Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Five Complications

five complications

This isn’t a preliminary to my talk; although I will say something about how to solve

the interface problem right at the end, I’m mainly concerned to persuade you that

the interface problem is tricky to solve.

1

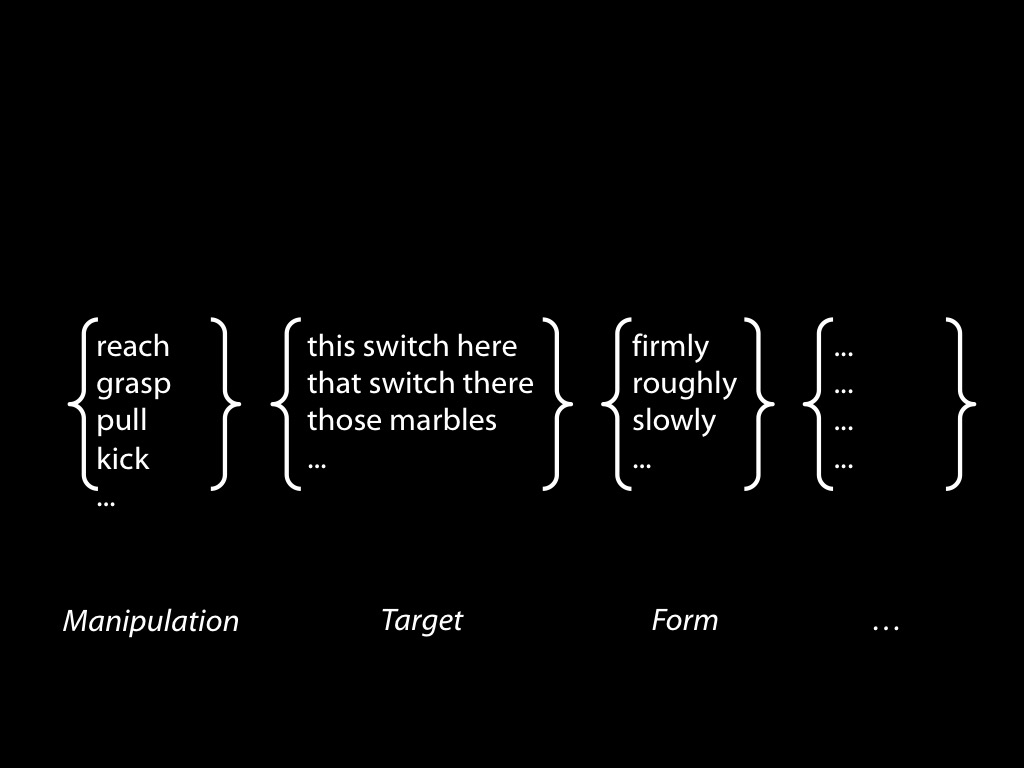

First consideration which complicates the interface problem: outcomes have a complex anatomy

comprising manipulation, target, form and more.

There is evidence that each of these can be represented motorically; and of course these

can all be specified by intentions too.

On the targets of actions, as Elisabeth has stressed,

motor representations represent not only ways of acting but also targets on which actions

might be performed and some of their features related to possible action outcomes involving

them (for a review see Gallese & Sinigaglia 2011; for discussion see Pacherie 2000, pp.

410-3). For example visually encountering a mug sometimes involves representing features

such as the orientation and shape of its handle in motor terms (Buccino et al. 2009;

Costantini et al. 2010; Cardellicchio et al. 2011; Tucker & Ellis 1998, 2001).

One possibility is that the Interface Problem breaks down into questions corresponding

to these three different components of outcomes. That is, an account of how the manipuations

specified by intentions and motor representations nonaccidentally match might end up being

quite different from an account of how the targets or forms match.

(I’m not saying this is right, just considering the possibility.)

2

phase shift

period shift

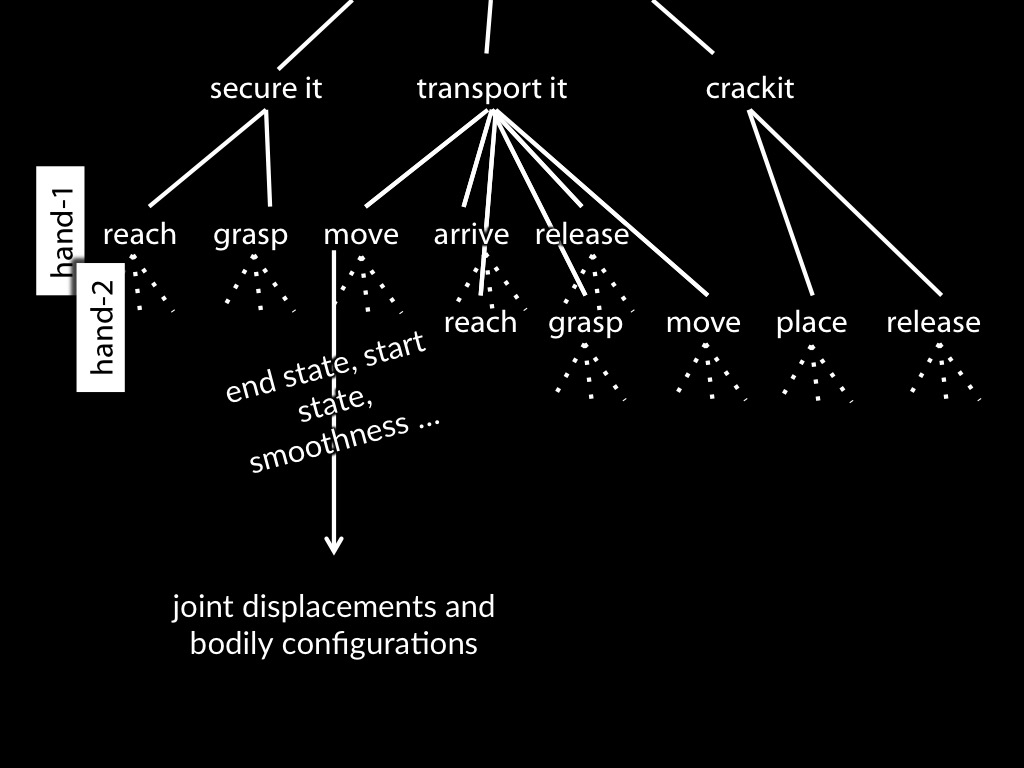

Second consideration which complicates the interface problem: scale.

This shows that we can’t think of the interface problem merely as a way of intentions

setting problems to be solved by motor representations: there may be multiple intentions

at different scales, and in some cases an intention may operate at a smaller scale than

a motor representation.

Suppose you have an intention to tap in time with a metronome.

Maintaining synchrony will involve two kinds of correction: phase and period shifts.

These appear appear to be made by mechanisms acting independently, so that correcting errors involves a distinctive pattern of overadjustment.

Adjustments involving phase shifts are largely automatic, adjustments involving changes in period are to some extent controlled.

How are period shifts controlled?

Importantly this is not currently known.

One possibility is that period adjustments can be made intentionally \citep[as][p.~2599 hint]{fairhurst:2013_being};

another is that there are a small number of ‘coordinative strategies’ \citep{repp:2008_sensorimotor} between which agents with sufficient skill can intentionally switch in something like the way in which they can intentionally switch from walking to running.

But either way, there can be two intentions: a larger-scale one to tap in time with a metronome

and a smaller-scale one to adjust the tapping which results in a period shift.

EP: Skilled piano playing means being able to have intentions with respect to larger units than a

novice could manage. But in playing a 3-voice fugue you may need to pay attention to a particular

nger in order to keep the voices separate. So you need to be able to attend to both ‘large chunks’

(e.g. chords) of action and ‘small chunks’ (e.g. keypresses) simultaneously.

BACKGROUND:

Because no one can perform two actions without introducing some tiny variation between them, entrainment of any kind depends on continuous monitoring and ongoing adjustments \citep[p.~976]{repp:2005_sensorimotor}.

% \textcite[p.~976]{repp:2005_sensorimotor}: ‘A fundamental point about SMS is that it cannot be sustained without error correction, even if tapping starts without any asynchrony and continues at exactly the right mean tempo. Without error correction, the variability inherent in any periodic motor activity would accumulate from tap to tap, and the probability of large asynchronies would increase steadily (Hary & Moore, 1987a; Voillaume, 1971; Vorberg & Wing, 1996). The inability of even musically trained participants to stay in phase with a virtual metronome (i.e., with silent beats extrapolated from a metronome) can be demonstrated easily in the synchronization–continuation paradigm by computing virtual asynchronies for the continuation taps. These asynchronies usually get quite large within a few taps, although occasionally, virtual synchrony may be maintained for a while by chance.’

% \citet[p.~407]{repp:2013_sensorimotor}: ‘Error correction is essential to SMS, even in tapping with an isochronous, unperturbed metronome.’

One kind of adjustment is a phase shift, which occurs when one action in a sequence is delayed or brought forwards in time.

Another kind of adjustment is a period shift; that is, an increase or reduction in the speed with which all future actions are performed, or in the delay between all future adjacent pairs of actions.

These two kinds of adjustment,

phase shifts and period shifts,

appear to be made by mechanisms acting independently, so that correcting errors involves a distinctive pattern of overadjustment.%

\footnote{%

See \citet[pp.~474–6]{schulze:2005_keeping}. \citet{keller:2014_rhythm} suggest, further, that the two kinds of adjustment involve different brain networks.

Note that this view is currently controversial: \citet{loehr:2011_temporal} could be interpreted as providing evidence for a different account of how entrainment is maintained.

}

\citet[p.~987]{repp:2005_sensorimotor} argues, further, that while adjustments involving phase shifts are largely automatic, adjustments involving changes in period are to some extent controlled.

% (‘two error correction processes, one being largely automatic and operating via phase resetting, and the other being mostly under cognitive control and, presumably, operating via a modulation of the period of an internal timekeeper’ \citep[p.~987{repp:2005_sensorimotor})

One possibility is that period adjustments can be made intentionally \citep[as][p.~2599 hint]{fairhurst:2013_being};

another is that there are a small number of ‘coordinative strategies’ \citep{repp:2008_sensorimotor} between which agents with sufficient skill can intentionally switch in something like the way in which they can intentionally switch from walking to running.

2

So it is not that intentions are restricted to specifying outcomes which form the head of the means-end

hierarchy of outcomes represented motorically.

They can also influence aspects of outcomes at smaller scales.

3

Third consideration which complicates the interface problem: dynamics.

It’s ‘not just how motor representations are triggered by intentions, but how motor representations’ sometimes nonaccidentally continue to match intentions as circumstances change in unforeseen ways ‘throughout skill execution’

\citep[p.~19]{fridland:2016_skill}.

Fridland, 2016 p. 19

Here we need to distinguish different kinds of change.

Some changes can be flexibly accommodated motorically without any need for intention

to be involved, or even for the agents to be aware of the change. This includes peturbations

in the apparent direction of motion while drawing \citep{fourneret:1998_limited}.

But other changes may require a change in intention: circumstances may change in such a way

that you wish either to abandon the action altogether, or else switch target midway through.

\textbf{KEY}: in executing an intention you may learn something which causes you to change

your intention; for example, you may learn that the action is just too awkward, or that the

ball is out of reach. So motor processes can result in discoveries that nonaccidentally cause

changes in intention.

This also shows that we can’t think of the interface problem merely as a way of intentions

‘handing off’ to motor representations: in some cases, the matching of motor representations

and intentions will nonaccidentally persist.

unidirectional bidirectional

These reflections on dynamics (and on scale too[?]) suggest that the interface problem

is not a unidirectional but a bidirectional one. The agent who intends probably cannot be blind to

the ways in which motor representations structure her actions since the structure is both provides

and limits opportunities for interventions.

4

The interface problem is the problem of explaining how there could be nonaccidental matches.

But there is a related developmental problem: What is the process by which humans acquire

abilities to ensure that their intentions and motor representations sometimes nonaccidentally

match?

A solution to the interface problem must provide a framework for answering the corresponding

question about development.

5

imagining acting

Imagination: intentions and motor representations can nonaccidentally match not only

when we are acting but also when we are merely imagining acting.