Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

16: Should You Be Instrumentally Rational?

[email protected]

What is rationality?

preferences

To exhibit instrumental rationality is to select those actions which you expect to best satisfy your preferences.

‘the laws of decision theory (or any other theory of rationality) are not empirical generalisations about all agents. What they do is define what is meant ... by being rational’

Davidson, 1987 p. 43

‘the revealed preference revolution of the 1930s (Samuelson, 1938)

... replaced the supposition that people are attempting to optimize any externally given criterion (e.g., some psychologically interpretable motion of utility, perhaps to be quantified in units of pleasure and pain).

Rather, if economic agents are typically assumed to be subject to relatively mild consistency conditions (e.g., such as transitivity ...), it can be shown that there will exist a set of probabilities and utilities such that each agent’s choices will be just “as if” that agent were maximizing expected utility’

Chater, 2014

‘Suppose that A and B are [outcomes] between which the agent is not indifferent, and that N is an ethically neutral condition [i.e. the agent is indifferent between N and not N].

Then N has probability 1/2 if and only if the agent is indifferent between the following two gambles.

B if N, A if not

A if N, B if not'

Jeffrey, 1983 p. 47

‘As ordinarily understood, the prescription to maximize your expected utility presupposes that there is some measure of expected utility that applies to you and that your preferences are therefore obliged to maximize.

But in the context of decision theory, the utility and probability functions that apply to you are constructed out of your preferences, and so your expected utility is not an independent measure that your preferences can be obliged to maximize;

rather, your expected utility is whatever your preferences do maximize, if they obey the axioms.

Hence, the injunction to maximize your expected utility can at most mean that you should have preferences that can be represented as maximizing some measure (or measures) of expected utility, which will then apply to you by virtue of being maximized by your preferences’

Velleman, 2000 p. 149

motivational states

primary motivational states

not directly modifiable by learning

- hunger

- thirst

- lust

- disgust

- ...

preferences

changing, influenced by learning (and fashion, ...)

- chocolate over rhubarb

- lime over lemon

- red over blue

- ...

Can your primary motivational states diverge from your preferences?

Devaluation - standard procedure:

Training: Rat is put in chamber with Lever; pressing Lever dispenses sucrose (novel food).

Devaluation: Rat is taken into another chamber, poisoned, and then exposed to sucrose.

Extinction Test: Rat returns to chamber with Lever; pressing Lever does nothing.

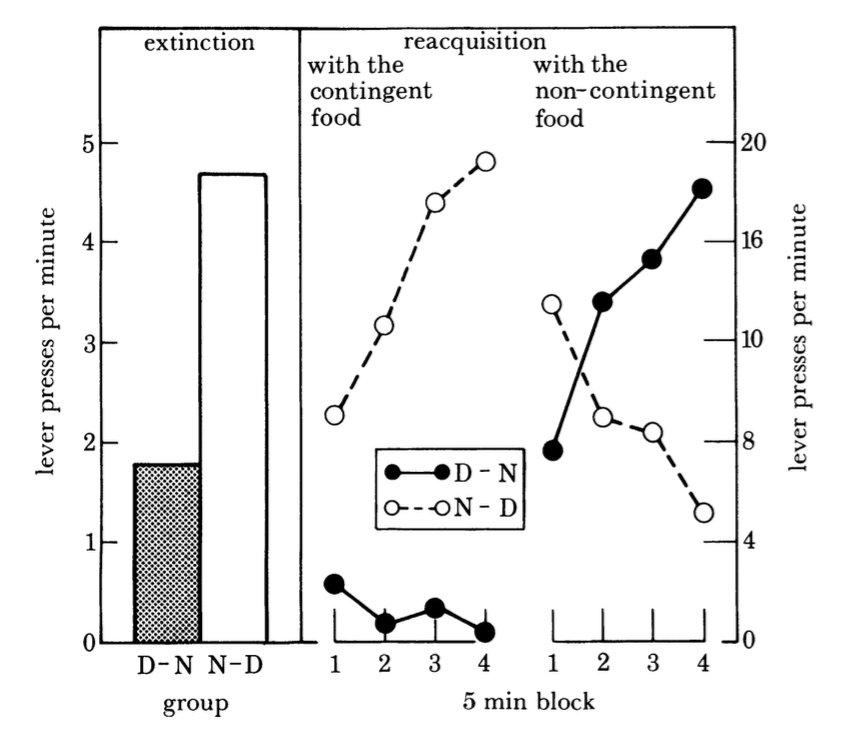

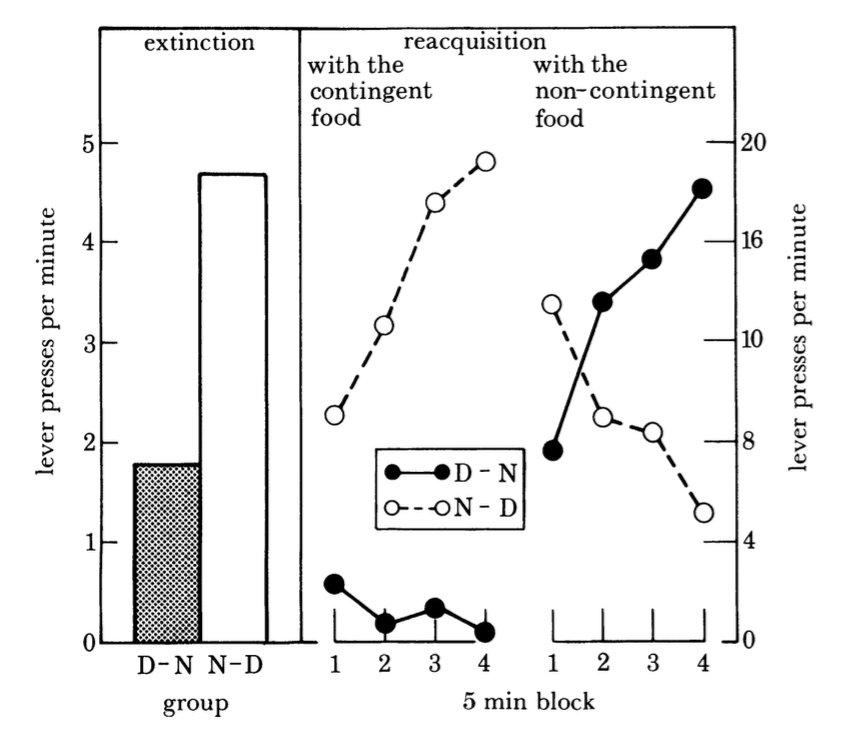

Dickinson, 1985 figure 3; Balleine & Dickinson, 1991 figure 1 (part)

‘The dissociation between lever pressing and magazine entries produced by re-exposure is [...] problematic for the incentive learning account.

To recapitulate, this explanation assumes that instrumental performance is mediated by some “representation” of the relationship between the instrumental action and reinforcer that also encodes the current incentive value of the reinforcer. The represented incentive value can only be changed, however, after aversion conditioning by exposure to the reinforcer.

Given this account, the question immediately arises as to why re-exposure is necessary for a change in lever pressing but not magazine entries’

Balleine & Dickinson, 1991 p. 293

Why do

the two actions,

lever pressing

and

magazine entry,

dissociate in this way?

conditioning

Pavlovian (classical)

Results in stimulus-stimulus links (e.g. bell-food)

The animal responds to the first stimulus as if the second were present

Acquired through exposure to contingencies

Subject to overshadowing and blocking (u.a.)

Operant

Results in stimulus-action links

The animal responds to the stimulus by performing the action

Acquired through being rewarded when acting in the presence of the stimulus

Involved habitual processes

habitual

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Agent is rewarded [/punished]

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened [/weakened] due to reward [/punishment]

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

instrumental

Action leads to Outcome.

Action-Outcome Link is strengthened.

Agent has strong [/weak] positive [/negative] Preference for Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the strength of Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Preference.

conditioning

Pavlovian (classical)

Results in stimulus-stimulus links (e.g. bell-food)

The animal responds to the first stimulus as if the second were present

Acquired through exposure to contingencies

Subject to overshadowing and blocking (u.a.)

Operant

Results in stimulus-action links

The animal responds to the stimulus by performing the action

Acquired through being rewarded when acting in the presence of the stimulus

Involved habitual processes

Why do

the two actions,

lever pressing

and

magazine entry,

dissociate in this way?

Because

magazine entry but not lever pressing ‘is under the control of Pavlovian ... contingencies’

and Pavlovian contingenies enable primary motivational states directly influence action.

Balleine & Dickinson, 1991 p. 294

Devaluation - standard procedure:

Training: Rat is put in chamber with Lever; pressing Lever dispenses sucrose (novel food).

Devaluation: Rat is taken into another chamber, poisoned, and then exposed to sucrose.

Extinction Test: Rat returns to chamber with Lever; pressing Lever does nothing.

Dickinson, 1985 figure 3; Balleine & Dickinson, 1991 figure 1 (part)

Aversion does not directly influence preferences.

‘The pattern of results accords [...] with a role for an incentive learning process in the reinforcer devaluation effect;

not only must consumption of the reinforcer be paired with toxicosis,

the animals must also have an opportunity to contact the reinforcer after aversion conditioning if there is to be a change in instrumental performance’

Balleine & Dickinson, 1991 p. 293

Can your primary motivational states dissociate from your preferences?

motivational states

primary motivational states

not directly modifiable by learning

- hunger

- thirst

- satiety

- disgust

- ...

preferences

changing, influenced by learning (and fashion, ...)

- chocolate over rhubarb

- lime over lemon

- red over blue

- ...

What kinds of processes in

individual animals

guide actions?

Two conclusions:

1. two kinds of process -- habitual vs instrumental

2. two kinds of motivational state -- primary vs preferences

‘the laws of decision theory (or any other theory of rationality) are not empirical generalisations about all agents. What they do is define what is meant ... by being rational’

Davidson, 1987 p. 43

dilemma

Prioritise one kind of motivational state over all others.

Assume that despite multiple kinds of motivational state at the level of representations and algorithms, the system as a whole will satisfy the axioms governing preferences (e.g. transitivity).

‘As ordinarily understood, the prescription to maximize your expected utility presupposes that there is some measure of expected utility that applies to you and that your preferences are therefore obliged to maximize.

But in the context of decision theory, the utility and probability functions that apply to you are constructed out of your preferences, and so your expected utility is not an independent measure that your preferences can be obliged to maximize;

rather, your expected utility is whatever your preferences do maximize, if they obey the axioms.

Hence, the injunction to maximize your expected utility can at most mean that you should have preferences that can be represented as maximizing some measure (or measures) of expected utility, which will then apply to you by virtue of being maximized by your preferences’

Velleman, 2000 p. 149

dilemma

Prioritise one kind of motivational state over all others.

Assume that despite multiple kinds of motivational state at the level of representations and algorithms, the system as a whole will satisfy the axioms governing preferences (e.g. transitivity).

Should we try to resolve or escape the dilemma?

Game Theory

Aim: describe rational behaviour in social interactions.

An action is rational

in a noncooperative game

if it is a member of a nash equilibrium?

Entails:

Resisting (‘cooperating’) is not rational in the Prisoner’s Dilemma.

Choosing ‘Low’ in Hi-Low is rational.

‘The problem with measuring risk preferences is not that measurement is difficult and inaccurate; it is that there are no risk preferences to measure – there is simply no answer to how, ‘deep down’, we wish to balance risk and reward.

And, while we’re at it, the same goes for the way people trade off present against future; how altruistic we are and to whom; how far we display prejudice on gender, race, and so on...

... there can be no method...that can conceivably answer this question, not because our mental motives, desires and preferences are impenetrable, but because they don‘t exist’

Chater 2008, p. 123--4

On explanation: ‘Many events and outcomes prompt us to ask: Why did that happen? [...] For example, cutthroat competition in business is the result of the rivals being trapped in a prisoners’ dilemma’

Dixit et al, 2014 p. 36