Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

A Question about Experiences of (Speech) Actions

What do we experience when we

encounter others’ speech actions?

Indirect Hypothesis vs Direct Hypothesis

What do we experience when we

encounter others’ speech actions?

Indirect Hypothesis vs Direct Hypothesis

?

motor representation -> experience of action -> thought

What do we experience when we encounter others’ (speech) actions?

Indirect Hypothesis vs Direct Hypothesis

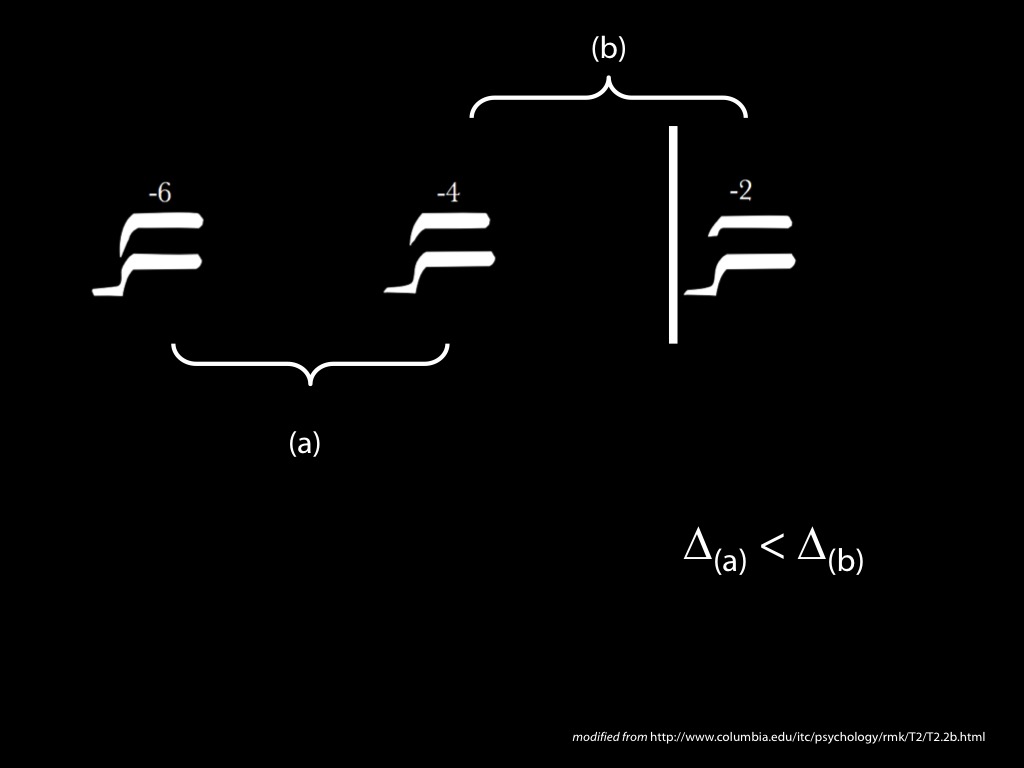

(1) The second sequence of sensory encounters, (b), differ from each other more in phenomenal character than the first sequence of sensory encounters, (a), differ from each other.

(2) This difference in differences in phenomenal character is a fact in need of explanation.

(3) The difference cannot be fully explained by appeal only to perceptual experiences as of acoustic features of the stimuli.

(4) The difference can be explained in terms of perceptual experiences as of phonetic properties.

(5) There is no better explanation of the difference.

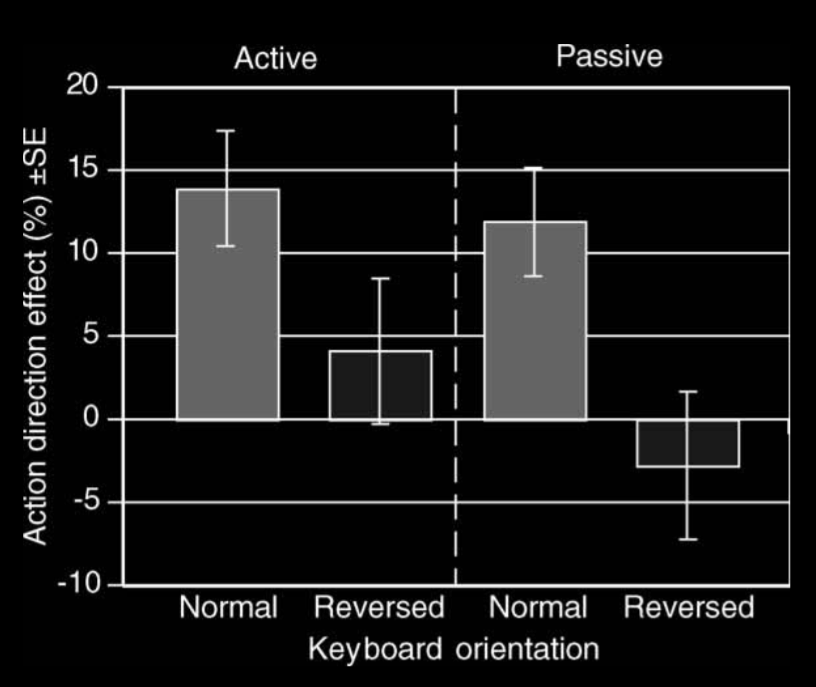

motor processes affect acoustic expeirences

Repp & Knoblich 2009, figure 3

motor processes affect acoustic expeirences

(1) The second sequence of sensory encounters, (b), differ from each other more in phenomenal character than the first sequence of sensory encounters, (a), differ from each other.

(2) This difference in differences in phenomenal character is a fact in need of explanation.

(3) The difference cannot be fully explained by appeal only to perceptual experiences as of acoustic features of the stimuli.

(4) The difference can be explained in terms of perceptual experiences as of phonetic properties.

(5) There is no better explanation of the difference.

What do we experience when we encounter others’ (speech) actions?

Indirect Hypothesis vs Direct Hypothesis