Start with a case in which behaviour reading is clearly involved.

I take Byrne’s study

to demonstrate that chimps are capable of sophisticated behaviour reading.

But how might they represent behaviours?

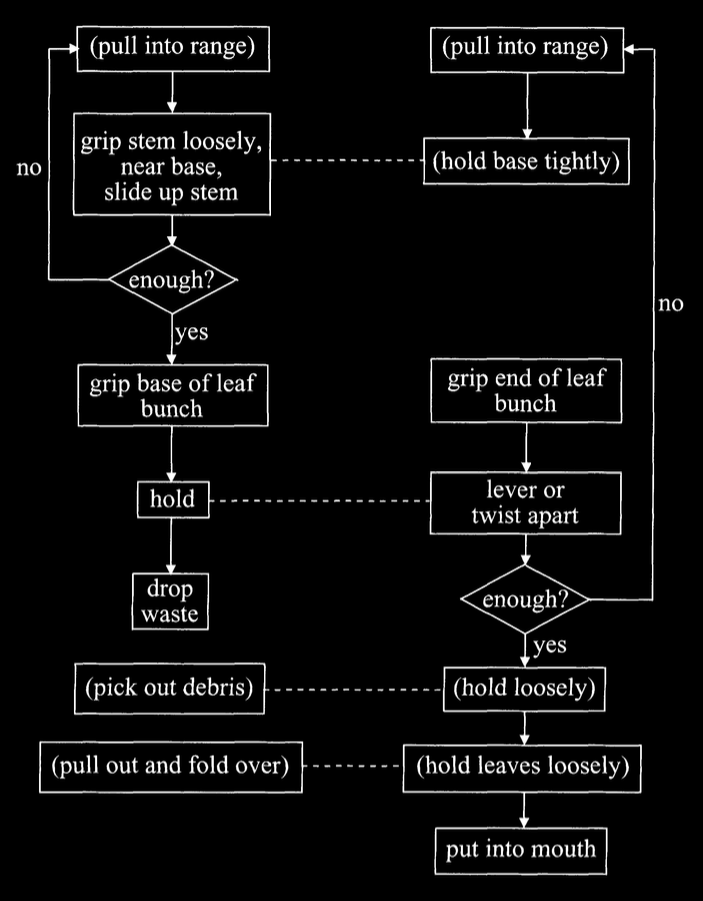

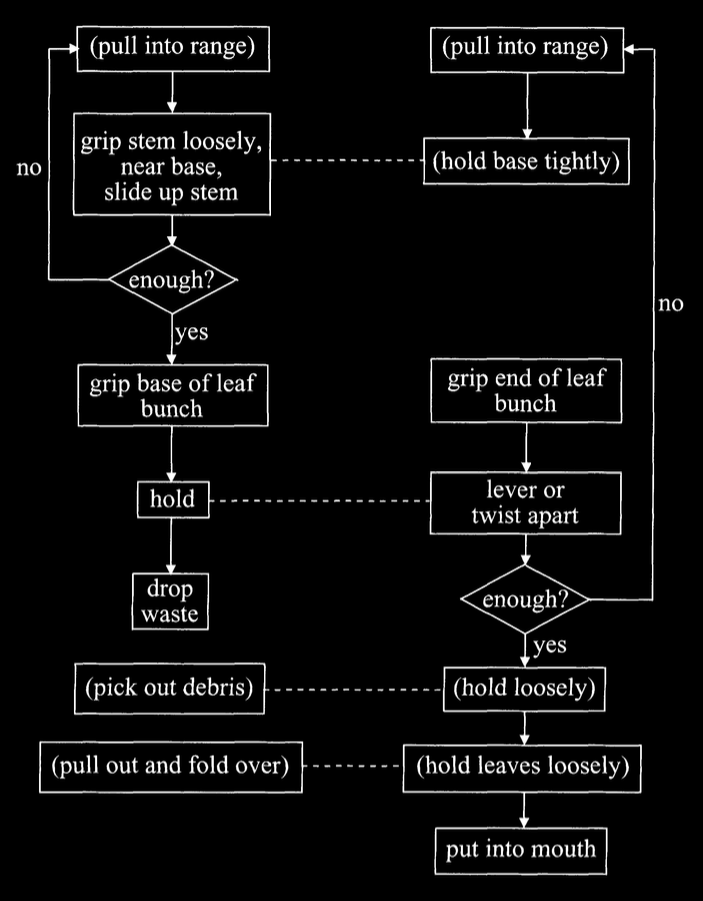

The procedure for preparing a nettle to eat while avoiding contact with its stings is shown in

\vref{fig:byrne_2003_fig1}. It involves multiple steps. Some steps may be repeated varying numbers of

times, and not all steps occur in every case. The fact that gorillas can learn this and other

procedures for acquiring and preparing food by observing others’ behaviour suggests that they have

sophisticated behaviour reading abilities \citep[p.~513]{Byrne:2003wx}. If we understood the nature

of these behaviour reading abilities and their limits, we might be better able to understand their

abilities to track mental states too.

Byrne 2003, figure 1

‘great apes [are] able to acquire complex and elaborate local traditions of food

acquisition, some of them involving tool use’ \citep[p~513]{Byrne:2003wx}

So even quite sophisticated behaviour reading is possible without any

reliance on communication by language.

We can therefore think of behaviour reading as foundational for any kind

of radical interpretation.

[background]

‘Nettles, Laportea alatipes, are an important food of mountain gorillas in Rwanda (Watts 1984),

rich in protein and low in secondary compounds and structural carbohydrate (Waterman et al. 1983).

Unfortunately for the gorillas, this plant is 'defended' by powerful stinging hairs,

especially dense on the stem, petioles and leaf-edges.

All gorillas in the local population process nettles in broadly the same way,

a technique that minimizes contact of sting- ing hairs with their hands and

lips (Byrne & Byrne 1991; figure 1). A series of small transformations is

made to plant material: stripping leaves off stems, accumulating

larger bundles of leaves, detachment of petioles, picking out unwanted debris,

and finally folding a package of leaf blades within a single leaf before

ingestion. The means by which each small change is made are idiosyncratic and

variable with context (Byrne & Byrne 1993), thus presum- ably best learned

by individual experience. However, the overall sequence of five discrete

stages in the process is standardized and appears to be essential for efficiency

(Byrne et al. 2001a).’ \citep[pp.~531--2]{Byrne:2003wx}

‘Like other complex feeding tasks in great apes, preparing nettles is a hierarchically

organized skill, showing considerable flexibility: stages that are occasionally

unnecessary are omitted, and sections of the process (of one or several ordered stages)

are often repeated iteratively to a criterion apparently based on an adequate size of

food bundle (Byrne & Russon 1998).’ \citep[pp.~532]{Byrne:2003wx}