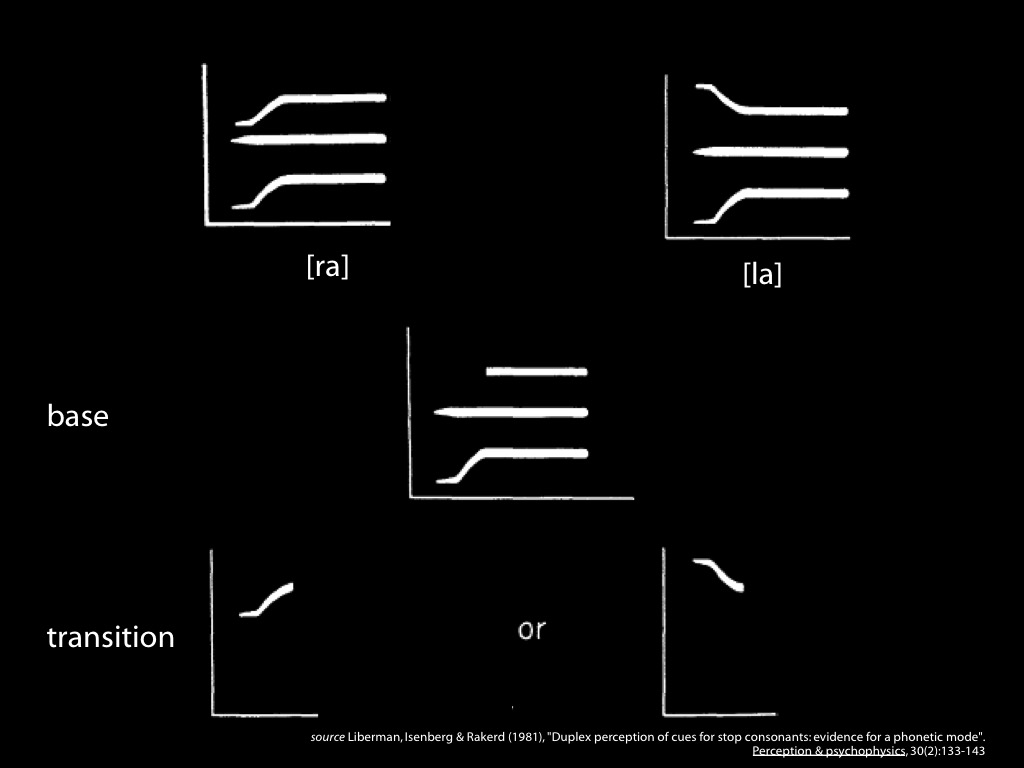

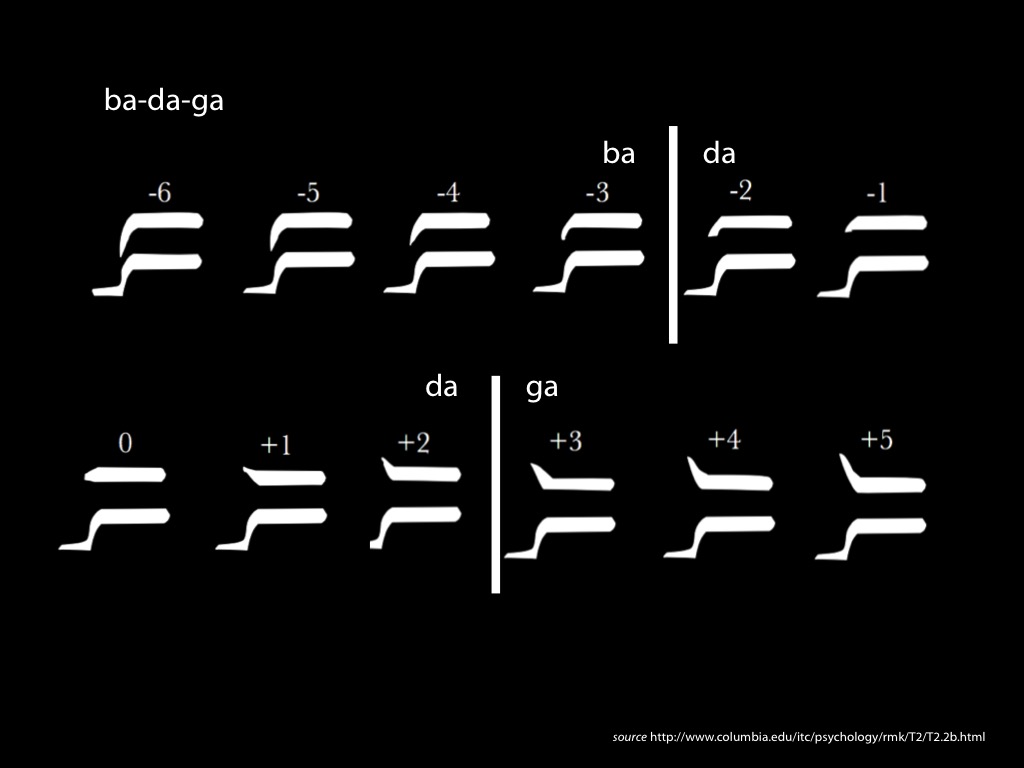

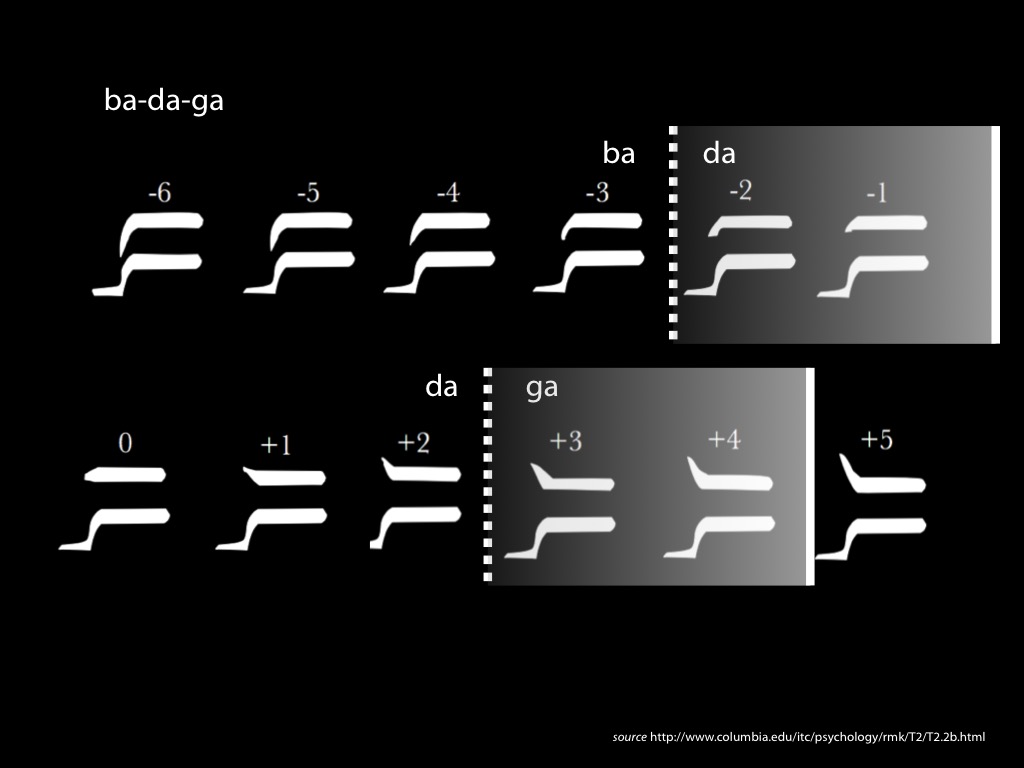

In the middle you see the \emph{base}, i.e. the part of the spectrogram common to [ra] and [la]. This

is played to one ear

Below you see the transitions, , i.e. the parts of the spectrogram that differ between [ra] and [la].

When played in isolation these sound like a chirp. When played at the same time as the base but in

the other ear, subjects hear a chirp and a [ra] or a [la] depending on which transition is played.

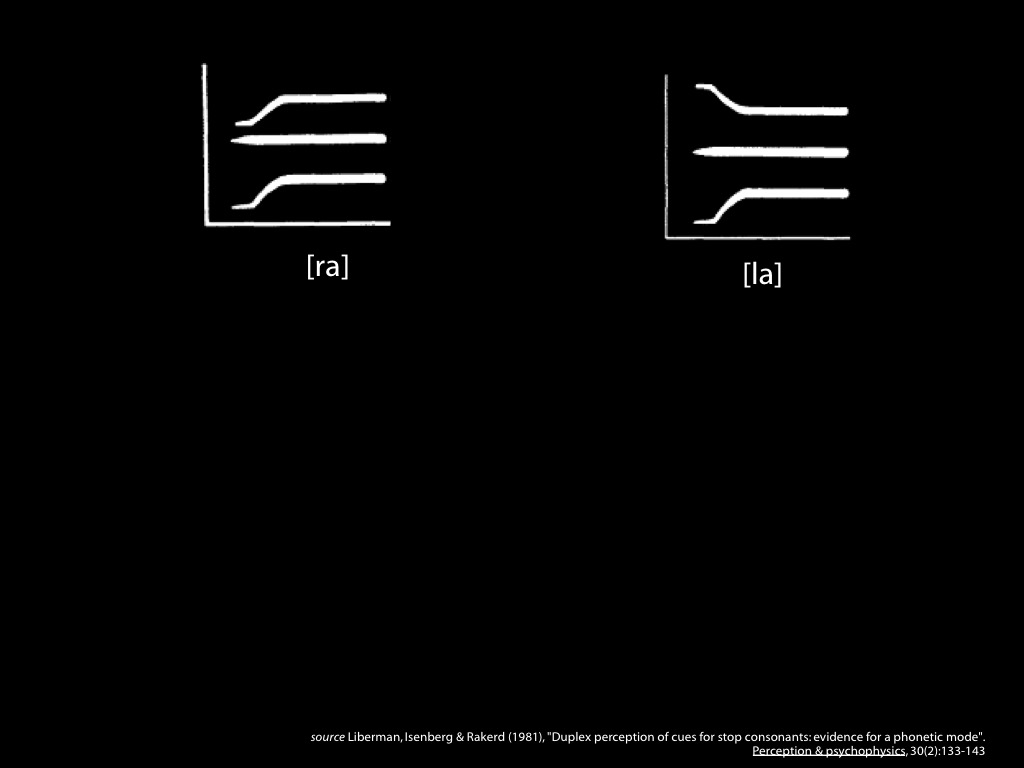

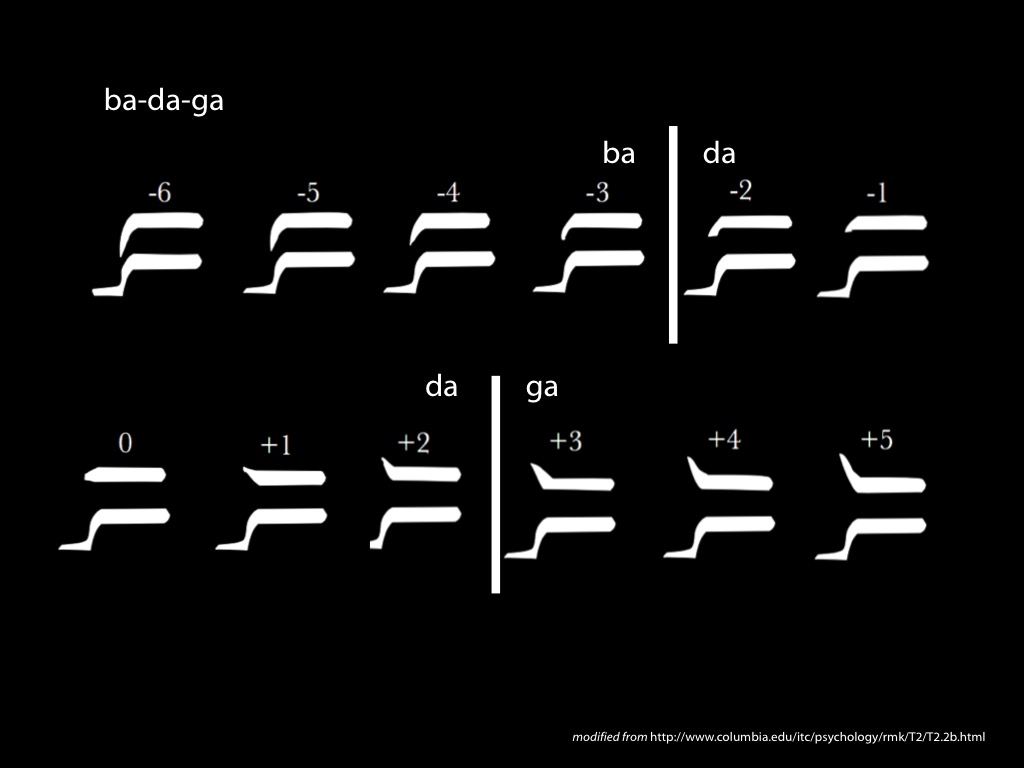

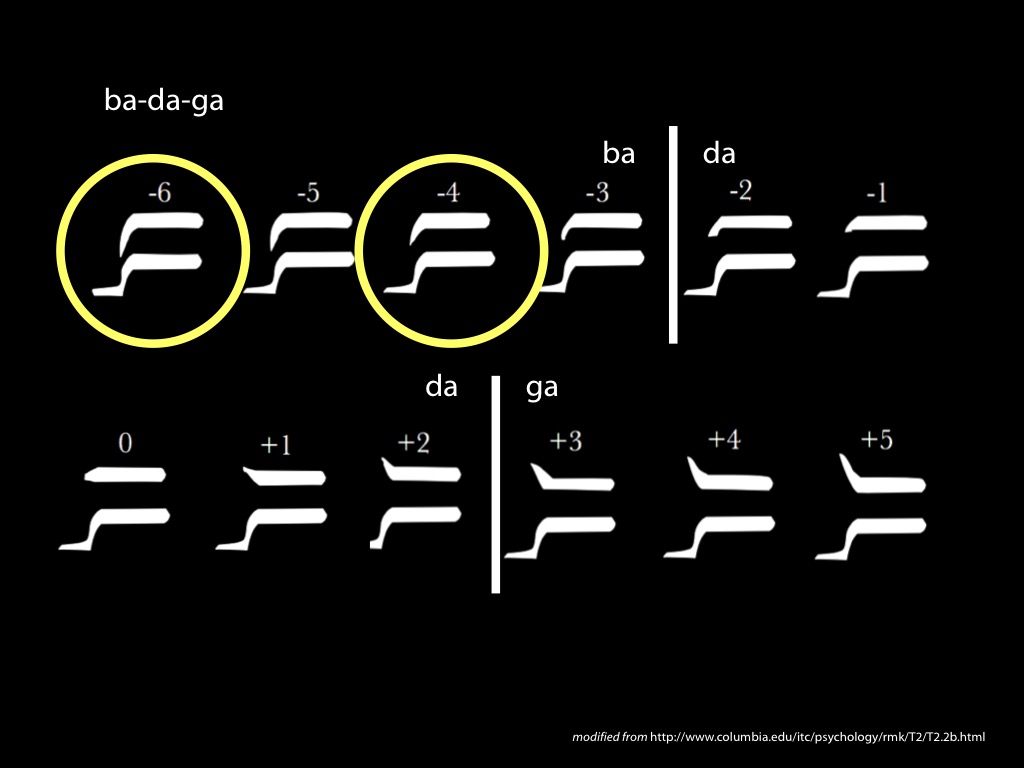

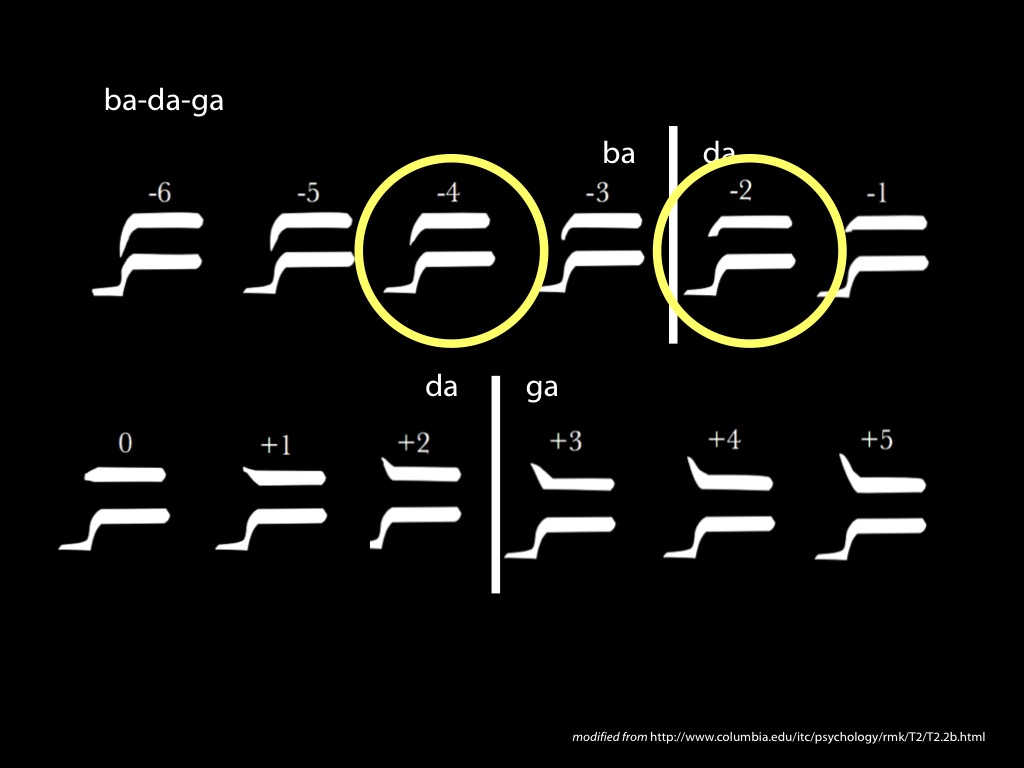

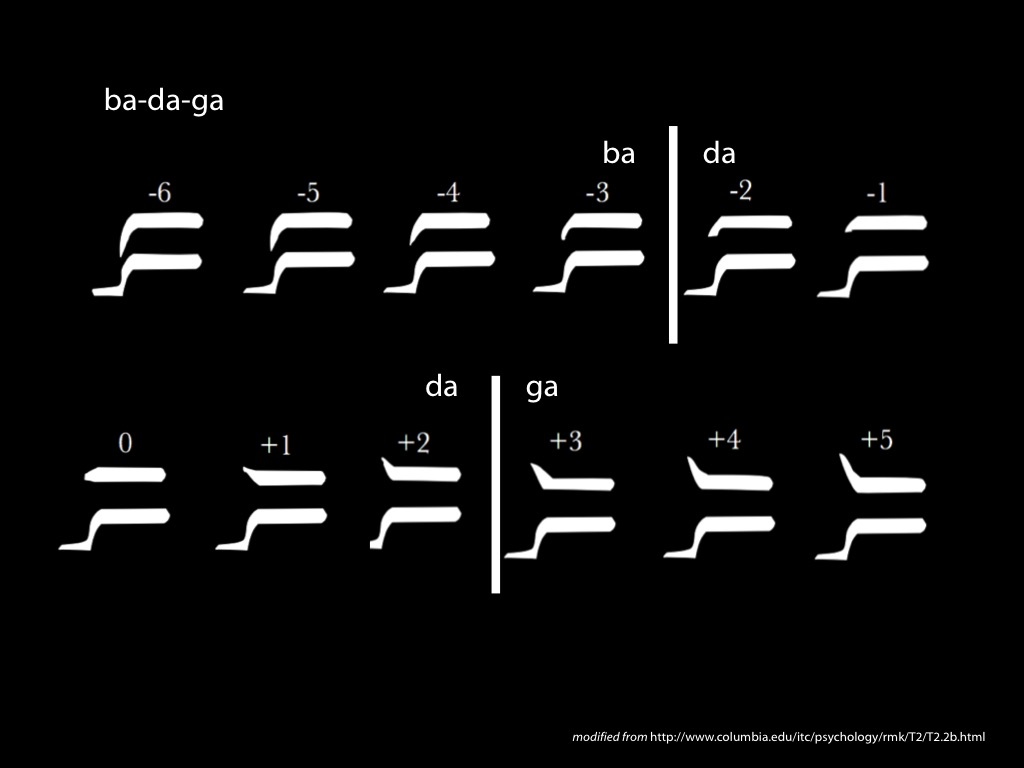

How do we know that the same stimuli may be processed by different perceptual systems

concurrently—for instance, how do we know that speech and auditory processing are distinct? A

phenomenon called “duplex” perception demonstrates their distinctness occurs in. Artificial

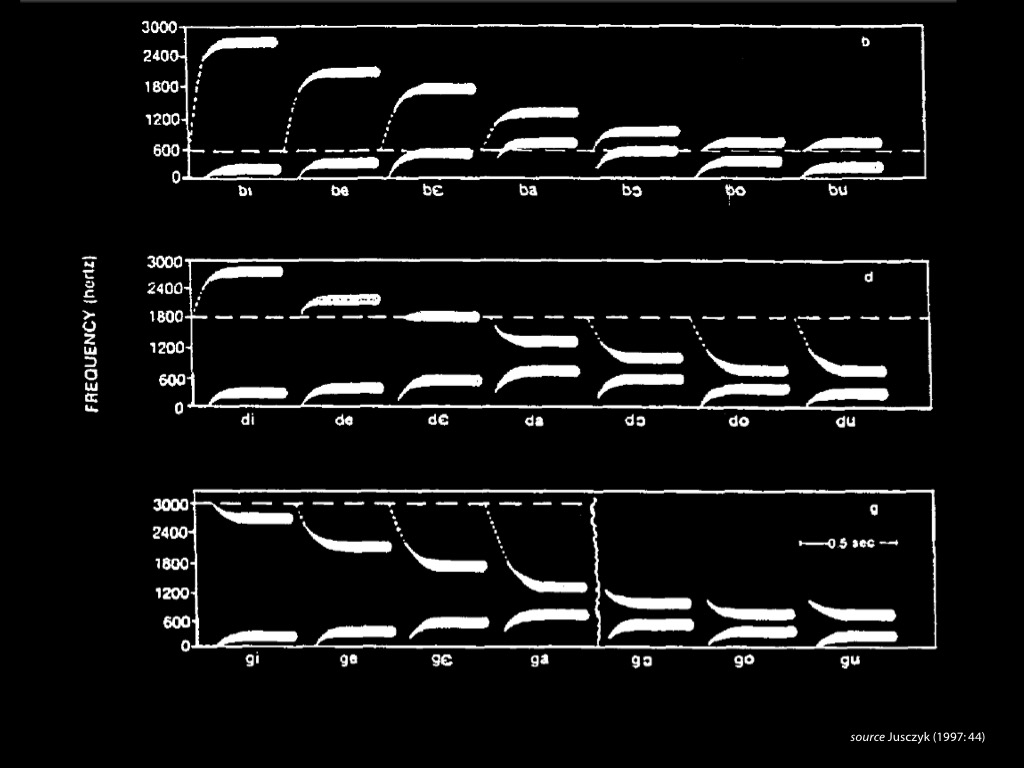

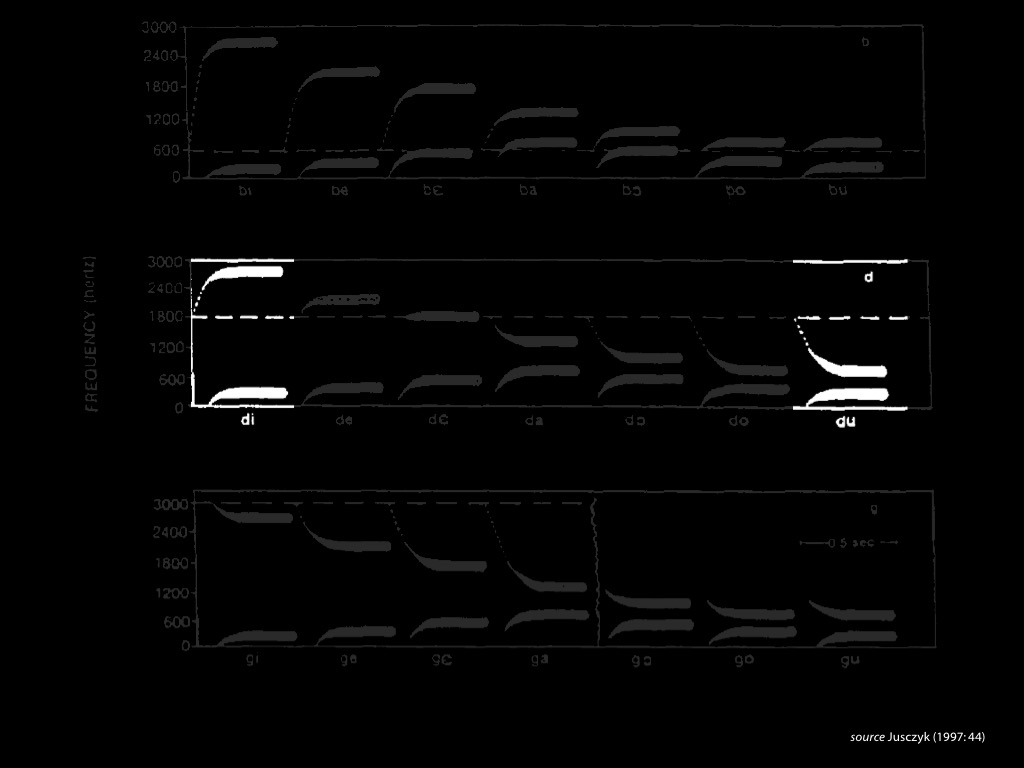

speech-like stimuli for two syllables, [ra] and [la], are generated. The acoustic signals for each

syllable is artificially broken up into two parts, the “base” and “transition” (see Fig. *** below).

The syllables have the same “base” but differ in the “transition”. When the “transition” is played

alone it sounds like a chirp and quite unlike anything we normally hear in speech. Duplex perception

occurs when the base and transition are played together but in separate ears. In this case, subjects

hear both the chirp that they hear when the transition is played in isolated, and the syllable [la]

or [ra]. Which syllable they hear depends on which transition is played, so speech processing must

have combined the base and transition. By contrast, auditory processing must have failed to combine

them because otherwise the chirp would not have been heard. In this case, then, the perception

resulting from the duplex presentation involves simultaneous auditory and speech recognition

processes. This shows that auditory and speech processing are distinct perceptual processes.

The duplex case is unusual. We can’t normally hear the chirps we make in speaking because speech

processing inhibits this level of auditory processing. But plainly speech is subject to some auditory

processing for we can hear extra-linguistic qualities of speech; some of these provide cues to

emotional state, gender and class. Perception of these extra-linguistic qualities enables us to

distinguish stimuli within a category. As already mentioned, this is a problem for Repp’s operational

definition. Our ability to discriminate stimuli is the product of both categorical speech processing

and non-categorical auditory processing. If we want to get at the essence of categorical perception

it seems there is no alternative but to appeal to particular perceptual processes rather than

behaviours.

Source: \citep{Liberman:1981xk}