Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Object Indexes

‘the movement performed by object B appears simultaneously under two different guises: (i) as a movement (belonging to object A), (ii) as a change in relative position (by object B)’

Michotte 1946 [1963], p. 136

‘the physical movement of the object struck gives rise to a double representation. This movement appears at one and the same time (a) as a continuation of the previous movement of the motor object, and (b) as a change of relative position (a purely spatial withdrawal) of the projectile in relation to the motor object.’

Michotte 1946 [1963], p. 140

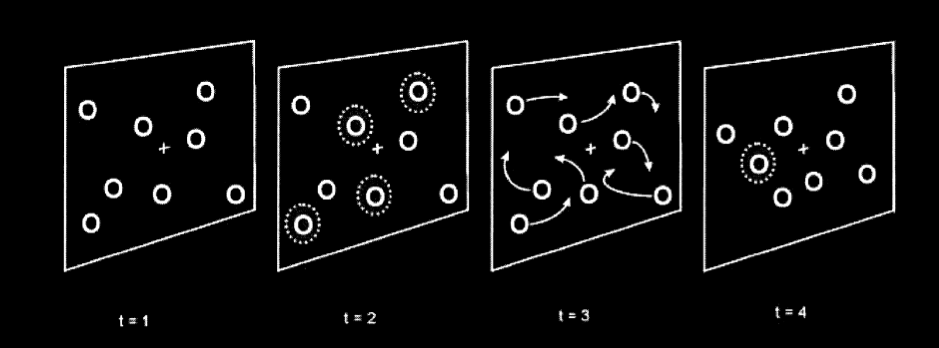

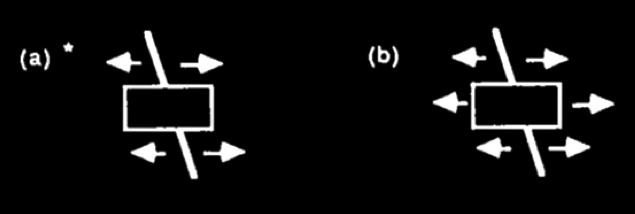

Pylyshyn 2001, figure 6

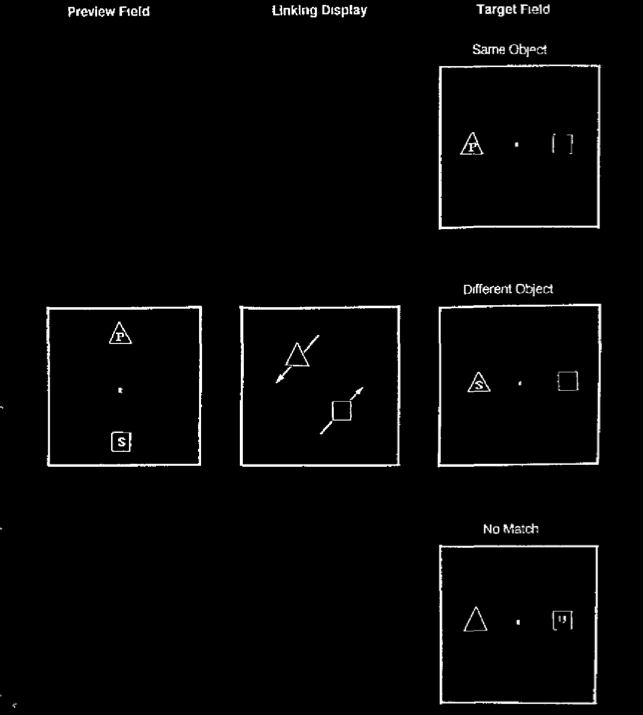

Kahneman et al 1992, figure 3

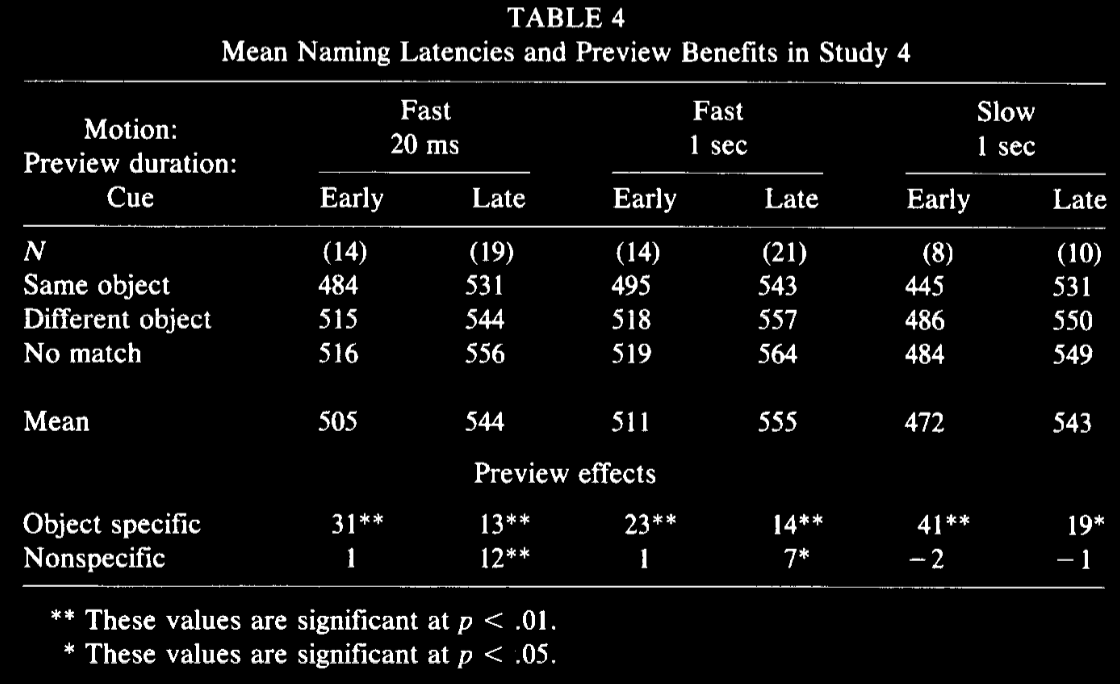

Kahneman et al 1992, table 4

object index / file

Assignments of object indexes can conflict with beliefs and knowledge states.

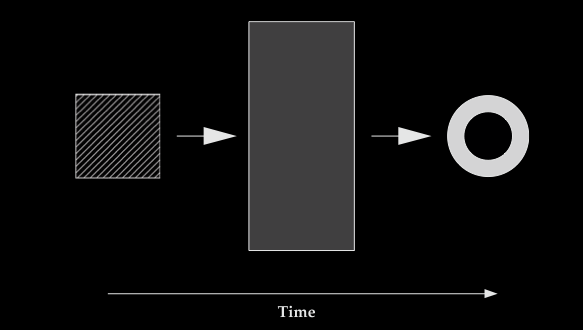

Scholl 2007, figure 4

What principles characterise how object indexes are assigned and maintained?

Spelke, 1990 figure 2a

- cohesion—‘two surface points lie on the same object only if the points are linked by a path of connected surface points’

- rigidity—‘objects are interpreted as moving rigidly if such an interpretation exists’

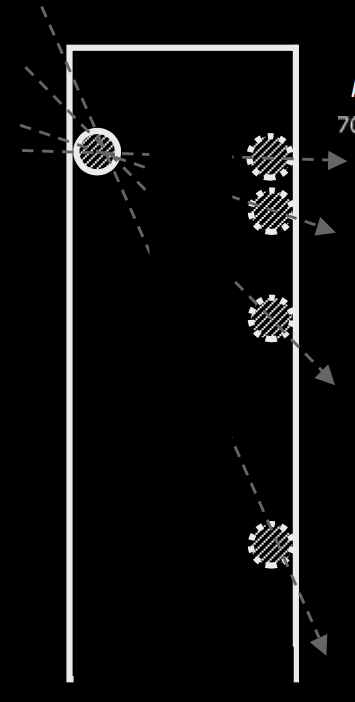

principle of continuity---

an object traces exactly one connected path over space and time

Franconeri et at, 2012 figure 2a (part)