Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Signature Limits

Q1

How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing models?

Q2

Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

Q3

Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes but not always automatic? How could belief-tracking be automatic given evidence that it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?

How can we test

which model of the mental physical

a process is using?

Using signature limits!

signature limits

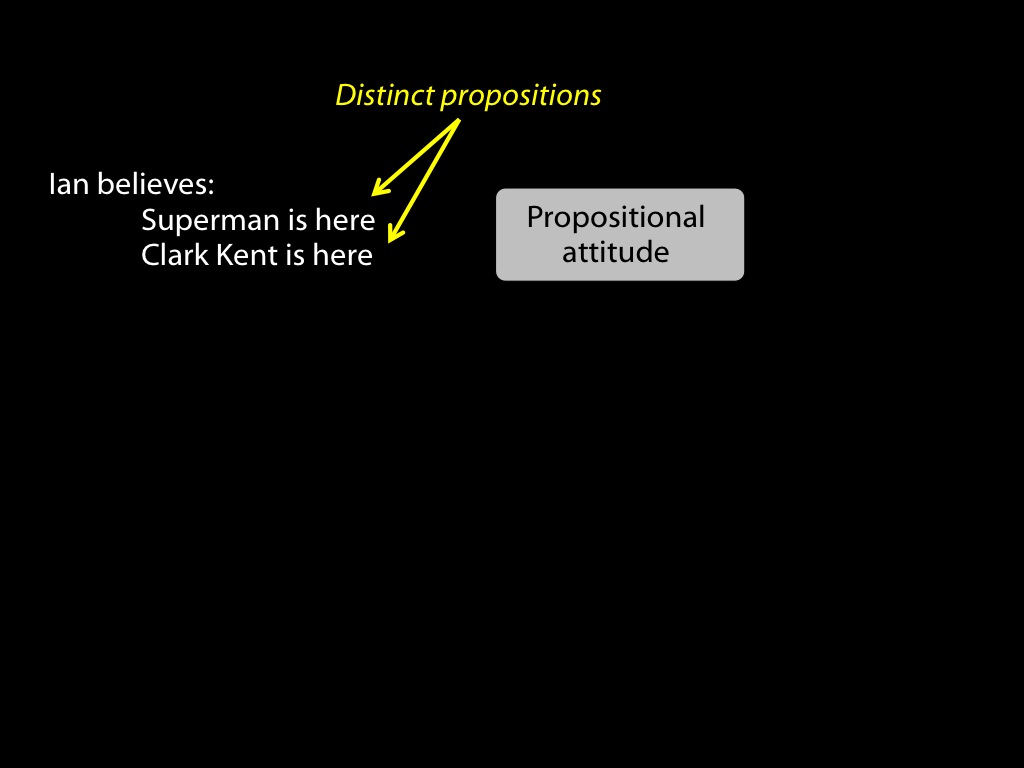

Hypothesis 1

Response R is the product of a process using a model characterised by Theory 1

Fact

Theory 1 predicts that the protagonist will J.

Prediction of Hypothesis 1

Response R will proceed as if the protagonist will J.

Hypothesis 2

Response R is the product of a process using a model characterised by Theory 2

Fact

Theory 2 predicts that the protagonist will not J.

Prediction of Hypothesis 2

Response R will proceed as if the protagonist will not J

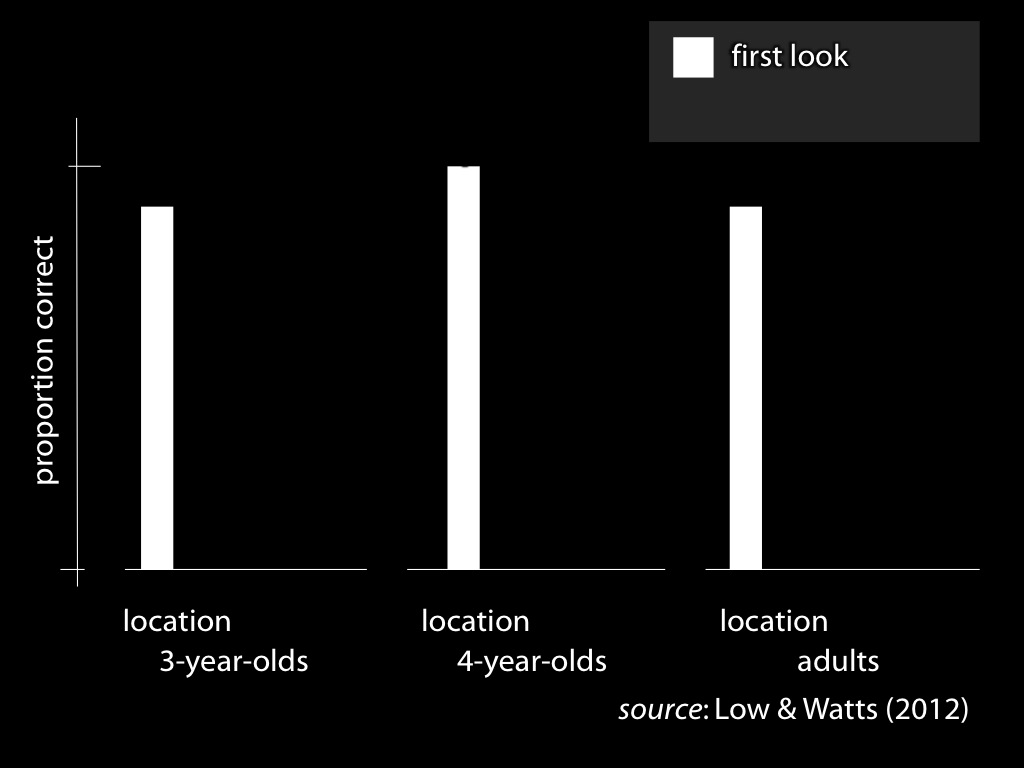

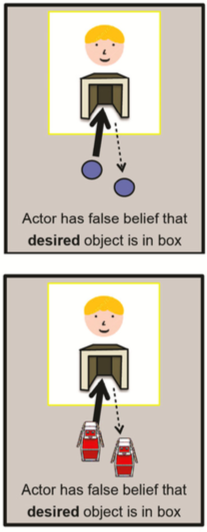

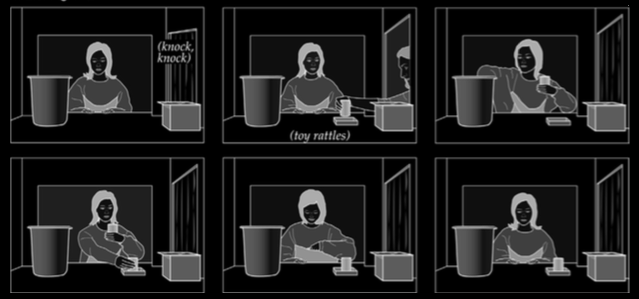

While the protagonist is present, the item is placed in Location-1.

The protagonist [ stays / leaves ],

and the item is [ moved / transformed ].

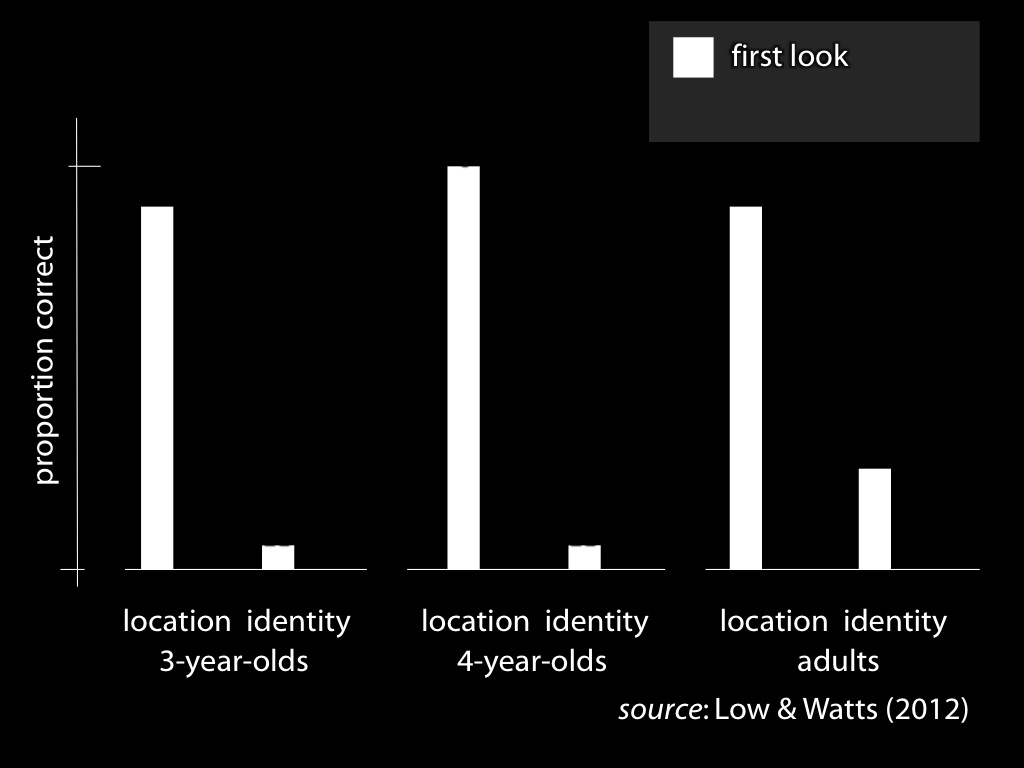

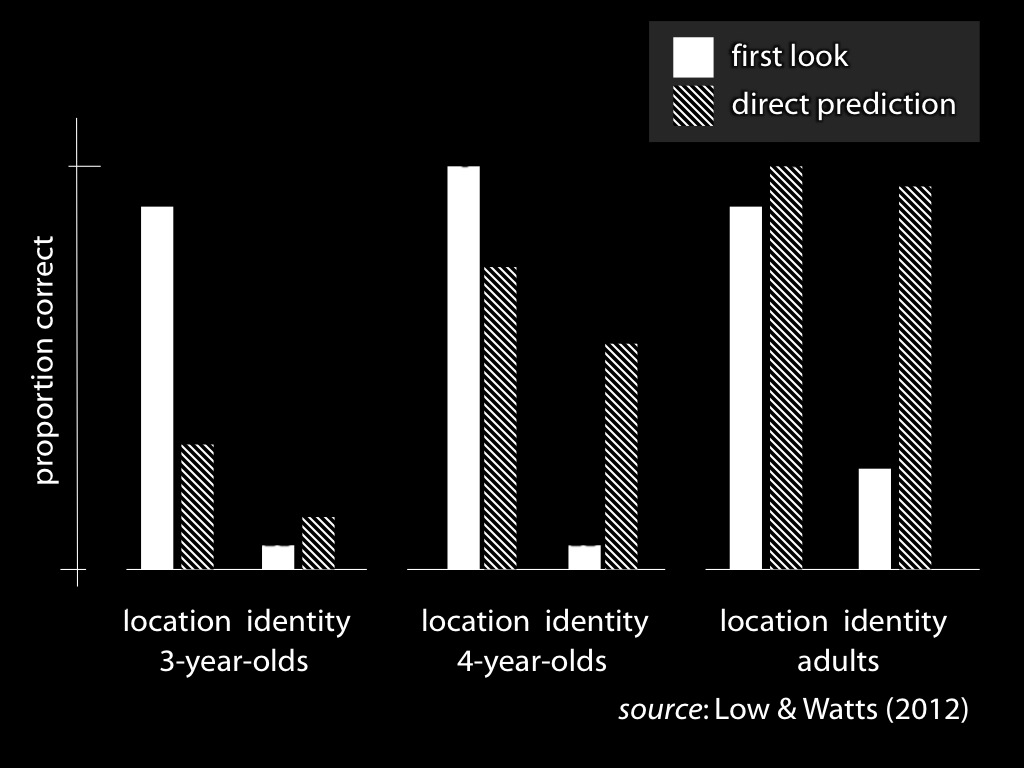

drawn from Low & Watts (2013); Low et al (2014)

drawn from Low & Watts (2013); Low et al (2014)

drawn from Low & Watts (2013); Low et al (2014)

Q1

How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing models?

Q2

Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

Q3

Why is belief-tracking in adults sometimes but not always automatic? How could belief-tracking be automatic given evidence that it significantly depends on working memory and consumes attention?

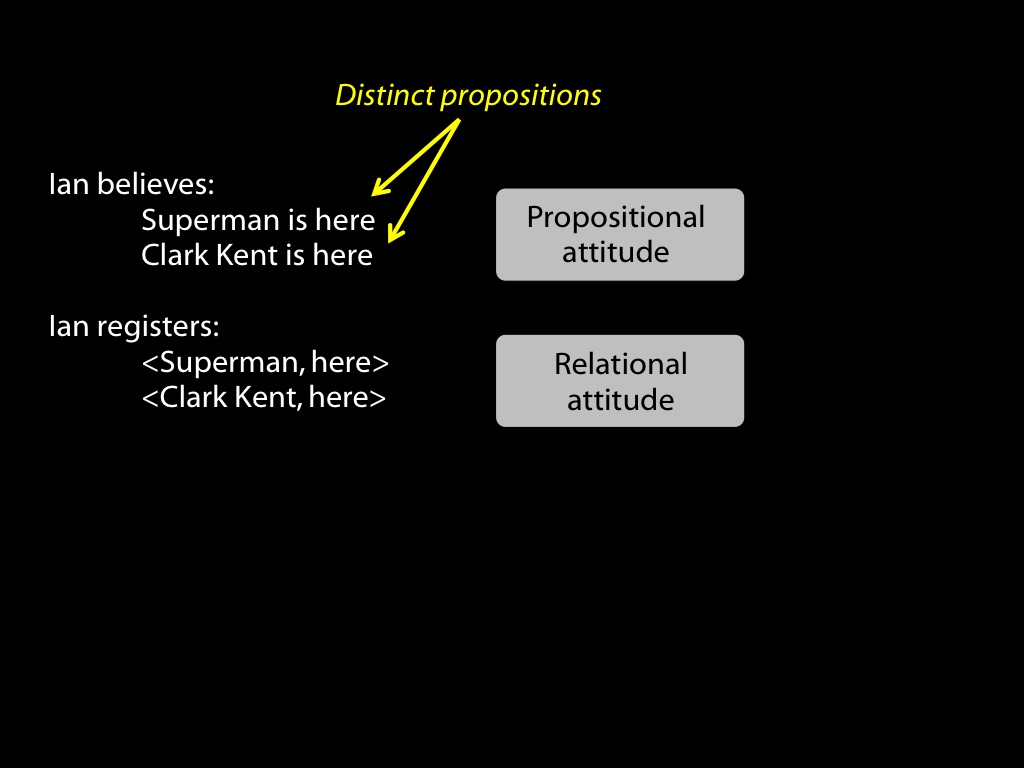

Requirement 1: Diversity in strategies

Requirement 2: Models

signature limits

of minimal models of mind

- identity as compression/expansion [has been tested*]

- duck/rabbit [has been tested*]

- fission/fusion [is being tested*]

- quantification

measures:

- spontaneous anticipatory looking

- looking duration

- active helping (Fizke et al, 2017; unpublished data)

- response times

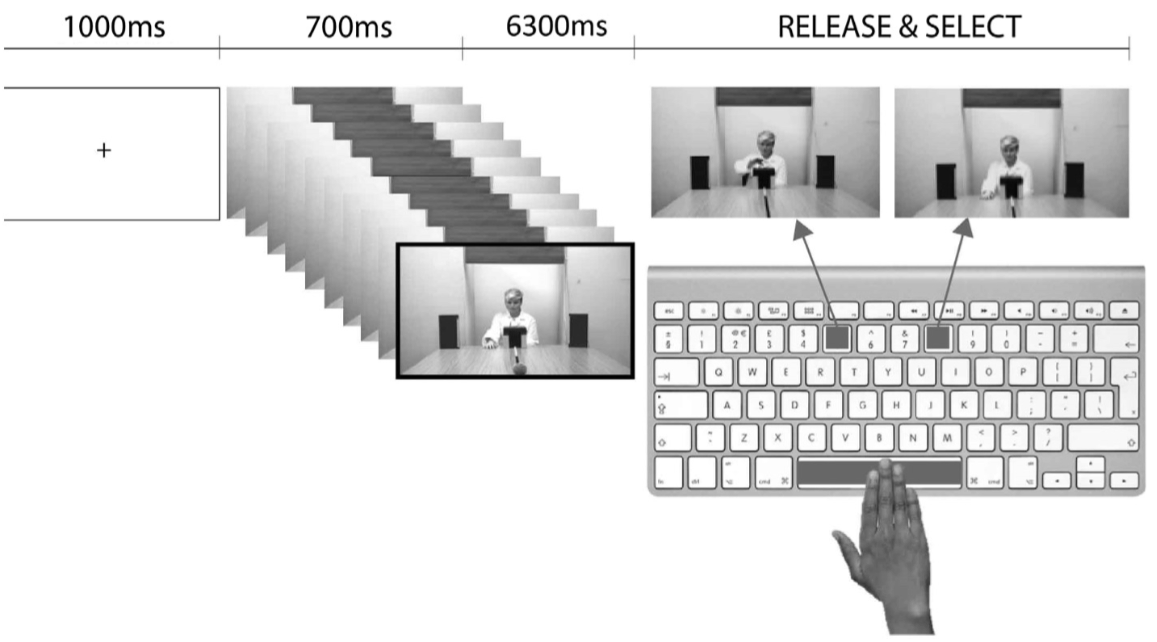

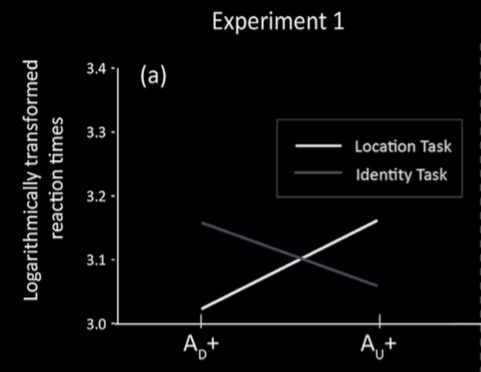

Edwards and Low, 2017 figure 7a

Edwards and Low, 2017 figure 7a

Edwards and Low, 2017 figure 7a

categorical vs non-categorical measures

‘The test for a significant [...] effect is concerned only with the question of whether a true difference in response times (RTs) exists in the population, regardless of its size.

‘One can conclude from this effect only that some classification of the [actions] has happened, but [...] whether it was more [or less] accurate than in the direct task remain unknown.

To make the claim that the RTs are evidence for good [or bad] unconscious classification, [we] would have needed to show that the RTs can be used to [predict the actions].’

Franz and von Luxburg, 2015 p. 1646

Scott et al (2015, figure 2b)

Constructing minimal theories of mind yields models of the mental which

... could be used by automatic mindreading processes.

... are used by some automatic mindreading processes.

... are the only models used by automatic mindreading processes.

Automaticity requires (some degree of) cognitive efficiency,

but using a canonical model is cognitively demanding.

- working memory

- attention

- inhibitory control

- it makes people slow down