some

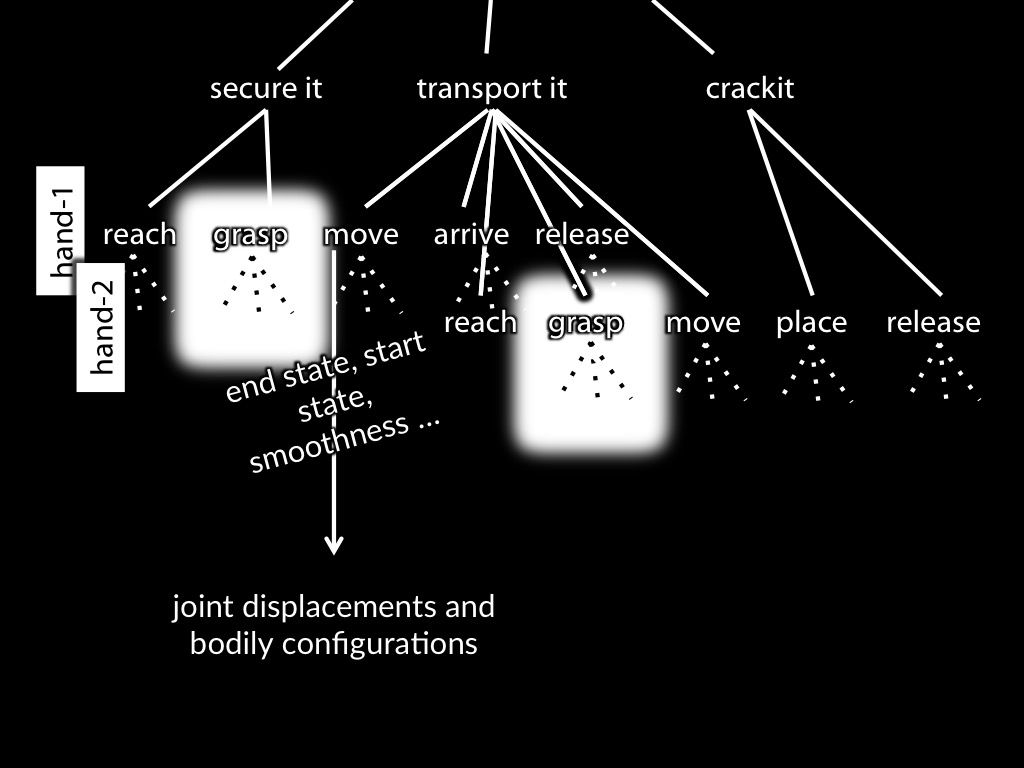

motor representations (/schema) represent ???outcomes = goals

‘a given motor act may change both as a function of what motor act will follow it—a sign of

planning—and as a function of what motor act preceded it—a sign

of memory’ \citep[p.~294]{cohen:2004_wherea}.

‘a given motor act may change ... as a function of what motor act will follow it—a sign of

planning’

Cohen & Rosenbaum 2004, p. 294

Let me go back and start with some almost uncontroversial facts about motor representations and

their action-coordinating role.

Why postulate motor representations at all? [Dependence of present actions on future actions

is one reason for doing so.]

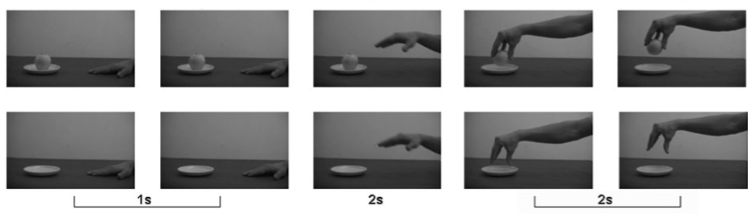

Suppose you are a cook who needs to take an egg from its box, crack it and put it (except for the

shell) into a bowl ready for beating into a carbonara sauce.

Even for such mundane, routine actions, the constraints on adequate performance can vary

significantly depending on subtle variations in context. For example, the position of a hot pan

may require altering the trajectory along which the egg is transported, or time pressures may mean

that the action must be performed unusually swiftly on this occasion.

Further, many of the constraints on performance involve relations between actions occurring at

different times.

To illustrate, how tightly you need to grip the egg now depends, among other things, on the forces

to which you will subject the egg in lifting it later.

It turns out that people reliably grip objects such as eggs just tightly enough across a range of

conditions in which the optimal tightness of grip varies.

This indicates (along with much other evidence) that information about the cook’s anticipated

future hand and arm movements appropriately influences how tightly she initially grips the egg

(compare \citealp{kawato:1999_internal}).

This anticipatory control of grasp,

like several other features of action performance (\citealp[see][chapter 1]{rosenbaum:2010_human} for more examples),

is not plausibly a consequence of mindless physiology, nor of intention and practical reasoning.

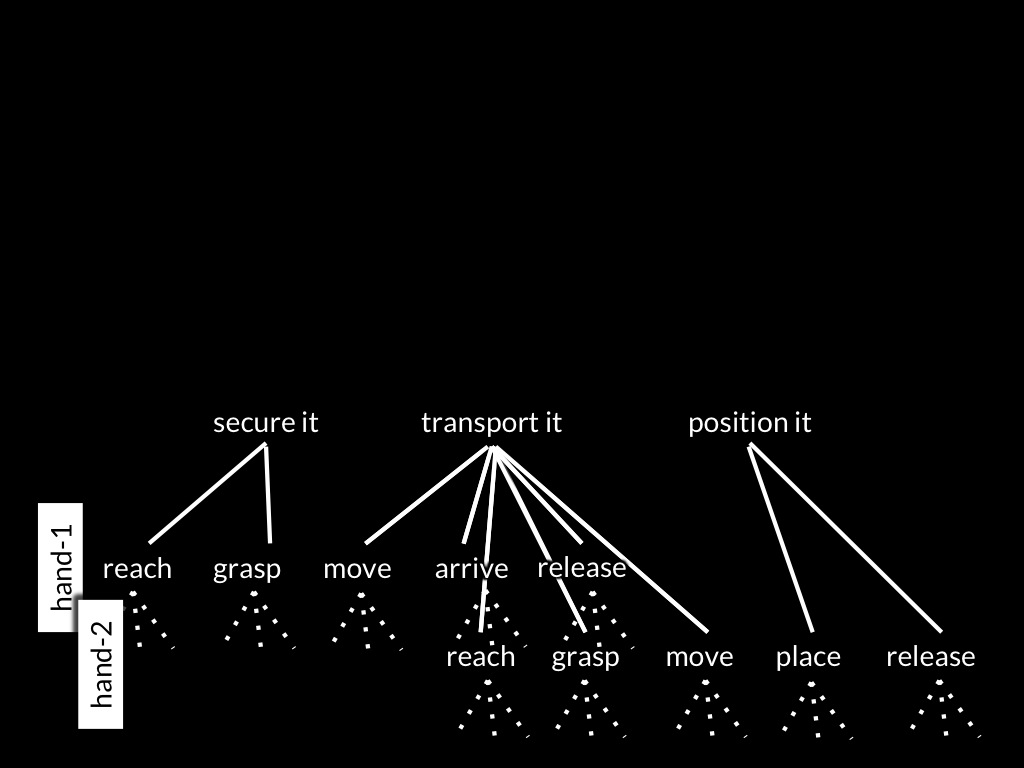

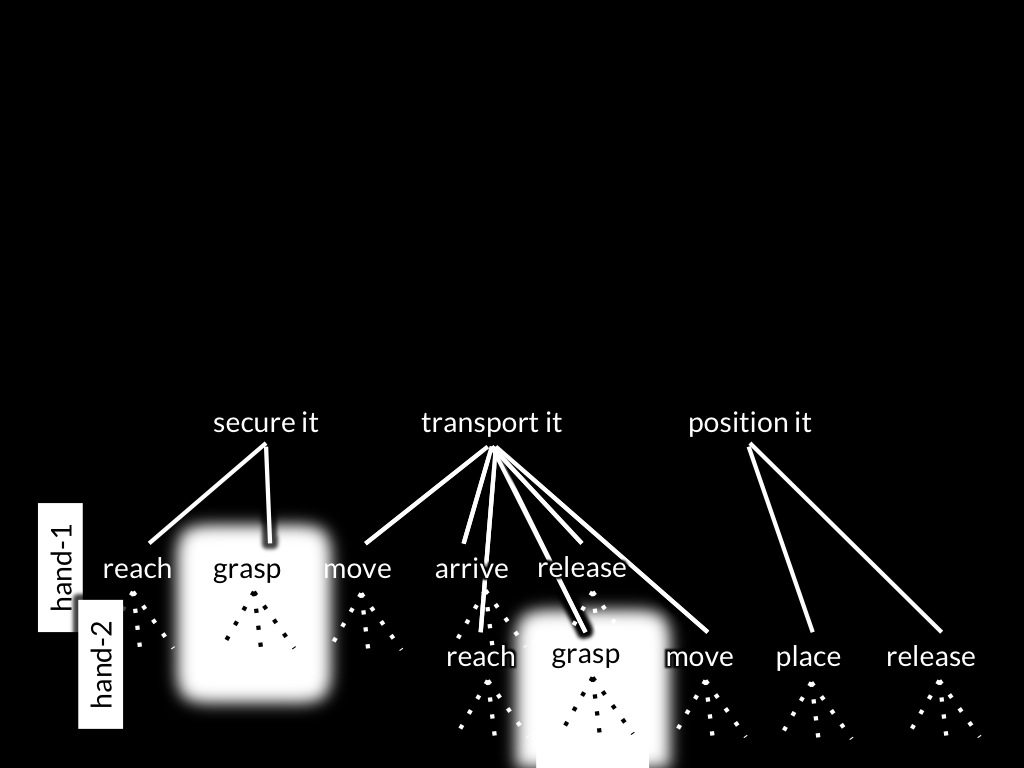

This is one reason for postulating motor representations, which characteristically play a role in

coordinating sequences of very small scale actions such as grasping an egg in order to lift it.

[The scale of an actual action can be defined in terms of means-end relations.

Given two actions which are related as means to ends by the processes and representations

involved in their performance, the first is smaller in scale than the second just if the

first is a means to the second. Generalising, we associate the scale of an actual action

with the depth of the hierarchy of outcomes that are related to it by the transitive closure

of the means-ends relation. Then, generalising further, a repeatable action (something that

different agents might do independently on several occasions) is associated with a scale

characteristic of the things people do when they perform that action. Given that actions

such as cooking a meal or painting a house count as small-scale actions, actions such as

grasping an egg or dipping a brush into a can of paint are very-small scale. Note that we

do not stipulate a tight link between the very small scale and the motoric. In some cases

intentions may play a role in coordinating sequences of very small scale purposive actions,

and in some cases motor representations may concern actions which are not very small scale.

The claim we wish to consider is only that, often enough, explaining the coordination of

sequences of very small scale actions appears to involve representations but not, or not

only, intentions. To a first approximation, \emph{motor representation} is a label for

such representations.%

\footnote{%

Much more to be said about what motor representations are; for instance, see \citet{butterfill:2012_intention} for the view that motor representations can be distinguished by representational format.

}]

‘a given motor act may change both as a function of what motor act will follow it—a sign of

planning—and as a function of what motor act preceded it—a sign

of memory’ \citep[p.~294]{cohen:2004_wherea}.

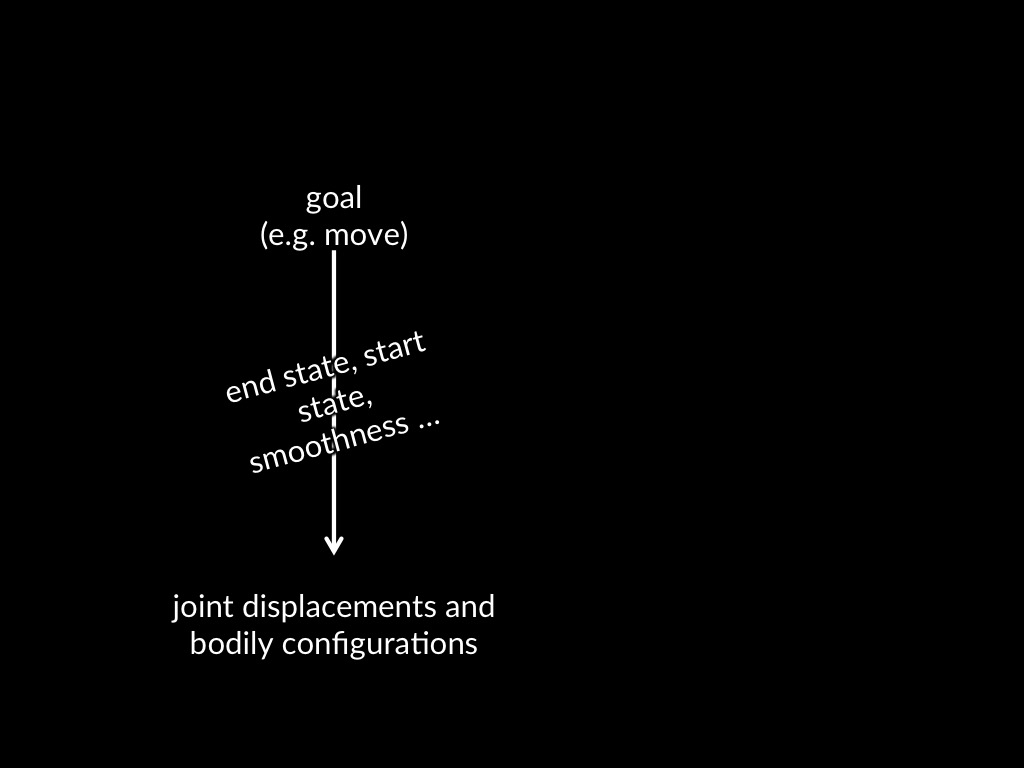

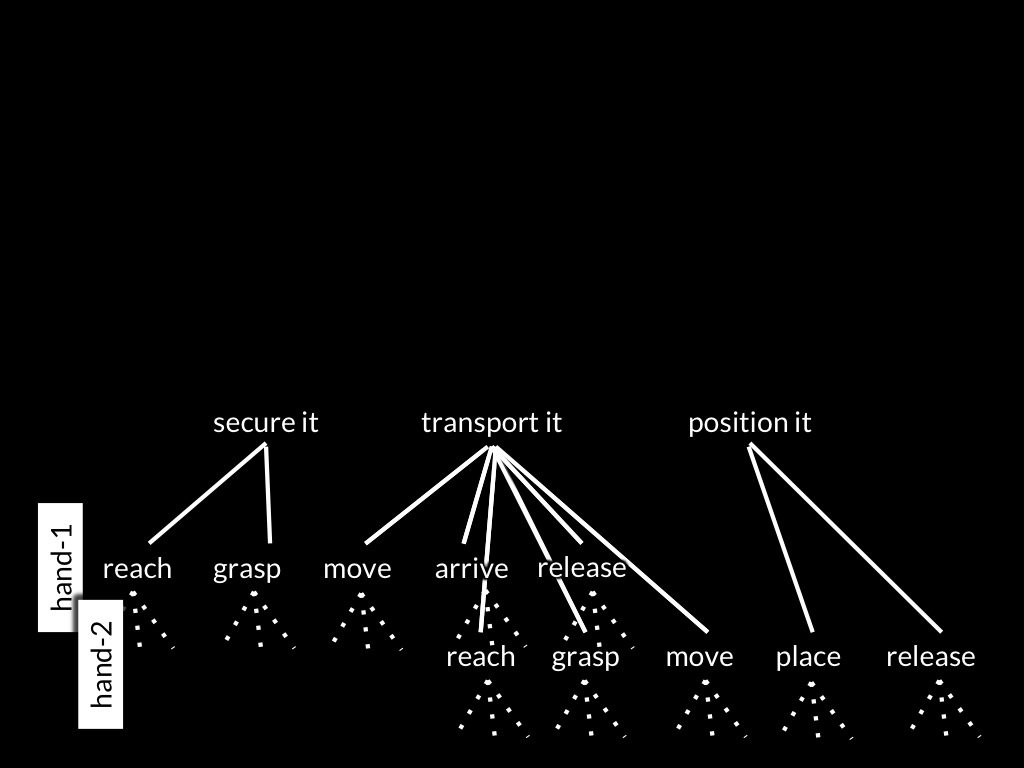

What do motor representations represent? An initially attractive, conservative

view would be that they represent bodily configurations and joint displacements,

or perhaps sequences of these, only.

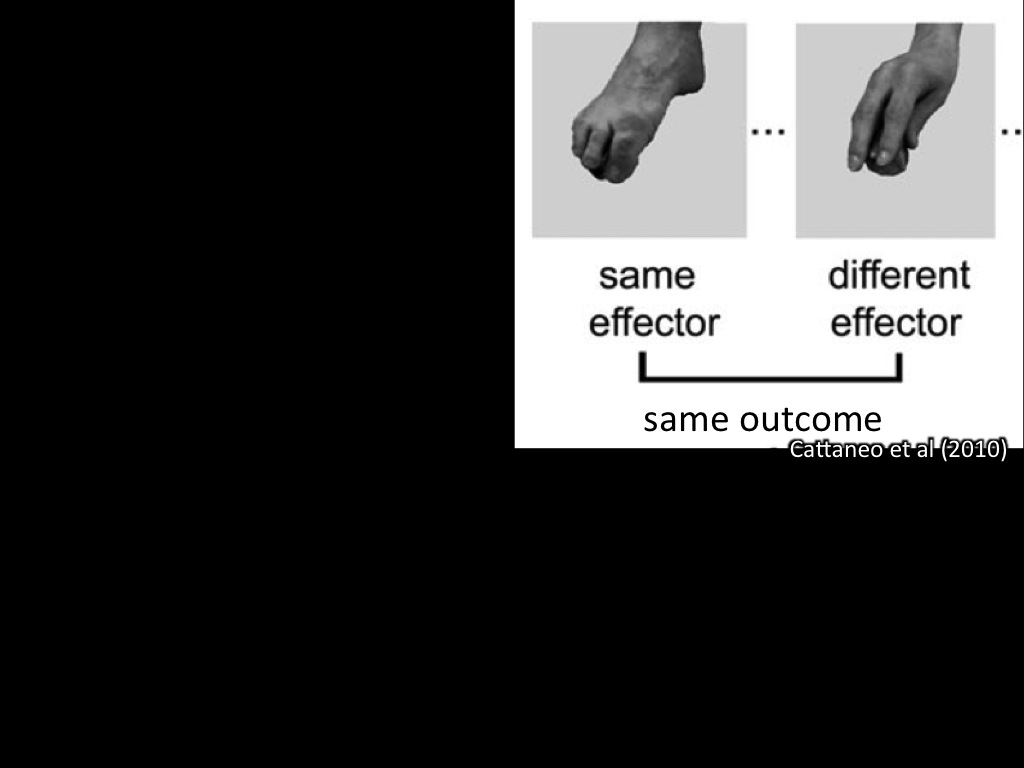

However there is now a significant body of evidence that some motor representations

do not specify particular sequences of bodily configurations and joint displacements,

but rather represent outcomes such as the grasping of an egg or the pressing of a switch.

These are outcomes which might, on different occasions, involve very different bodily

configurations and joint displacements

(see \citealp{rizzolatti_functional_2010} for a selective review).

Such outcomes are abstract relative to bodily configurations and joint displacements

in that there are many different ways of achieving them.

Since this is important, let me pause for a moment.

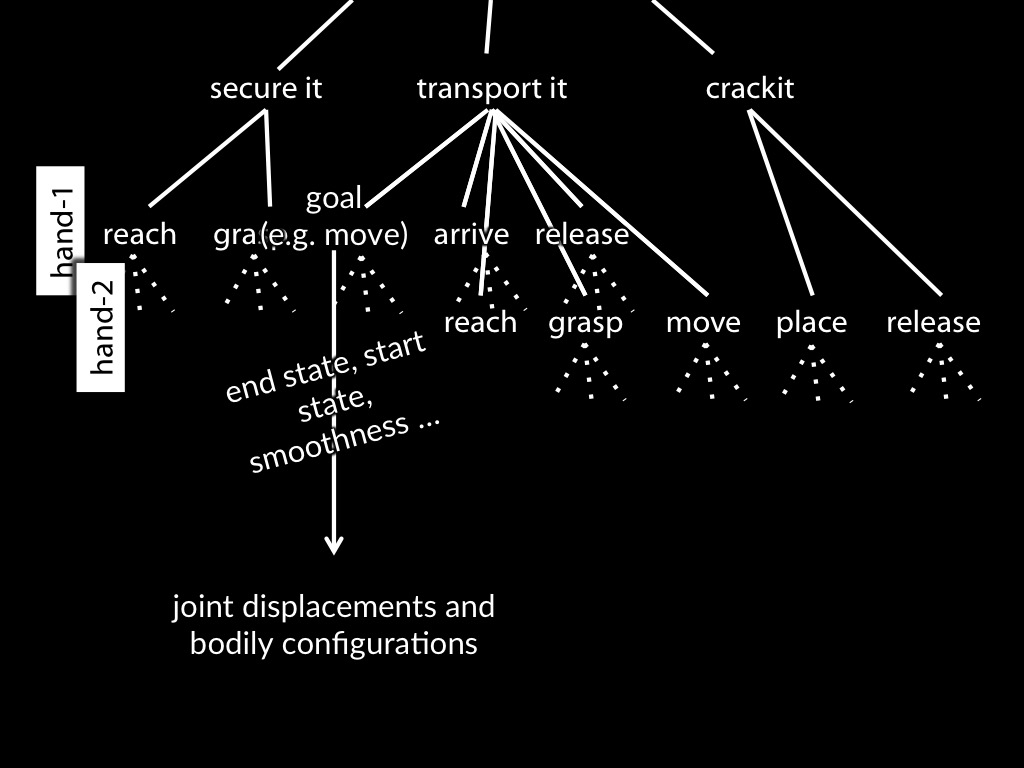

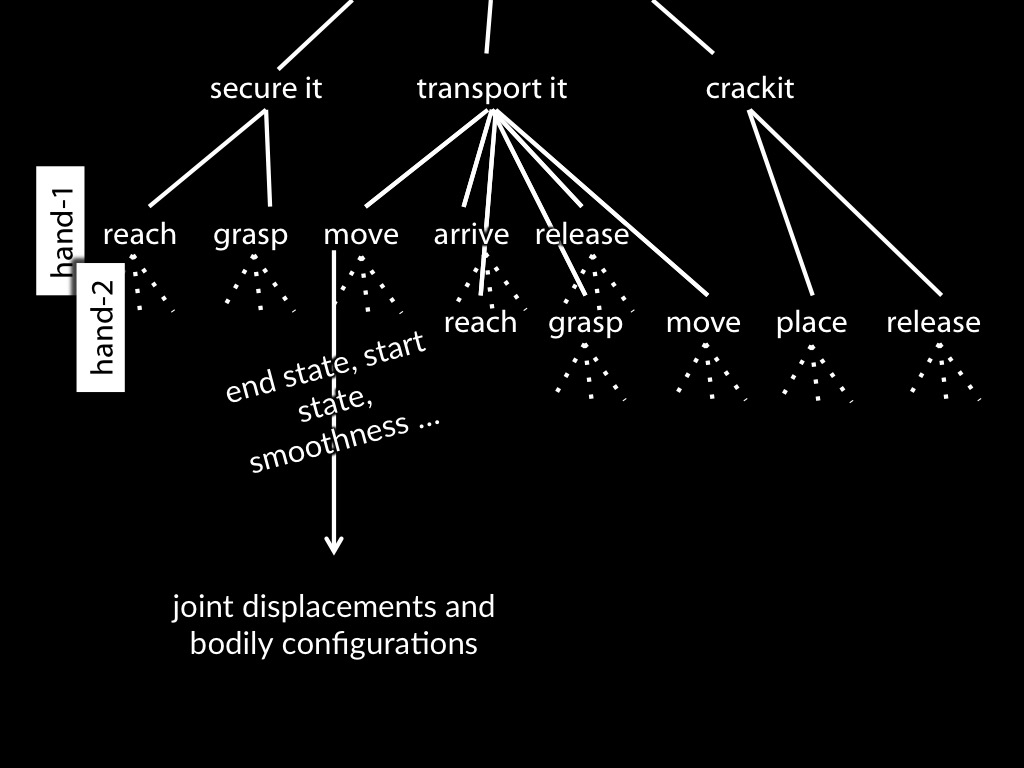

To say that something is an outcome is not to say very much: merely that it is a

possible or actual state of affairs which is brought about in some way by an action.

What I mean is that motor representations represent the sort of outcomes that are plausibly

thought of as goals of actions, things such as transporting and breaking an egg,

or flipping a switch.

This kind of outcomes are quite different from both patterns of joint displacement and

bodily movements and also from end states.

In my terms, a goal is merely outcome.

Contrast goals with goal-states, which are mental or functional states which specify goals.

A motor representation is a goal-state; the goal is the thing it represents.

Motor schema are just motor representations which specify incomplete outcomes.

[Of course schema are incomplete, so do not specify outcomes but outcome types.]

Motor schema are ‘internal models or stored representations that represent generic knowledge about

a certain pattern of action and are implicated in the production and control of action’

\citep{mylopoulos:2016_intentions}.

‘Motor schemas are more abstract and stable representations of actions than motor

representations.’

‘They are internal models or stored representations that represent generic knowledge

about a certain pattern of action and are implicated in the production and control of

action. For instance, in the influential Motor Schema Theory proposed by Richard Schmidt

(1975, 2003), a motor schema involves a generalized motor program, together with corre-

sponding ‘recall’ and ‘recognition’ schemas. The generalized motor program is thought to

contain an abstract representation defining the general form or pattern of an action,

that is the organization and structure common to a set of motor acts (e.g., invariant

features pertaining to the order of events, their spatial configuration, their relative

timing and the relative force with which they are produced). This generalized motor

program has parameters that control it. In order to determine how an action should be

performed on a given occasion, parameter values adapted to the situation must be

specified. Thus, a motor schema also includes a rule or system of rules describing the

relationships between initial conditions, parameter values and outcomes and allowing us

to perform the action over a large range of conditions (the ‘recall schema’ in Schmidt’s

terminology). Finally, the motor schema also includes a rule or system of rules

describing the relationships between initial conditions, exteroceptive and propri-

oceptive sensory feedback during an action, and action outcome (a recognition sche- ma),

allowing agents to know when they have made an error – i.e., the action does not have

the sensory consequences it is expected to have – and to correct for it.’

Are motor schemas an alterantive to motor representations? Tempting to think that where

they talk about motor schema, we think of motor representations that represent outcomes

that are relatively distal from action (e.g. are affector-neutral).

This would explain why they contrast motor schema with motor programmes. We use ‘motor

representation’ to include both.