Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

14: What Do We Experience of Action?

[email protected]

What can we experience

when we encounter or perform

very small-scale purposive actions?

evidence?

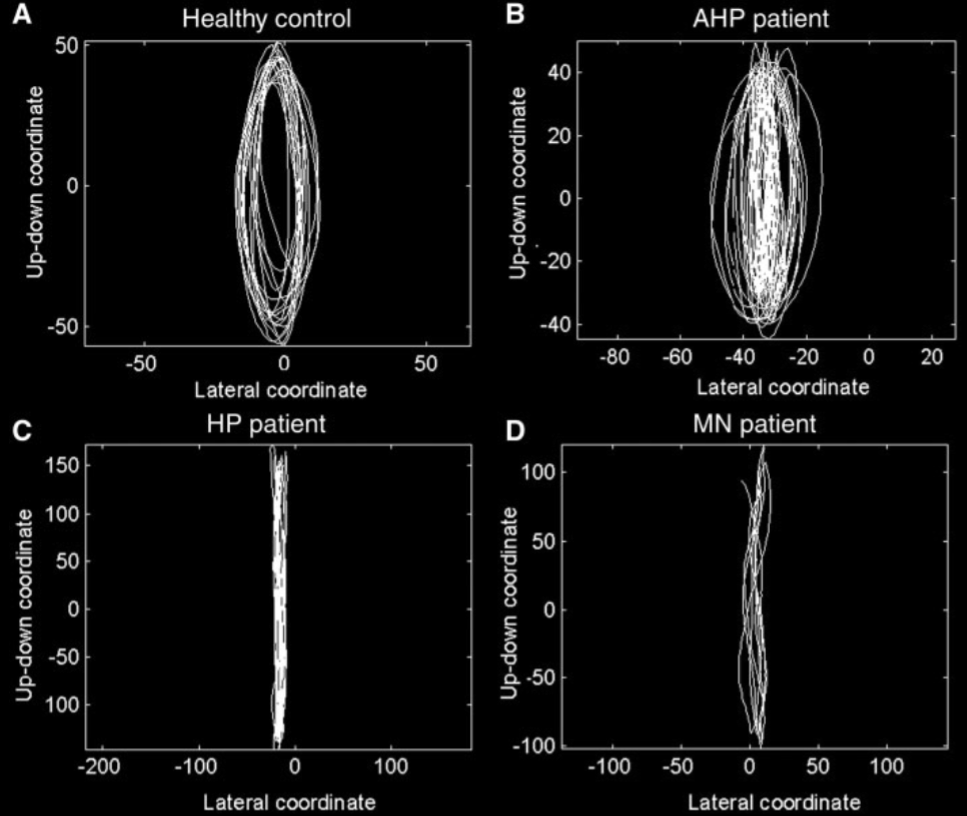

hemiplegia: with vs without anosognosia

Garbarini et al, 2012 figure 3

What can we experience

when we encounter

very small-scale purposive actions?

Experiences revelatory of action

shaped by motor representations.

A Question about Experiences of (Speech) Actions

What do we experience when we

encounter others’ speech actions?

Indirect Hypothesis vs Direct Hypothesis

What do we experience when we

encounter others’ speech actions?

Indirect Hypothesis vs Direct Hypothesis

?

motor representation -> experience of action -> thought

What do we experience when we encounter others’ (speech) actions?

Indirect Hypothesis vs Direct Hypothesis

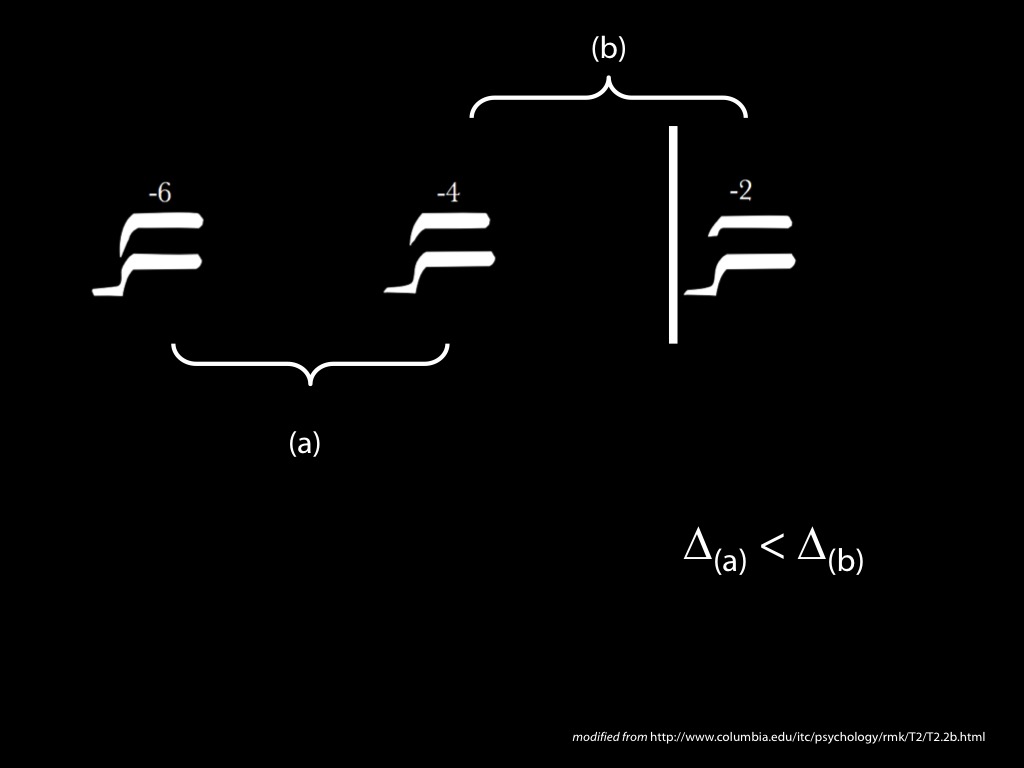

(1) The second sequence of sensory encounters, (b), differ from each other more in phenomenal character than the first sequence of sensory encounters, (a), differ from each other.

(2) This difference in differences in phenomenal character is a fact in need of explanation.

(3) The difference cannot be fully explained by appeal only to perceptual experiences as of acoustic features of the stimuli.

(4) The difference can be explained in terms of perceptual experiences as of phonetic properties.

(5) There is no better explanation of the difference.

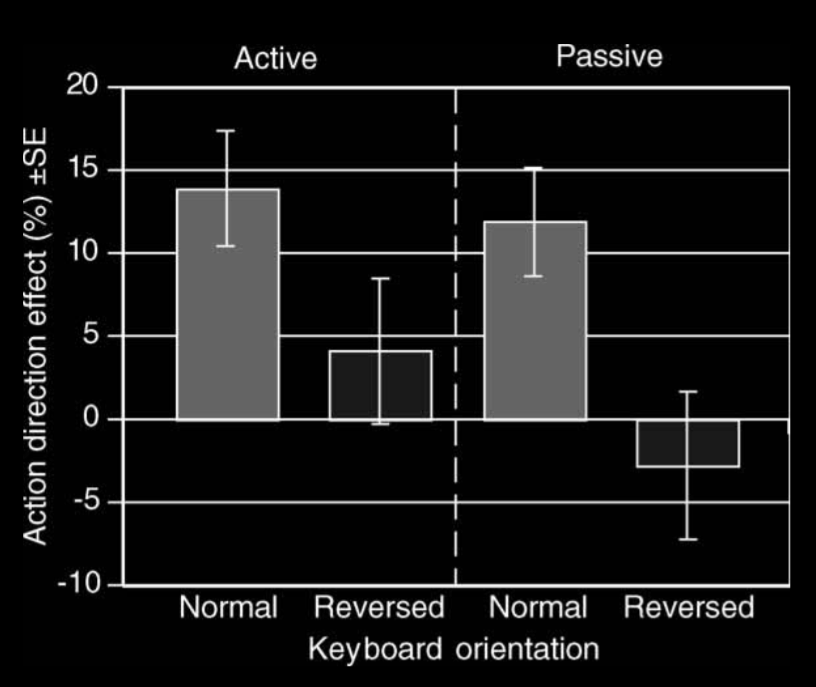

motor processes affect acoustic expeirences

Repp & Knoblich 2009, figure 3

motor processes affect acoustic expeirences

(1) The second sequence of sensory encounters, (b), differ from each other more in phenomenal character than the first sequence of sensory encounters, (a), differ from each other.

(2) This difference in differences in phenomenal character is a fact in need of explanation.

(3) The difference cannot be fully explained by appeal only to perceptual experiences as of acoustic features of the stimuli.

(4) The difference can be explained in terms of perceptual experiences as of phonetic properties.

(5) There is no better explanation of the difference.

What do we experience when we encounter others’ (speech) actions?

Indirect Hypothesis vs Direct Hypothesis

Action Experience

How are non-accidental matches possible?

action

Contents of motor representations vs contents of intentions.

vision

Contents of visual representations vs contents of beliefs.

Visual representations cause visual experiences, which provide reasons for beliefs.

Beliefs (and desires) influence orientation and attention, and thereby visual representations.

model 2: sensations (the feeling of familiarity)

model 3: object indexes

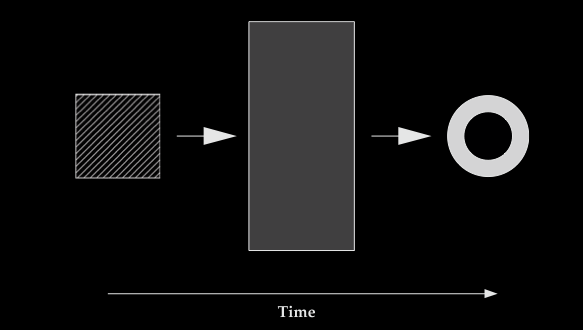

object indexes

Scholl 2007, figure 4

What do object indexes contribute to experience? Structure!

object indexes

belief-independent

structure experiences

subject to limited, indirect cognitive control through attention

motor representations

intention-independent

structure experiences

subject to limited, indirect cognitive control through attention

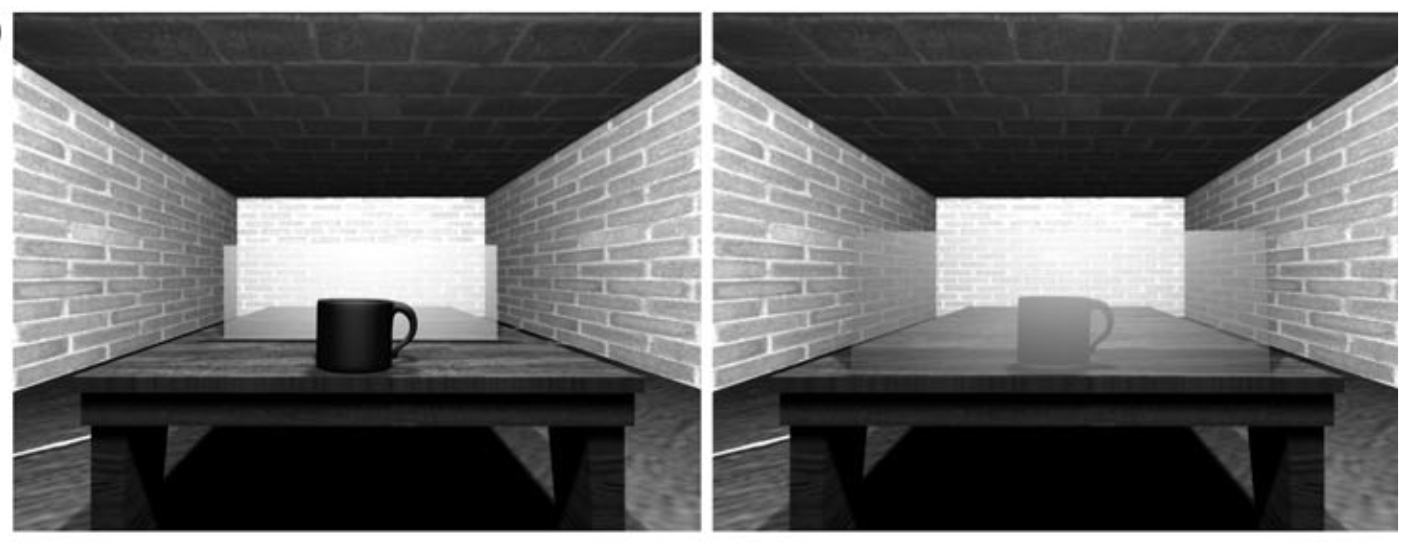

Costantini et al, 2010 figure 1b

‘Action index’ conjecture

Motor representations of outcomes structure

experiences, imaginings and (prospective) memories

in ways which provide opportunities for attention to actions directed to those outcomes.

Forming intentions concerning an outcome can influence attention to the action,

which can influence the persistence of a motor representation of the outcome.

Predictions?

1. Not all action-related changes in experience are merely changes in bodily configurations, movements and their sensory effects.

2. Memory for objects should be influenced by their affordances.