus, when participants had to track both beliefs, they slowed down

their responses when there was a belief conflict versus when there was not. The observation

that this result only occurred for the explicit group provides evidence for a controlled system.’

van der Wel et al (2014, figure 3)

Let me emphasise this because we'll come back to it later:

‘they slowed down their responses when there was a belief conflict versus when there was not’

Three questions:

\begin{enumerate}

\item How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing?

\item Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

\item Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes

but not always automatic? (And how could

belief-tracking ever be automatic if it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?)

\end{enumerate}

Q1

How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing models?

Q2

Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

Q3

Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes but not always automatic? How could belief-tracking be automatic given evidence that it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?