Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

12: Is There a Role for Motor Processes in Mindreading?

[email protected]

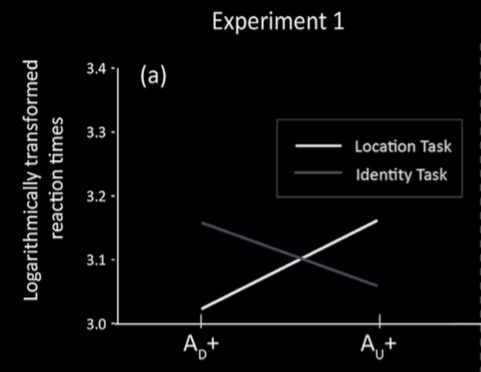

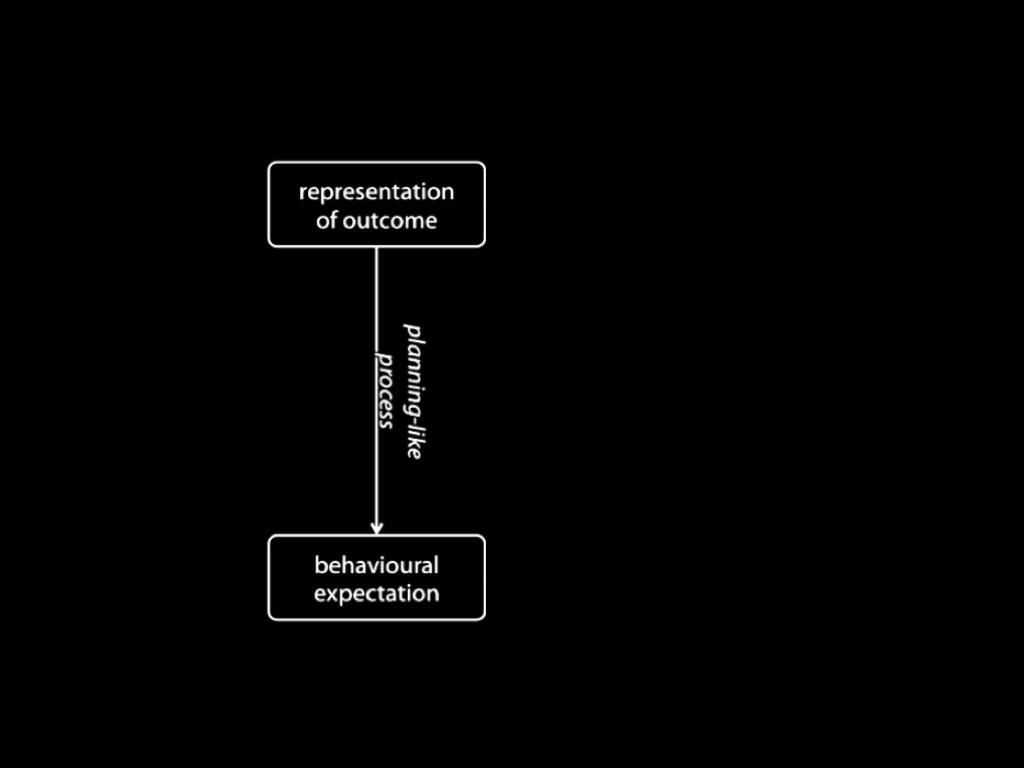

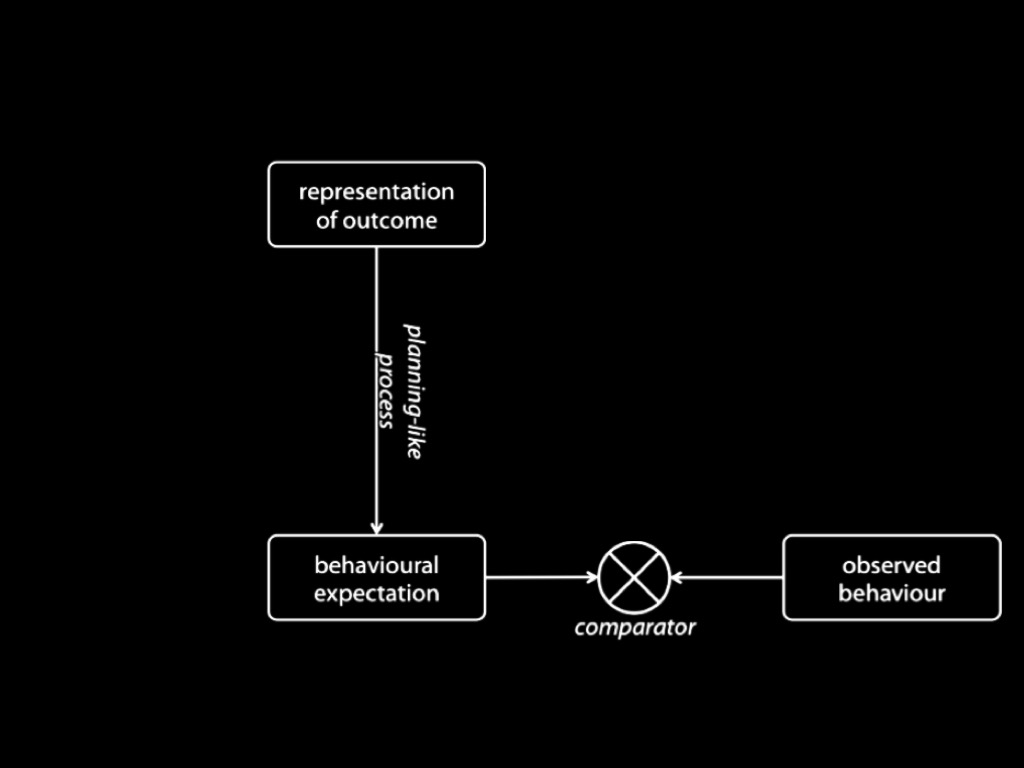

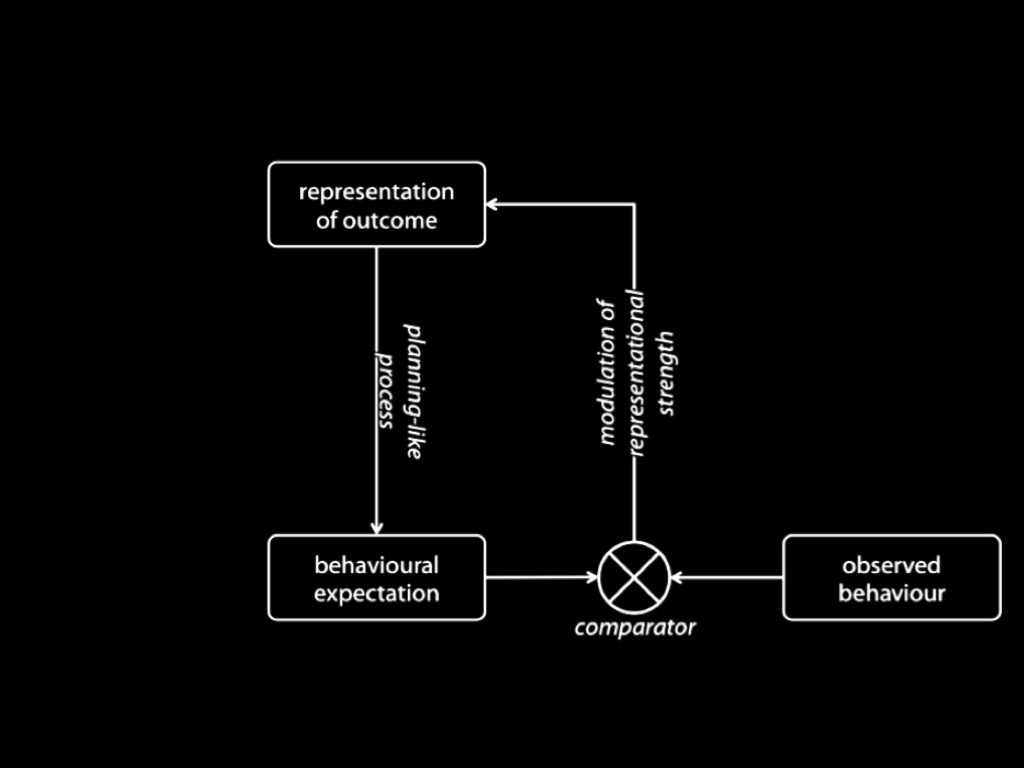

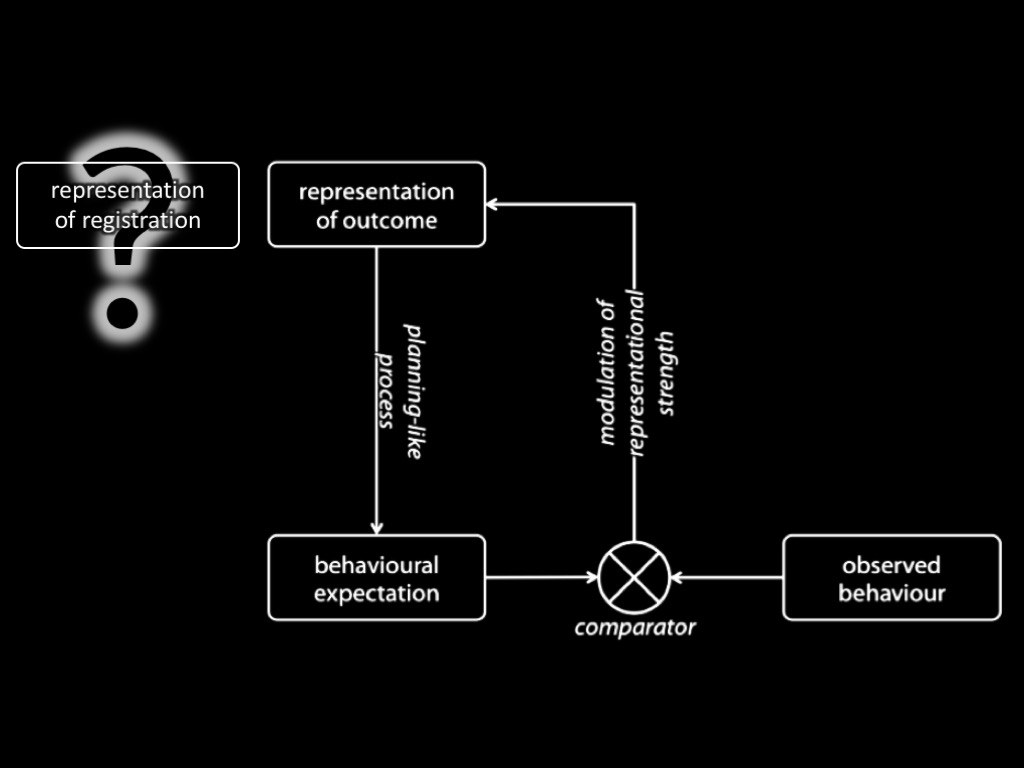

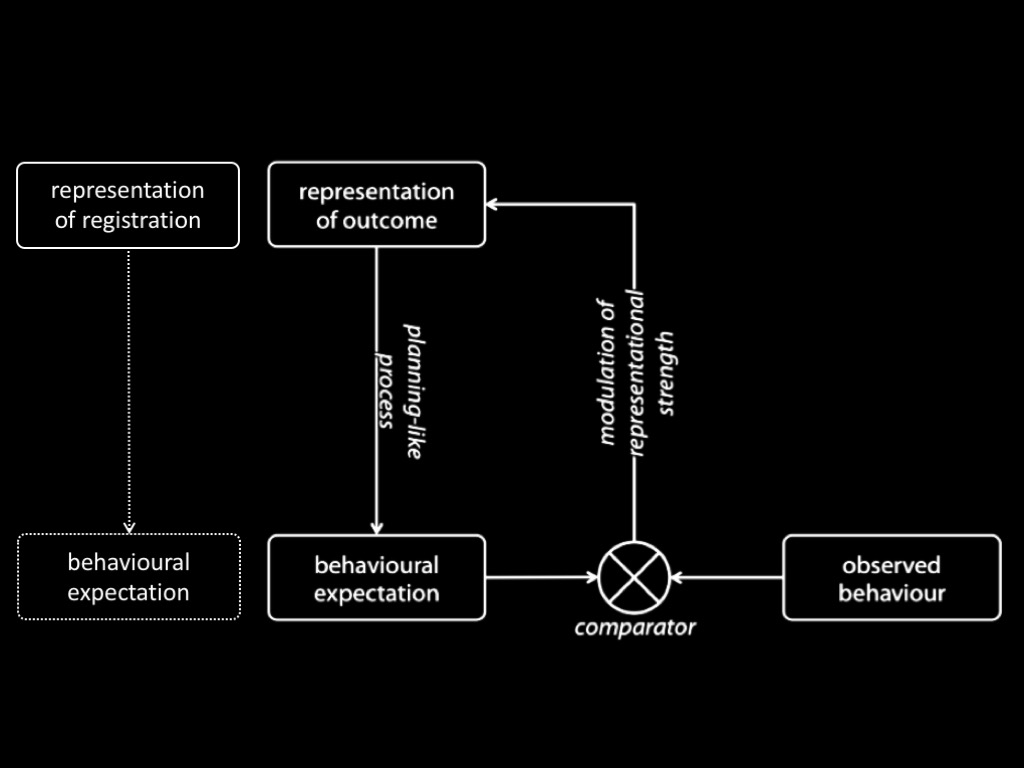

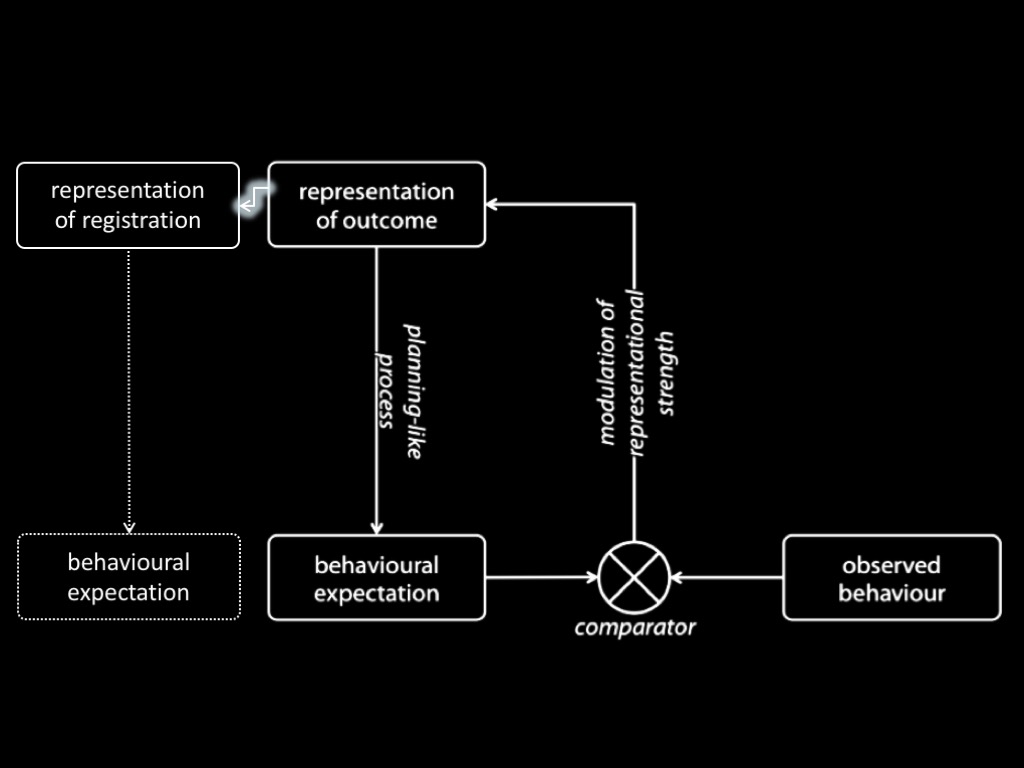

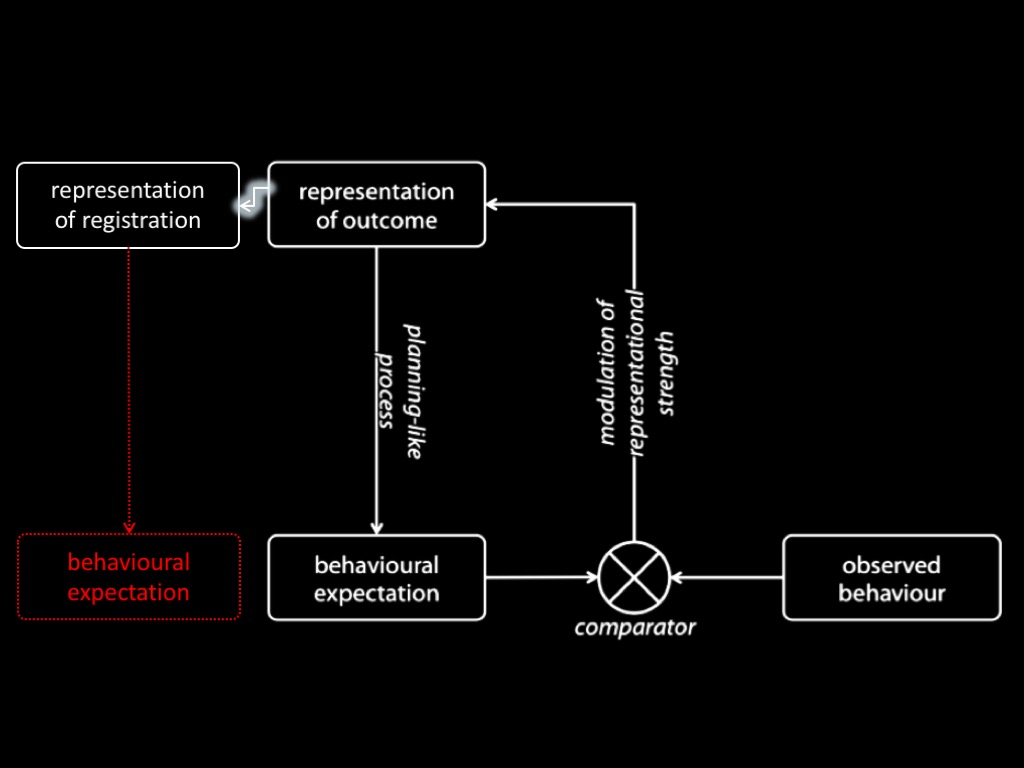

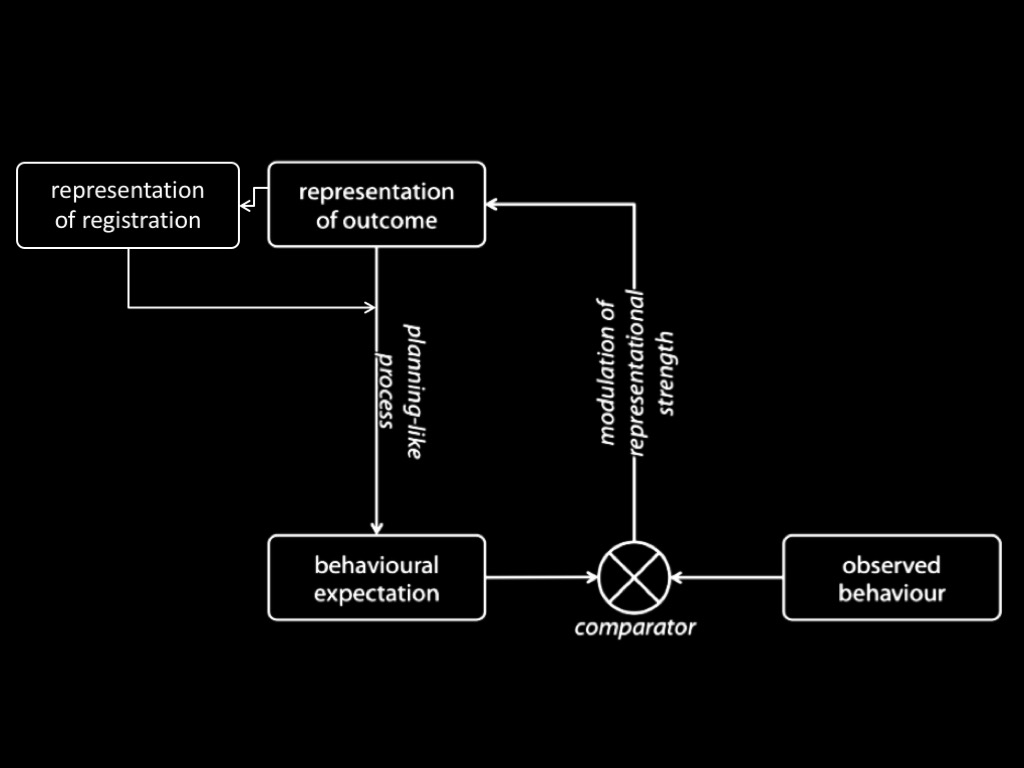

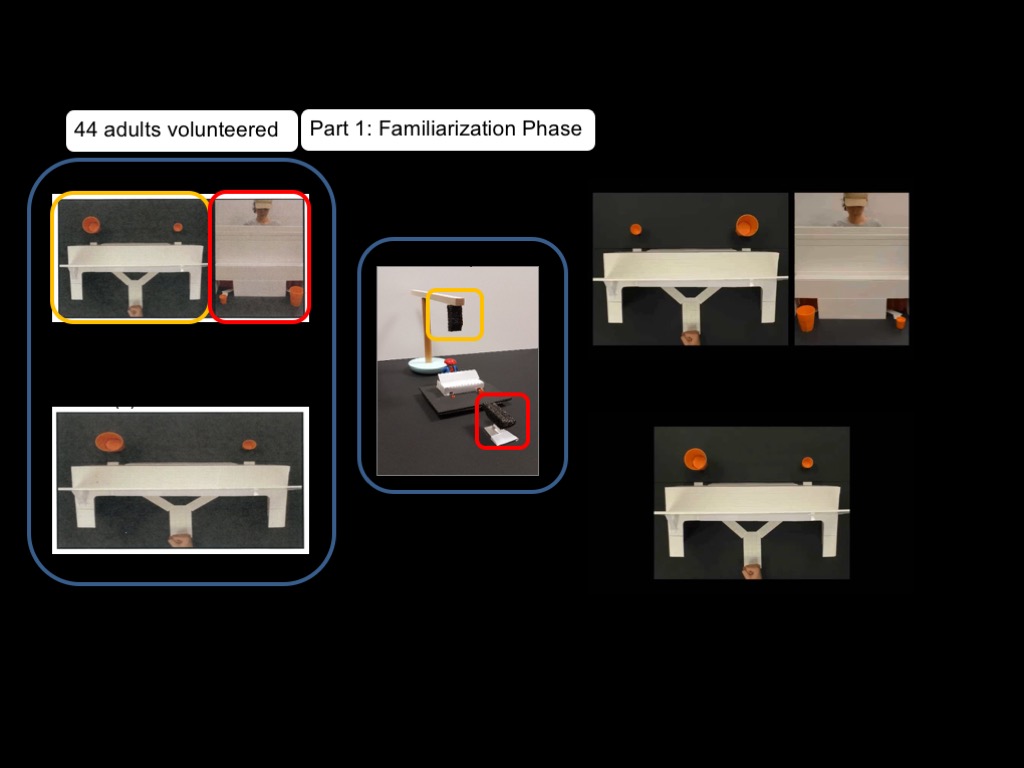

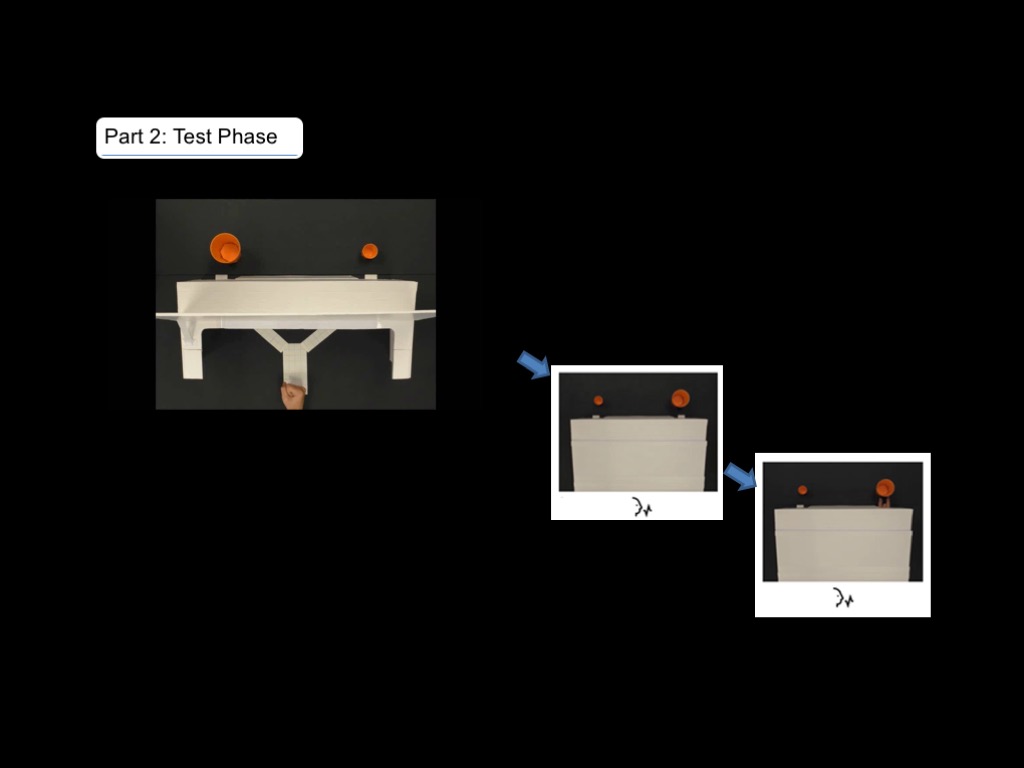

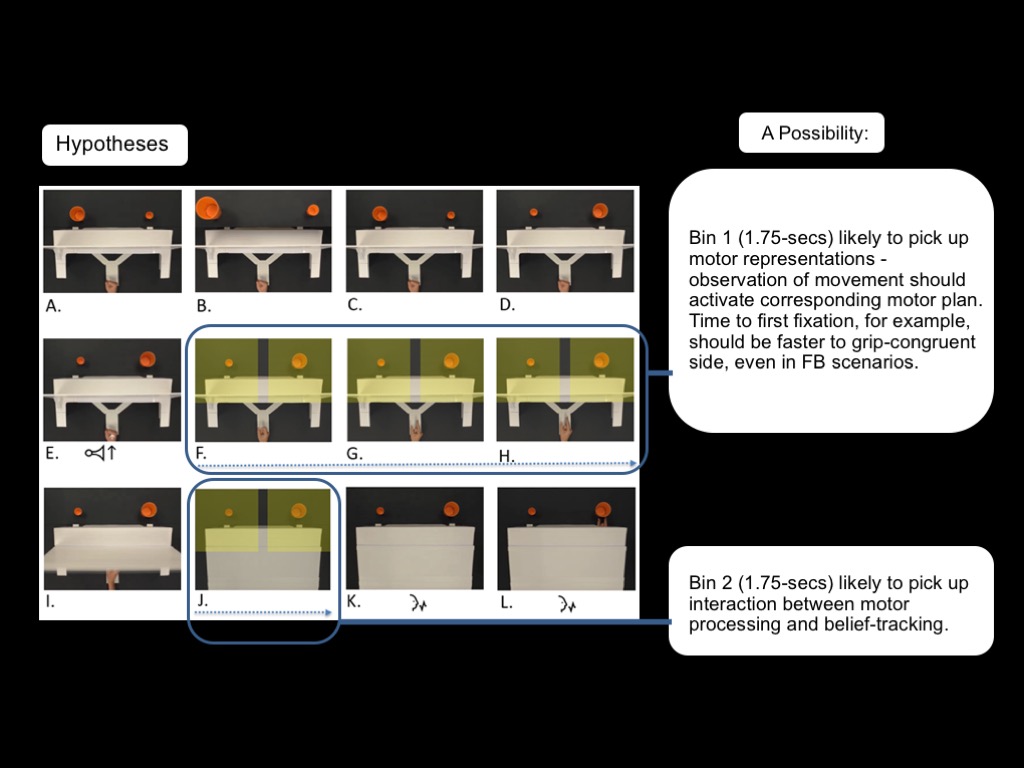

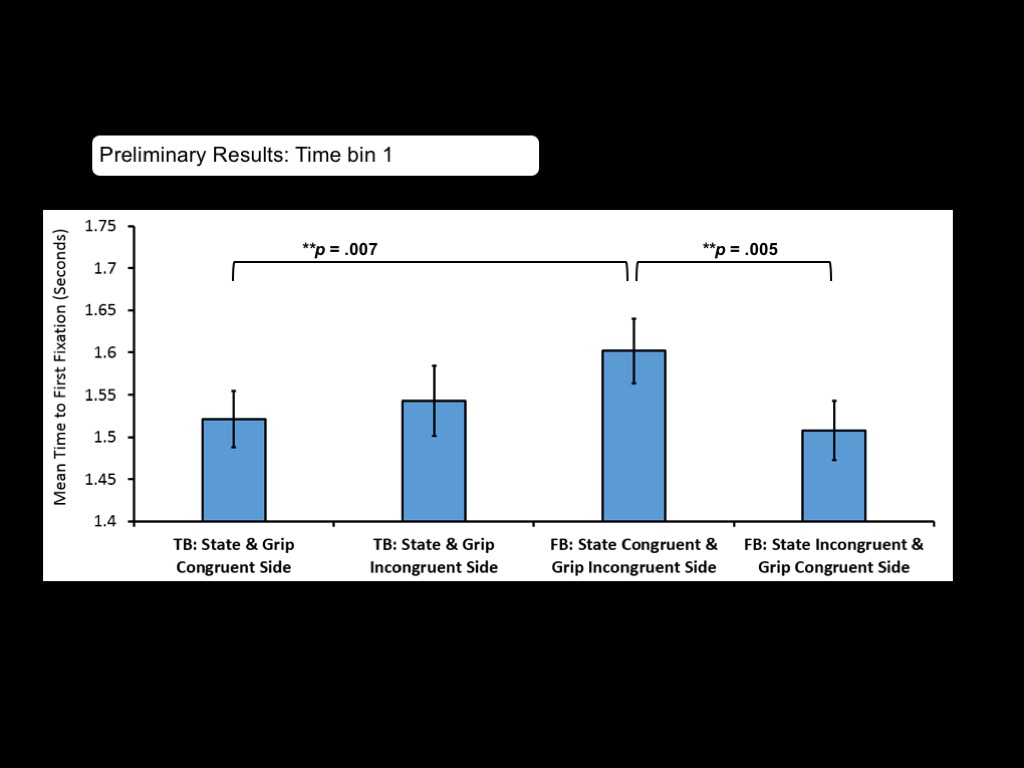

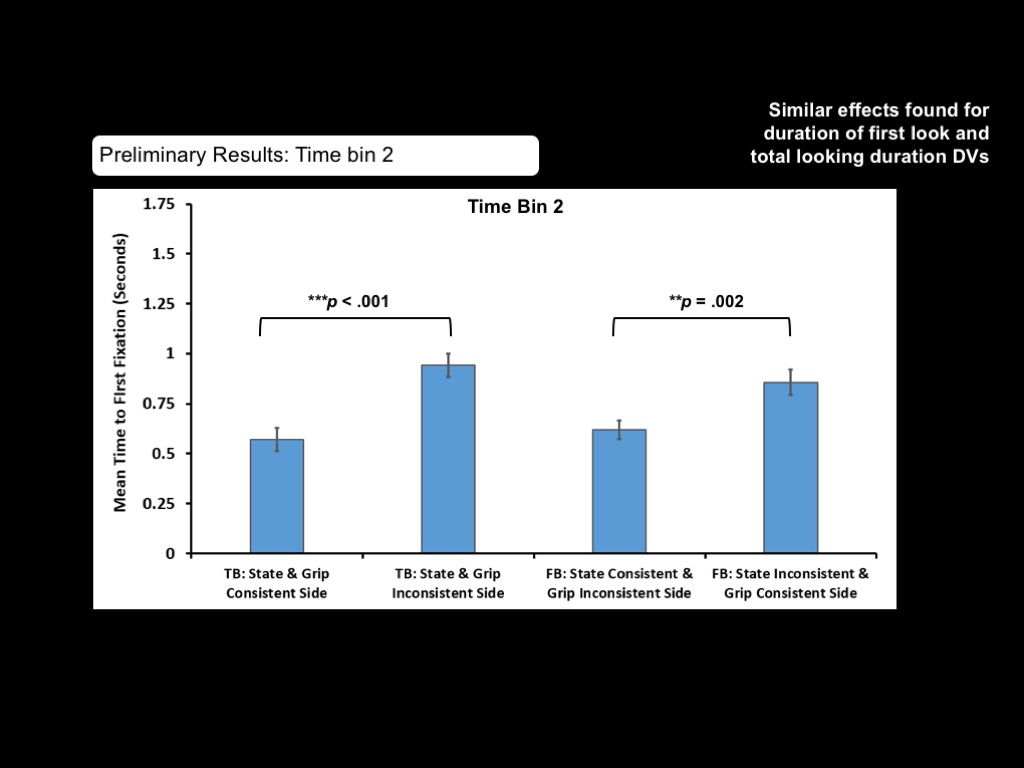

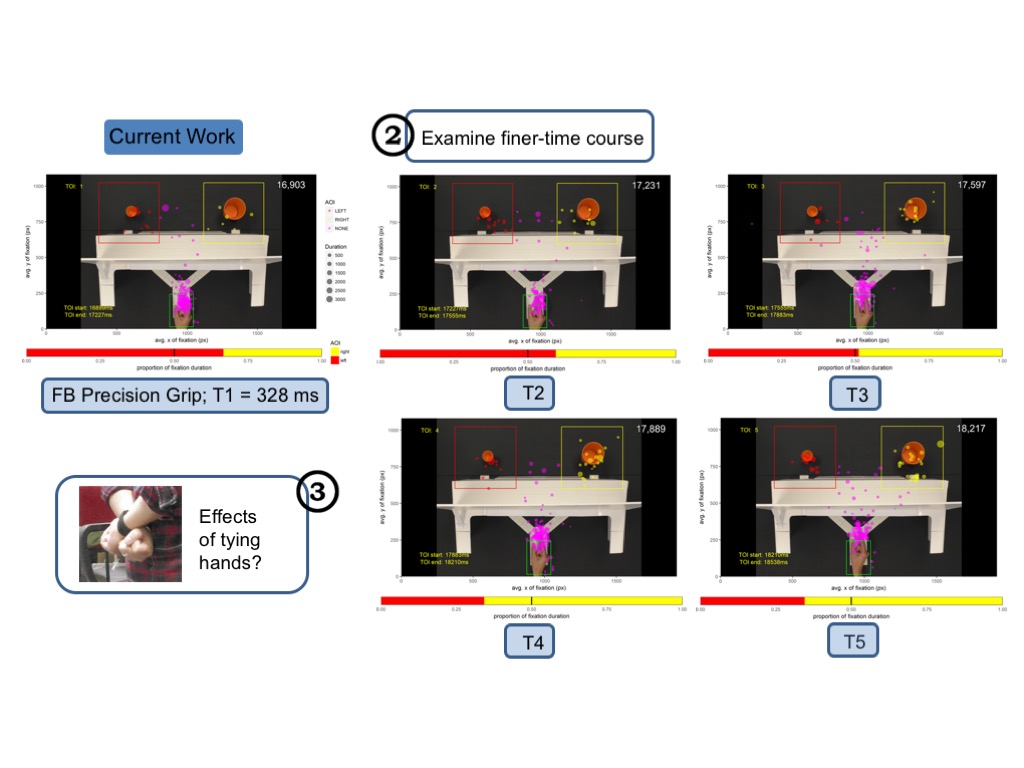

Edwards and Low, 2017 figure 7a

Edwards and Low, 2017 figure 7a

Edwards and Low, 2017 figure 7a

‘There is an early mirror response that is not influenced by the correctness of the movement, and a later modulation that differs according to the correctness of the movements reflecting a deeper level of [cognitive] processing than the early response’

Naish et al., 2014; Neuropsychologia).

conclusion

Is there a role for motor processes in mindreading?

Conjectures:

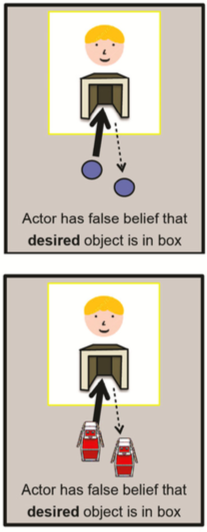

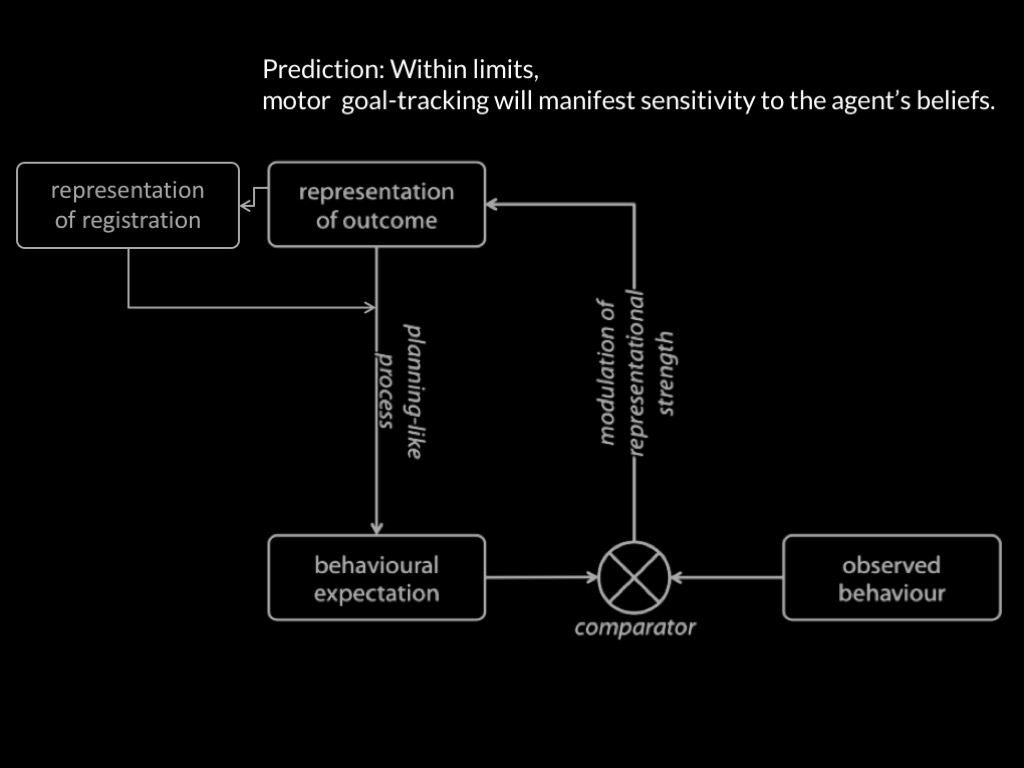

1. Automatic belief-tracking depends on outcomes being represented motorically

2. Automatic belief-tracking can influence motor processes that underpin goal-tracking