Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Appendix: The Pulfrich Double Pendulum Illusion

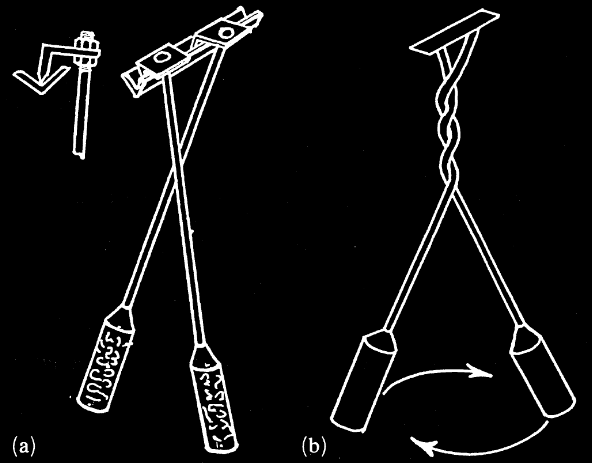

Wilson & Robinson 1986, figure 1

The Pulfrich double pendulum illusion \citep{wilson:1986_impossibly}.

figure caption: ‘The double Pulfrich pendulum: (a) construction of the

pendulums; (b) what observers do not see. The pendulums are set swinging in

opposite phase and observed with both eyes, one eye covered by a neutral

density filter ( ~ 2 log units). Observers see the pendulum bobs following

each other round in a horizontal ellipse. They do not see the arms twist

round each other as they should if the seen movements of the bobs were

veridical. Observers are disconcerted by this inconsistency.’

LESLIE: ‘What Wilson and Robinson do not describe, however, is what observers

see happening to the rods. They say that observers do not see them twisting

round each other, but they do not say what observers do see.’

‘I have therefore investigated this myself ... Equally striking is the clear

perception of the rigid solid rods passing through each other. Most observers

were able to find an angle of view where even the pendulum bottles appear to

pass through one another despite their large size and marked surface texture.’

\citep[pp.~198--9]{Leslie:1988ct}

Note that there is a dearth of information about whether assigning and

maintaining object indexes really does take into account solidity.

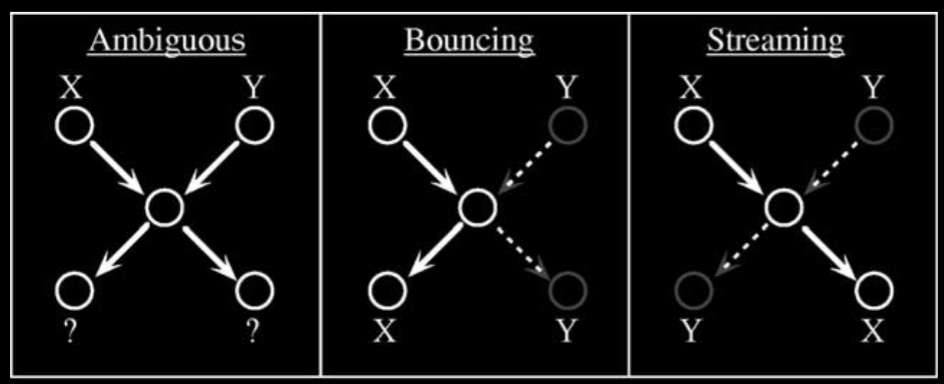

Mitroff, Scholl and Wynn 2005, figure 2

Compare Scholl and Mitroff’s bouncing/streaming study. This study:

(i) suggests solidity may be a constraint, at least sometimes;

(ii) indicates that phenomenology and object indexes may not perfectly align

Mitroff et al p. 74: ‘we induced a strong bias to consciously perceive

streaming, by using smooth, constant, and reasonably fast motion. This

allows us to provide the clearest possible situation in which to evaluate

the relationship between conscious percepts and object files.’

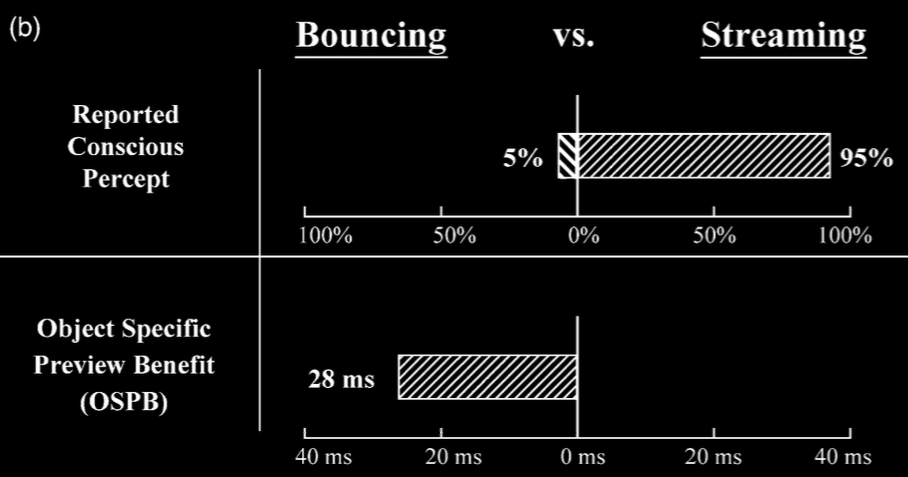

Note that:

The claim that some system of object indexes sometimes gives rise to

phenomenal expectations does not imply that object indexes and phenomenal

expectations are always aligned. Mitroff et al. (2005) construct a situation

involving two objects which simultaneously undergo temporary occlusion. In

this situation, perceivers’ verbal reports imply the objects’ paths crossed

whereas measuring an object-specific preview benefit implies that the objects

bounced off each other. The object indexes underpinning object-specific

preview benefits are unlikely to be informing phenomenal expectations about

objects’ movements in this situation. Object indexes and phenomenal

expectations can come apart in some situations.

Mitroff, Scholl and Wynn 2005, figure 3

Return to the claims and Rips’ objection ...

‘object perception reflects basic constraints on the motions of physical bodies …’

(Spelke 1990: 51)

\citep[p.\ 51]{Spelke:1990jn}

‘A single system of knowledge … appears to underlie object perception and physical reasoning’

\citep[p.\ 175]{Carey:1994bh}

(Carey and Spelke 1994: 175)

I think there's something here that should be uncontroversial, and

something that's more controversial.

Rips’ objection (2011, p. 92)

Leslie’s informal report on the Pulfrich double pendulum illusion (which

appears never to have been published) suffices to show that

it was too simple to say that

‘object perception and causal perception are one and the same process’ or to

talk about ‘object perception and physical reasoning’.

But it remains possible that the launching effects are consequences of the

ways that object indexes are assigned and maintained (although this is far

from the only conclusion compatible with the limited available evidence).

Rips: ‘This possibility, though, is not one that advocates of Michotte’s

hypothesis have taken up. The favored view is one in which separate

modules are responsible for descriptions of objects and of their

mechanical interactions, with central mechanisms then resolving potential

conflicts between them.

For example, Leslie (1988) argues that perceptual

modules do not by themselves settle inconsistencies between the spatial

positions of objects and their causal interactions. In certain

illusions, adults tend to perceive solid objects passing through each other

(Leslie cites the Pulfrich double-pendulum illusion; see Wilson &

Robinson, 1986). Thus, the module for object tracking doesn’t prohibit

interpretations of physical events that are causally impossible. Of

course, people realize that such events cannot really be taking place and

are surprised when they perceive them, but that is because they have

principles stored in long-term memory—for example, the principle that two

solid objects cannot be in the same place at the same time—that classify

these events as illusions or anomalies. Leslie’s argument suggests

that people individuate objects and calculate their causal relations by

means of separate mechanisms; thus, we can’t count on causal constraints

being part of the object-tracking module. If Leslie is right, there is

reason to question Butterfill’s (2009) conjecture that ‘object

perception and causal perception are one and the same process’’ (p.

421).’