Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

\title {Philosophical Psychology \\ 15: Sharing a Smile}

\maketitle

15: Sharing a Smile

[email protected]

\def \ititle {15: Sharing a Smile}

\begin{center}

{\Large

\textbf{\ititle}

}

\iemail %

\end{center}

\section{Sharing Smiles}

\section{Sharing Smiles}

Sharing smiles and otherwise collectively expressing emotions makes available to us facets of mental states that are not available on the basis of perception.

sharing a smile

So my aim is to show that manifesting collective intentionality enables us to exploit routes to knowledge of others' minds

which would be unavailable if we were entirely passive observers.

To this end I want to focus on a one kind of interaction, sharing a smile.

Preview: I'll argue that sharing a smile provides us with a route to knowledge of facts about the ways others' emotions unfold,

where we might not otherwise be in a position to know these facts.

[FIRST POINT: emotions unfold over time]

When it comes to knowledge of others’ emotions, it might initially seem hard to imagine there could be a role for joint action because mere observation provides so much.

Because there are characteristic expressions of emotion, a mere observer can know of Lily’s amusement just from her facial expression.

Expressions of emotion plausibly also enable us to identify the objects of others’ emotions.

Since the causes of expressions like Lily’s smile are often enough the objects of the emotions they express,

we can identify the objects of emotion using whatever sorts of causal reasoning enable us to work out what someone tripped over.

If you know what is causing Lily to smile you are probably in a position to know what she is amused by, that is the object of her amusement.

Emotions are not simply happiness or fear; they are things that unfold over time.

That initial jolt of fear as you hear the intruder enter your house is becomes intense as she moves closer, and then acquires an angry edge as you hear her breaking that vase your grandmother gave you.

Or imagine watching a clown falling over. Your amusement might develop from an initial wince to growing hilarity that abruptly ends as the clown hits the floor, only to resurge as the wider comic significance of this event becomes apparent.

How could we gain insight into the fine-grained dynamics of others’ emotions?

How could we ever appreciate the unfolding of another’s grief, or the way their engagement leads to an explosion of ecstasy at the climax of a concert?

It's in answering this question that I think we may find support for the idea that collective intentionality enables us to know things about others' emtoions that we might not otherwise be in a position to know.

My thesis will be that Sharing a smile provides us with a route to knowledge of facts about the ways others' emotions unfold; this is what's special, rather than knowledge of the category of emotion (amusement vs fear) or its object.

[SECOND POINT: control is a way of knowing]

ways of knowing: perception, inference, reason, testimony

ways of knowing --- mention perceiving, testimony etc;

agent’s knowledge of their current and future actions is often thought to depend on control (although I guess perception is important---it's not a pure case);

but control can enable us to know things about others’ actions (using reins as an example---the point of putting a toddler in reins is sometimes that they enable you to know where the toddler will be without observation or inference);

\footnote{

Issue (Joel): does control give knowledge of action independently of perception. (I launched into AHP, which I think only ends up supporting the point.) Perception must be relevant in this sense: to know that I’m acting, my judgement must be appropriately sensitive to perceptual confirmation. (Someone with AHP isn’t in a position to know that she’s acting precisely because the perceptual information doesn’t influence her judgement (the comparator---the link between perceptual feedback and motor representation---is broken). (Strictly this doesn’t show that we need perceptual information, just that knowing isn’t compatible with ignoring perceptual information if we have it.) OK, but how does this affect the argument? (i) maybe I shouldn’t offer agential control as a way of knowing that is distinct from perception (although I think that, unlike simple cases of perception, the motor representation plays a role in knowing. Further (ii) what’s perceived is action not emotion in the proposal I make; but then maybe Joel’s objection is that merely controlling isn’t sufficient for knowing---against this, I think the reins example might help (I don’t need perceptual feedback to know the location of the toddler, although I might not be able know the location if I have perceptual feedback and ignore it.)

}

then point out that social interactions often involve reciprocal control.

controlling someone's actions is a way of knowing things about them.

\footnote{

Issue (Tom Smith): is reciprocal control sufficient for joint control? No because of walking in the Tarantino sense. This might tell us something interesting about joint control---e.g. maybe identifying differences between sharing a smile and walking in the Tarantino sense with respect to control will enable me to make the point about control as a way of knowing in sharing a smile better.

}

[THIRD POINT: smiling is a goal-directed action, the goal of which is to smile that smile]

My topic is sharing a smile. But first think about ordinary, individual actions like genuine smiles.

What distinguishes a genuine smile from a muscle spasm or the exhalation of wind?

I want to suggest that it's this: the smile is a goal-directed action where the goal is to simile that smile.

But why think of the smile as goal-directed? Because smiling the smile requires considerable motor coordination: it’s not a matter of simple muscle contractions but more like the production of a phonetic gesture where context affects what is needed to realise the smile.

Further, like grasping an object or articulating a particular phoneme, it is an action that can be realised by different bodily movements in different contexts.

This is why I put slides of two quite different but both genuine smiles.

[Objection:]

Now you might say that the smile can't be goal-directed because is isn't explicable by appeal to belief, desire and intention

This is because the genuine smile is spontaneous and not something that can be produced at will (although it could probably be inhibited, at least to some extent); after all, this is what distinguishes the genuine from the polite smile.

\footnote{

From web source: The Duchenne smile involves both voluntary and involuntary contraction from two muscles: the zygomatic major (raising the corners of the mouth) and the orbicularis oculi (raising the cheeks and producing crow's feet around the eyes). The zygomatic major can be voluntarily contracted but many people can't voluntarily contract the orbicularis oculi muscle.

}

So now we might be tempted by the view that a smile is merely caused by an emotion in the way that gasses can cause you to burp.

[Reply:]

Maybe there are smiles like this, but some genuine smiles are sustained.

And what sustains them is a process of controll

How could this be if such smiles are not consequences of beliefs, desires and intentions?

I think a reasonably natural view here is to think that part of what makes an event a smile, a goal-directed action and not just a muscle spasm caused by excess wind, is the way that motor control is involved. Specifically, the genuine smile will involve a motor representation of the outcome, the smile, and this motor representation will lead to movements by way of planning-like motor processes.

But you don't have to buy this to agree with me.

All you have to accept is that actions like some smilings can be goal-directed and controlled even in the absence of relevant beliefs, desires and intentions.

I think smiles fall into the category of actions like graspings, reachings and gesturings which are goal-directed but do not necessarily involve intention.

So far, then, I've suggested that smiling is a goal-directed action, the goal of which is to smile that smile.

I'm sorry if all of this is too simple to mention, but I want to recap just to be sure we're all together.

summary so far

- emotions unfold over time

- control is a way of knowing

- smiling is sometimes a goal-directed action, the goal of which is to smile a smile

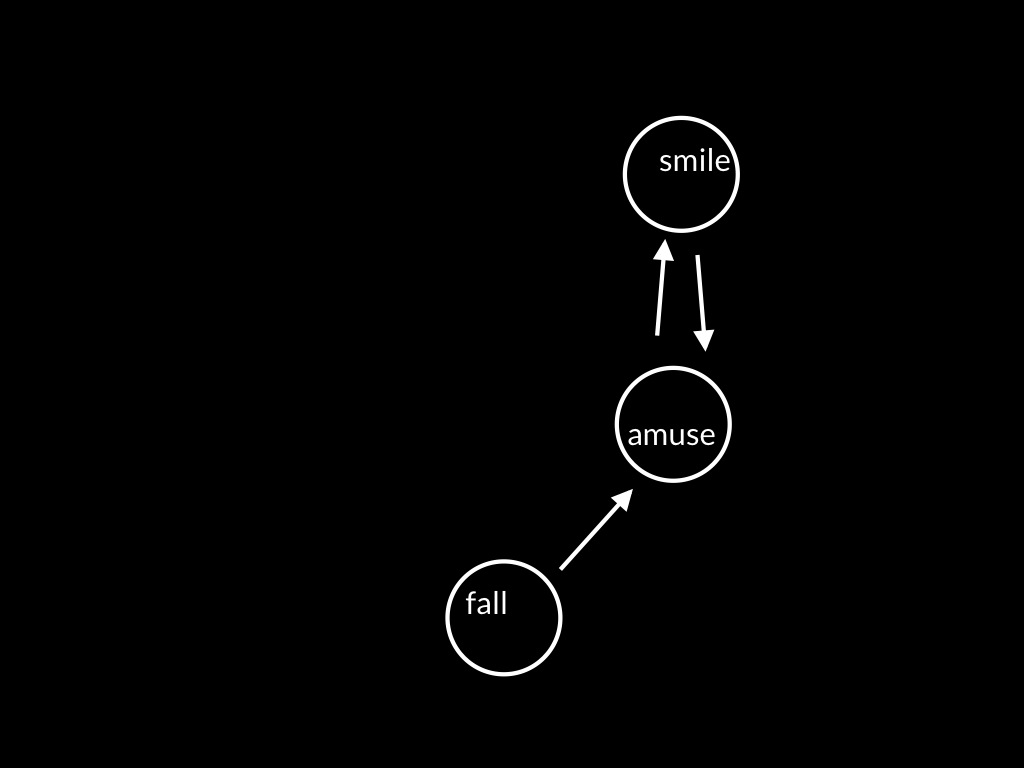

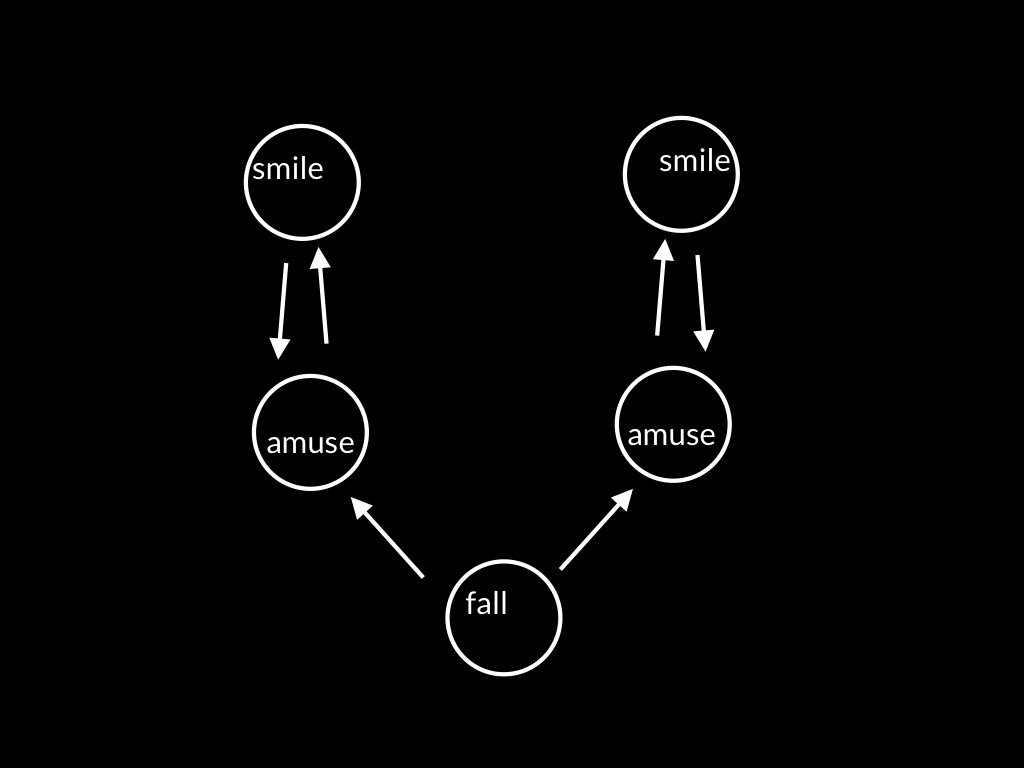

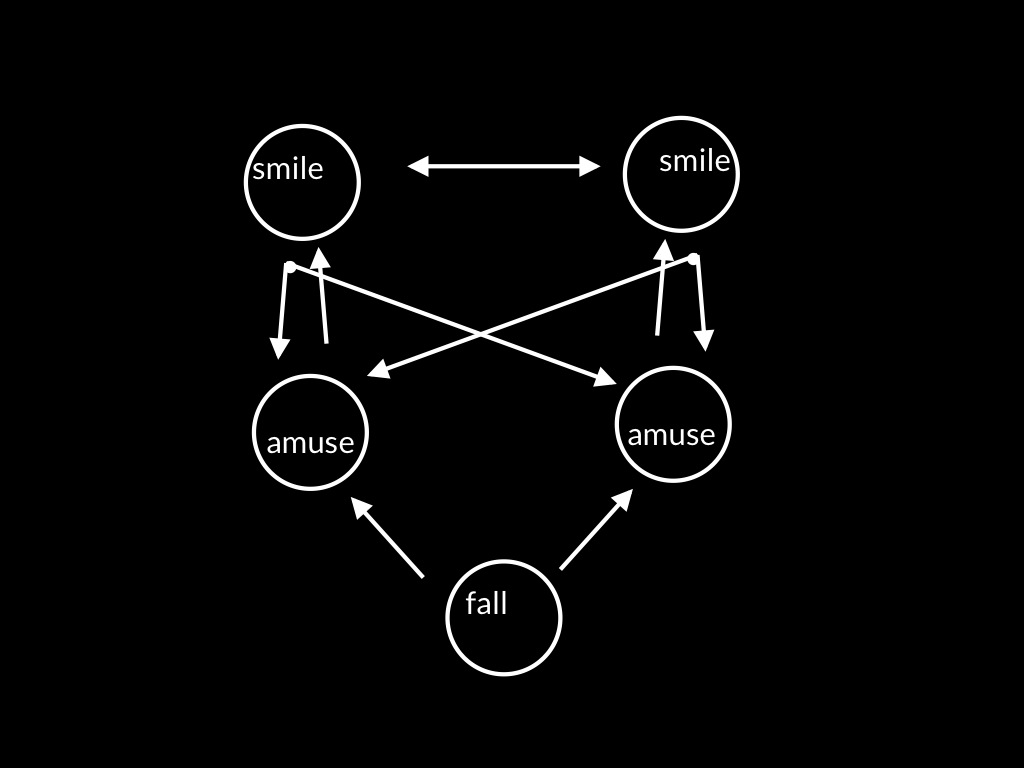

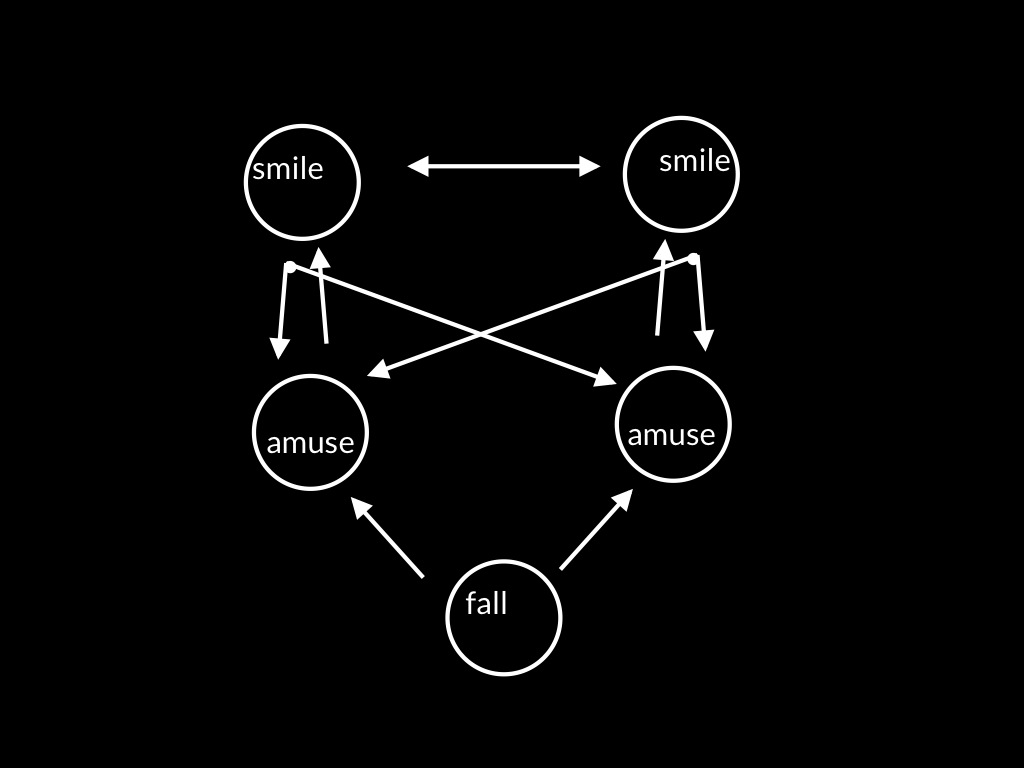

Now imagine a situation where a single individual encounters and event (a clown’s falling) which causes amusement which causes her to smile

Note that the smile also modulates the emotion; if, for example, she supressed the smile, the quality of her amusement would change.

How could we gain insight into the fine-grained dynamics of others’ emotions?

How could we ever appreciate the unfolding of another’s grief, or the way their engagement leads to an explosion of ecstasy at the climax of a concert?

Part of the answer is obvious: by being there, with them.

[Not that this is the only possibility --- in some cases we might be told.]

But how exactly does being there, in the same situation help?

Merely being in the same situation is surely not enough.

It’s not enough that we each experience amusement, grief or ecstasy.

After all, individuals are different. Different individuals’ feelings don’t unfold in the same way just because they are in the same situation.

It’s just here that collective intentionality is relevant.

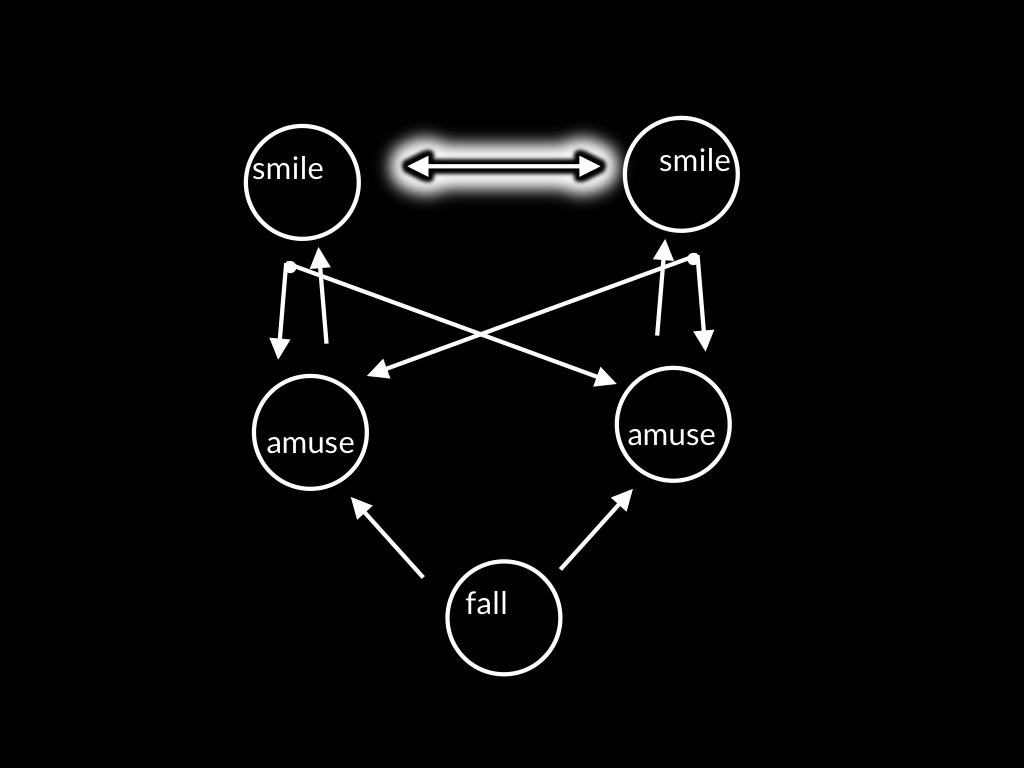

\textbf{What is involved in sharing a smile?}

Minimally, I think there have to be two kinds of connection between us for us to share a smile.

First, the way your smile unfolds is shaped by how mine unfolds and conversely.

I also suppose that our smiles can be minutely coordinated with each other.

But it’s not just that our smiles are interdependent in this way ...

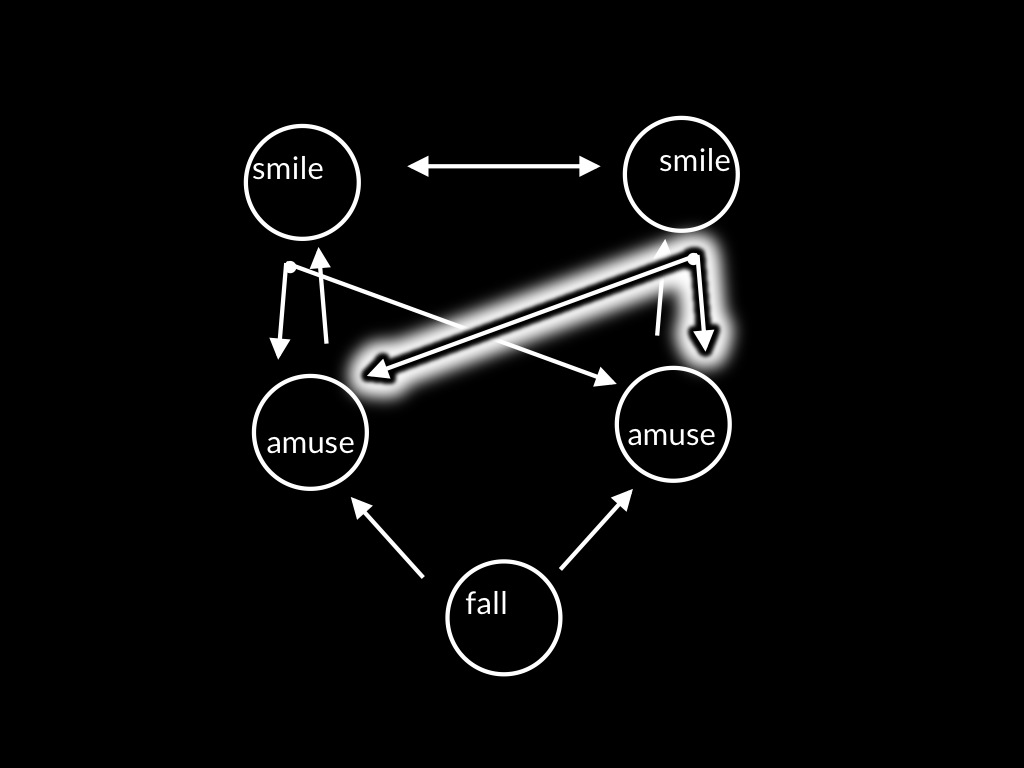

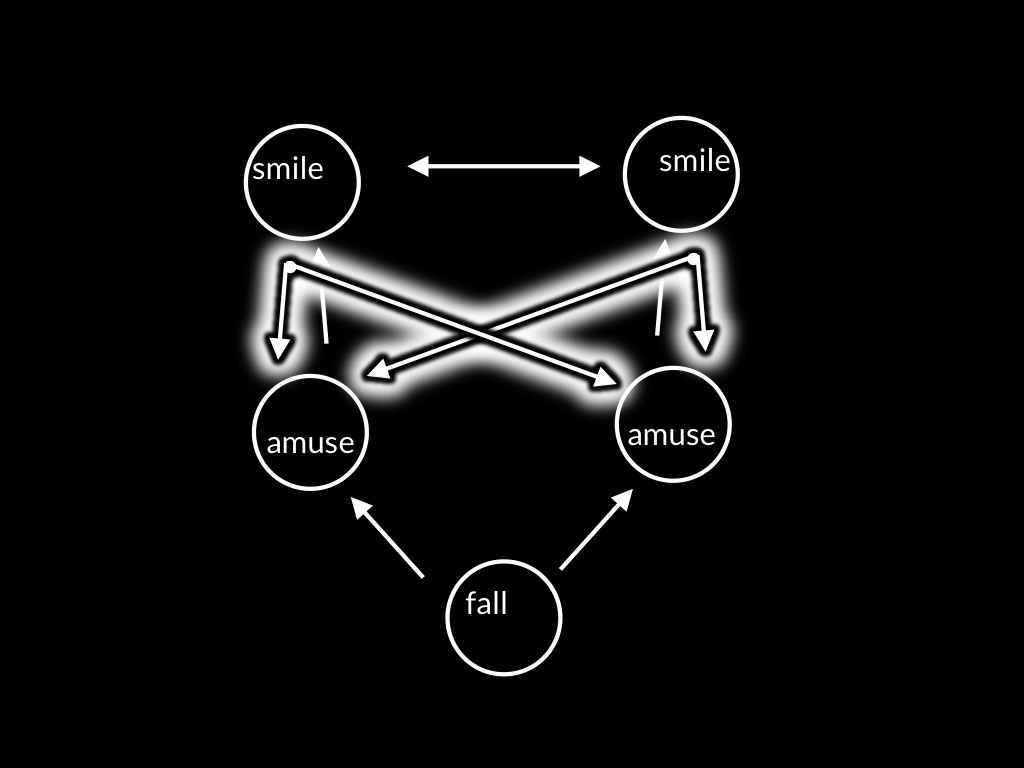

It’s also that each of our smiles is shaping the way our amusement unfolds.

So the way your amusement unfolds is being controlled by, and controlling, the way mine unfolds.

In sharing a smile, we are emotionally locked together.

[*todo: remove motor stuff for this talk! Also: don't lose sight of idea that control is a way of knowing.]

[*todo: need slide with control arrows highlighted (my emotion controls yours).]

[*Structure:

(i) I know because my emotion controls yours;

(ii) But if my emotion controls yours, how can yours be amusement at the clown's falling? because control is partial, and reciprocal;

(iii) But the mere fact of control isn't enough for knowledge; rather, control must show up in experience somehow.

After all, for all I have said so far, we might, in sharing a smile, be unaware that our emotions are locked together.

(iv) There must be an experience that is distinctive of sharing a smile.

(iv) Note that I don’t want to say that someone who is sharing a smile needs to understand the situation in the way I’m describing it.

All I'm claiming is that the fact of reciprocal control somehow affects our awareness.

(v) It may affect in our awareness insofar as we are sensitive to contingencies between our own actions' and others' actions,

and between our actions and the causes of them.

(vi) So my position is this: the reciprocal control justifies each agent in making judgements about how the others' amusement is unfolding,

and this justification is at least indirectly available to the agents by virtue of their having experiences characteristic of sharing a smile.

]

Our being emotionally locked together means that

to a significant extent I am feeling what you are feeling,

that the way my amusement is unfolding matches they way your amusement is unfolding.

So if you know how your own amusement is unfolding and you know that we are emotionally locked together,

you can know much about how my amusement is unfolding.

So joint expressions of emotion like sharing a smile have the potential to enable us to know not just that others are amused but how their amusement is unfolding.

But the fact of reciprocal control (which means our emotions are locked together) together doesn’t all by itself mean that we can know how each other’s emotions are unfolding.

After all, for all I have said so far, we might, in sharing a smile, be unaware that our emotions are locked together.

Now you might think this sounds implausible because its hard to imagine sharing a smile without an experience that is distinctive of sharing a smile.

And it might be natural to describe this experience as an experience of sharing.

But even if that is correct, it’s necessary to say exactly why someone who is sharing a smile is in a position to know things about how the other’s emotion is unfolding.

I don’t want to say that interaction only helps if you know that your emotions are locked together.

That is, I don’t want to say that someone who is sharing a smile needs to understand the situation in the way I’m describing it.

But minimally the fact of reciprocal control must somehow feature in our awareness.

[*The idea in outline:

\begin{enumerate}

\item the ways our amusements unfold is locked together

\item this is in part because a single motor plan has two functions, production of your smile and prediction of my smile

\item the single motor process means that we might experience being locked together in some way (not that our emotions are locked together but that our actions are, in something like (but not exactly) we experience actions when seeing ourselves in a mirror or on CCTV (check Johannes’ discussion of this)).

\end{enumerate}

]

Here I want to offer a wild conjecture.

In joint expressions of emotion there is a single motor plan with two functions,

production and prediction.

The motor plan both produces your own smile and enables you to predict the way the other’s smile will unfold.

[*missing step about monitoring and experience. (The Haggard idea: motor planning can give rise to experiences concerning one's own actions \citep{Haggard:2005sc}.)]

Because your plan has this dual function, your experience of the other’s (my?) smile is special.

From your point of view, it is almost as if the other is smiling your smile.%

\footnote{

Joel caricatured this idea seeing me eating fruit: ‘it’s almost as if I’m eating that fruit.’

}

This means that sharing a smile has characteristic phenomenology.

This odd phenomenological effect means that in sharing a smile we can each think of the situation almost as if there were a single smile.

And almost as if there were a single state of amusement.

(In thinking of the situation like this it is important that we have a subject-neutral conception of the amusement and an agent-neutral conception of the smile.%

\footnote{

Tom Smith asked about this. I clarified that I wasn’t suggesting there was a state of amusement which is ours, nor that the subjects are thinking of the situation in this way.

That’s the point of the appeal to subject-neutral amusement.

It’s a partial model of the situation.

}

[*Here I think I’m shifting back from the perspective of the participants in sharing a smile to the perspective of the theorist.

Probably what I should say is, first, that a theorist can think of the situation in this way and use this to argue, second, that there is a simple, partial conception of the situation that doesn’t require understanding reciprocal control and interlocking emotions but is sufficient for each smiler to have knowledge of the way the other’s emotion unfolds.]

So my suggestion is that in sharing a smile you experience my smile almost as if it were yours (or: you experience me almost as if I were smiling your smile),

and so you might also experience our situation almost as if it involved a single state of amusement.

It's more like we each plan a single smile.

But---to reply to the objection---these plans have a dual function.

Your plan both produces your own smile and enables you to simulate---to experience---my smile.

And likewise for my plan.

The interdependence of our smilings means that we could each think of the situation as if it were one in which a single state of amusement were responsible for our actions.

collective intentionality opens a route to knowing others’ minds

I've just been arguing that manifestations of collective intentionality enable us to know things about others' minds that we might not otherwise be in a position to know.

In particular, I suggested that

sharing a smile provides us with a route to knowledge of facts about the ways others' emotions unfold.

\textbf{

Engaging in collective actions like sharing a smile (and crying together) enables us to understand others’ emotions in ways that we probably couldn’t understand them if we were mere observers and unable to engage in collective action.

The joint expression of emotion matters because it makes available a perspective from which it is almost as if your amusement is my amusement, and my grief is yours.

}