‘As defined by Tutiya et al., an executable concept of a type of movement is a

representation, that could guide the formation of a volition, itself the proximal cause of

a corresponding movement. Possession of an executable concept of a type of movement thus

implies a capacity to form volitions that cause the production of movements that are

instances of that type.’

\citep[p.~7]{pacherie:2011_nonconceptual}

Mylopoulos and Pacherie:

‘an executable [action] concept of a type of movement is a representation, that could guide the formation of a volition, itself the proximal cause of a corresponding movement.

Possession of an executable concept of a type of movement thus implies a capacity to form volitions that cause the production of movements that are instances of that type.’

There explanation: two different kinds of action concept, one purely

observational.

‘For instance, most of us have a concept of ‘tail wagging’ that we can deploy when we

judge, for instance, that Julius the dog is wagging his tail. Or if you are not

convinced that tail wagging constitutes purposive behavior, consider the action concept

‘tail swinging’, as in ‘cows constantly swing their tails to flick away flies’.’

Pacherie 2011, p. 8

Objections:

(i) It looks like the executable action concept builds in a solution to the interface problem

rather than solving it.

The executable action concept is a ready-made solution.

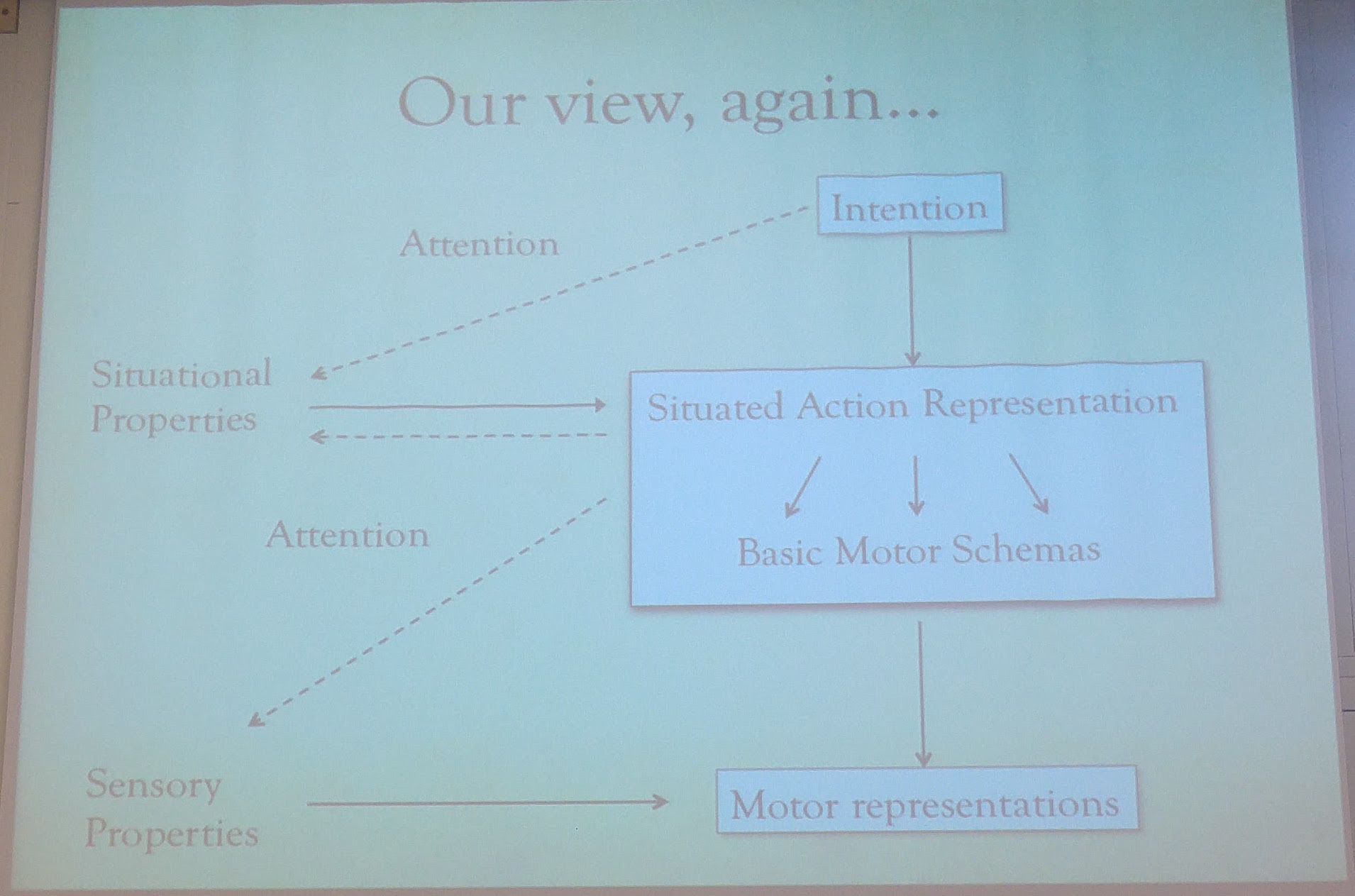

To answer this objection, we need an account of how concepts and motor representations

become bound together.

Simple theory of executable action concepts:

there are concept--motor schema associations.

REPLY: Simple theory of executable action concepts: they’re just associations between

concepts and motor schema (partially specified outcomes that are represented motorically).

[Objections (ctd):

(ii) Fridland: there is a dynamic component to the interface problem.

An an answer to it must specify ‘not just how motor representations are triggered by

intentions, but how motor representations’ continue to match intentions as circumstances

change in unforeseen ways ‘throughout skill execution’ (Fridland, 2016 p. 19).]

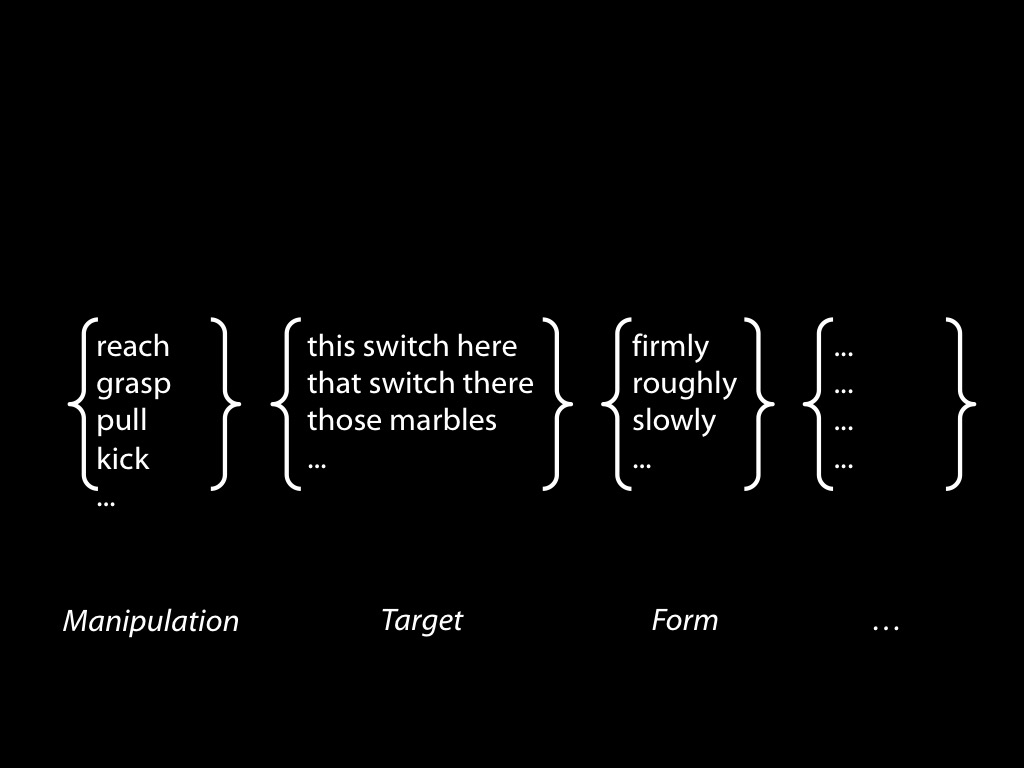

(iii) We need to understand how there is matching not only concerning how you act

(push vs pull, say) but also on which object you act (this switch or that one, say).

On (iii), note that, as Elisabeth has stressed,

motor representations represent not only ways of acting but also objects on which actions

might be performed and some of their features related to possible action outcomes involving

them (for a review see Gallese & Sinigaglia 2011; for discussion see Pacherie 2000, pp.

410-3). For example visually encountering a mug sometimes involves representing features

such as the orientation and shape of its handle in motor terms (Buccino et al. 2009;

Costantini et al. 2010; Cardellicchio et al. 2011; Tucker & Ellis 1998, 2001).