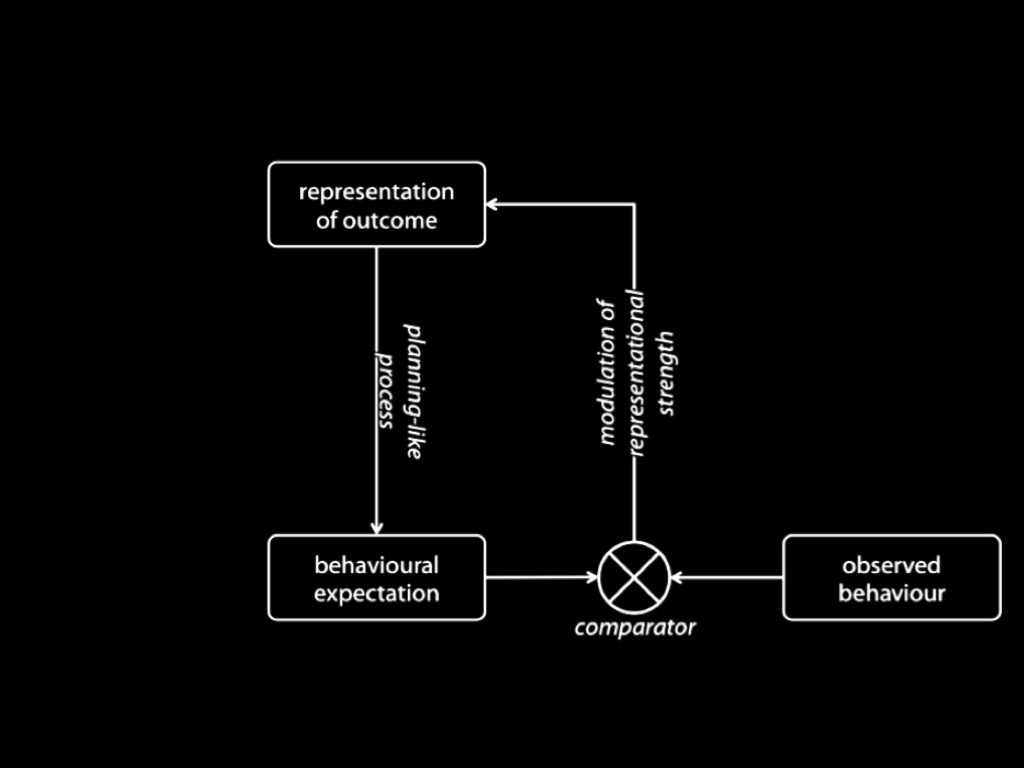

And we conjecture that the result of this comparison modulates the strength of the motor representation of the outcome.

Within limits, this modulation will ensures that an outcome represented motorically is likely to be a goal of the observed action.

In this way, motor representations enable goal tracking.

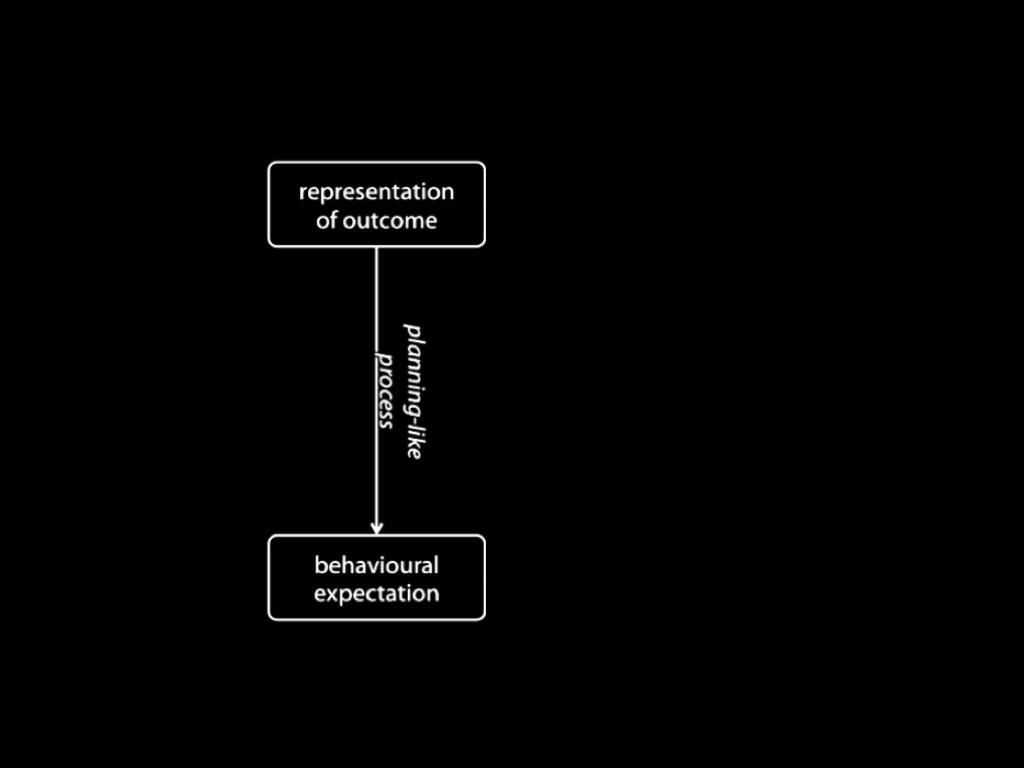

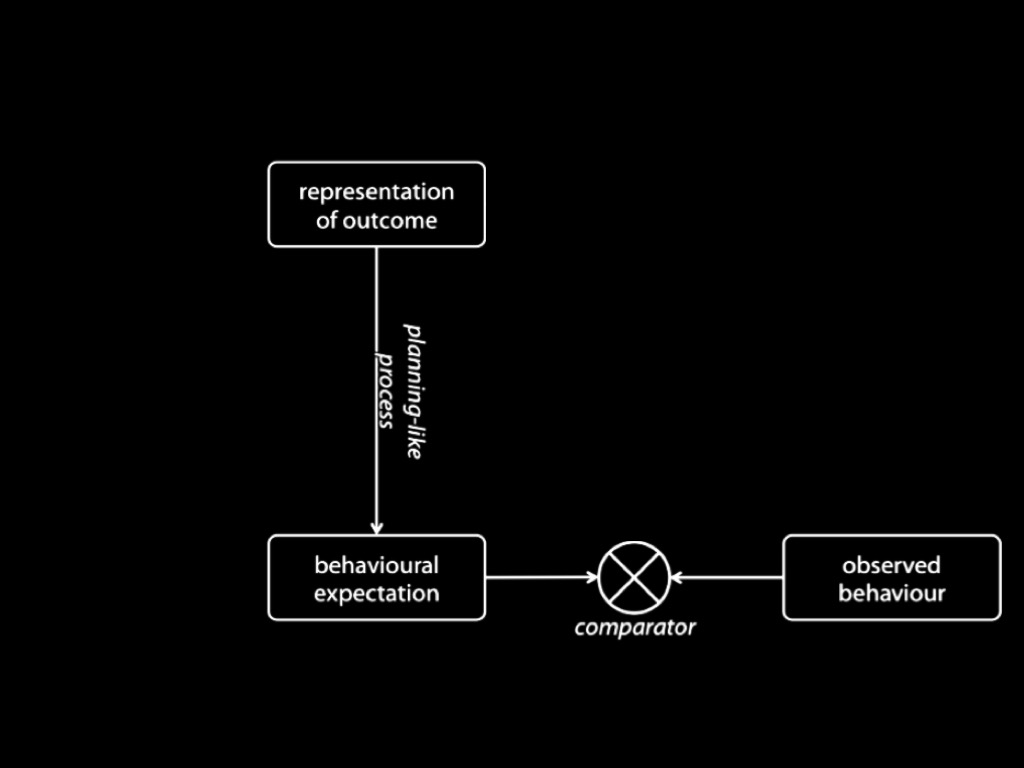

Sinigalia & Butterfill 2015, figure 1

Goal-tracking is acting in reverse.

-- in action observation, possible outcomes of observed actions are represented

-- these representations trigger planning as if performing actions directed to the outcomes

-- such planning generates predictions

-- a triggering representation is weakened if its predictions fail

The result is that the only only outcomes to which the observed action is a means

are represented strongly.

There is evidence that a motor representation of an outcome can cause a determination of which

movements are likely to be performed to achieve that outcome \citep[see, for

instance,][]{kilner:2004_motor, urgesi:2010_simulating}. Further, the processes involved in

determining how observed actions are likely to unfold given their outcomes are closely related,

or identical, to processes involved in performing actions.

This is known in part thanks to studies of how observing actions can facilitate performing

actions congruent with those observed, and can interfere with performing incongruent actions

\citep{

brass:2000_compatibility,

craighero:2002_hand,

kilner:2003_interference,

costantini:2012_does}.

Planning-like processes in action observation have also been demonstrated by measuring observers' predictive gaze. If you were to observe just the early phases of a grasping movement, your eyes might jump to its likely target, ignoring nearby objects \citep{ambrosini:2011_grasping}. These proactive eye movements resemble those you would typically make if you were acting yourself \citep{Flanagan:2003lm}.

Importantly, the occurrence of such proactive eye movements in action observation depends on your

representing the outcome of an action motorically; even temporary interference in the observer's

motor abilities will interfere with the eye movements \citep{Costantini:2012fk}.

These proactive eye movements also depend on planning-like processes; requiring the observer to

perform actions incongruent with those she is observing can eliminate proactive eye movements

\citep{Costantini:2012uq}. This, then, is further evidence for planning-like motor processes in

action observation.

So observers represent outcomes motorically and these representations trigger planning-like processes

which generate expectations about how the observed actions will unfold and their sensory consequences.

Now the mere occurrence of these processes is not sufficient to explain why, in action observation,

an outcome represented motorically is likely to be an outcome to which the observed action is

directed.

To take a tiny step further, we conjecture that, in action observation, \textbf{motor representations of

outcomes are weakened to the extent that the expectations they generate are unmet}

\citep[compare][]{Fogassi:2005nf}.

A motor representation of an outcome to which an observed action is not directed is likely to

generate incorrect expectations about how this action will unfold, and failures of these

expectations to be met will weaken the representation.

This is what ensures that there is a correspondence between outcomes represented motorically in

observing actions and the goals of those actions.